A rally at the South Carolina Statehouse for the removal of the Confederate flag, with the banner waving in the background. (photo by maracgay/Instagram)

Yesterday afternoon, South Carolina Governor Nikki Haley called for the removal of the Confederate flag from the grounds of the state capitol. The flag that, perhaps more than any other symbol today, represents the system of black slavery and white supremacy upon which this country was built — and which, interestingly, was never the official flag of the Confederacy — has flown over the grounds of the South Carolina State House in Columbia since 1962. It was waving in the wind long before white 21-year-old Dylann Roof allegedly murdered nine black people at Charleston’s Mother Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church on June 17; it was waving at full mast the day after, when the other flags on the grounds were lowered to half; and it waves still.

Haley’s call for the removal of the flag is certainly a step in the right direction, but as Jelani Cobb pointed out, writing for The New Yorker:

The State House flag itself is, on the whole, less than impressive. Tethered to a thirty-foot pole protected by an iron enclosure, the red-and-blue swath of fabric is actually fairly easy to miss. Less easily overlooked, however, is the massive memorial to Benjamin Tillman, the former governor and avowed Negrophobe who spoke proudly of having led lynching parties in his youth. When I spoke to [Tom] Hall, the attorney and filmmaker, after the rally, he pointed out something that few critics of the flag have observed. “It’s not just the flag. The entire Capitol grounds are basically a tribute to white supremacy.” Sixty feet beyond the monument to Tillman is a memorial for J. Marion Sims, the pioneering gynecologist who perfected his craft by performing experimental surgeries on enslaved black women. “The only black person whose name appears anywhere on these grounds is Essie Mae Thurmond — the illegitimate black daughter of Senator Strom Thurmond,” Hall said. The flag is not the only symbol valorizing the racially horrific past, or even the most visible; it is simply the most obvious.

In other words — and as countless others have pointed out by now — the Columbia flag is a small piece of an enormous iceberg: the legacy of the Confederacy memorialized and on full display throughout the American South.

The Mississippi state flag incorporates the image of the Confederate flag in the top left corner. (image via Wikipedia)

It’s hard to know where to even begin. With other Confederate flags? Well, Mississippi’s state flag incorporates it. The design of Georgia’s state flag is based on the first official flag of the Confederacy. Other state banners are connected to the Confederacy in more or less obvious ways. The Confederate flag is featured on custom license plates, and needless to say, plenty of people hang or fly it on private property, such as “a huge Confederate flag planted on a 90-foot pole along I-95 north of Fredericksburg” in Virginia. Frighteningly, its popularity isn’t even limited to the United States.

The towering Robert E. Lee Monument in New Orleans (photo by Ken Lund/Flickr) (click to enlarge)

Then there are the monuments — hundreds of them. Wikipedia’s “list of monuments and memorials of the Confederate States of America” includes more than 50 such statues in Arkansas alone (by far the state with the most). And that list is far from complete, because Louisiana isn’t on it — a state whose largest city, New Orleans, has a traffic circle devoted to Robert E. Lee. Towering over the circle is a 12-foot statue of the Confederate general atop a 60-foot column (the whole thing included on the National Register of Historic Places). The cruel irony of this is presumably not lost on the city’s majority black population, nor on discerning outsiders: for his work “Silent parade… or the Soul Rebels Band Vs. Robert E. Lee,” artist William Cordova enlisted members of the Soul Rebels brass band to stand atop a nearby building and blast their music at the general. Lee’s monolith is just one of “many monuments to the Confederacy” strewn throughout a city that lacks a single memorial for soldiers who fought on the side of the Union, according to Jarvis DeBerry writing on NOLA.com.

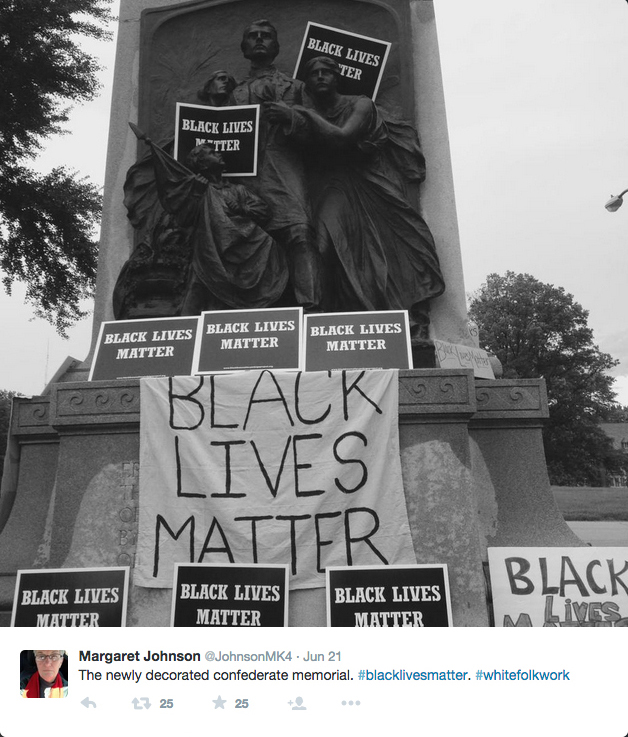

In the week since Roof committed his act of racial terror, activists have begun to take notice of these monuments and intervene. In Baltimore, Charleston, Austin, and no doubt elsewhere, protesters have been painting the phrase “Black Lives Matter” on the base of statues devoted to Confederate fighters. In St. Louis, activists covered a 32-foot-tall Confederate Memorial in “Black Lives Matter” signs and banners, reactivating discussion of a monument that’s been the subject of controversy for over a century.

(via PhillipDWeiss/Twitter)

(via cskea93/Twitter)

(via JohnsonMK4/Twitter)

A St. Louis Magazine story quotes both an activist and a historic preservationist as saying they have mixed feelings about the potential removal of the memorial; they cite the positive way in which it could be used to educate and spark discussion. And indeed, if further proof were needed to demonstrate how deeply entrenched racism and white supremacy are in this country, the littering of monuments to the Confederacy and Confederate soldiers and generals throughout the US is certainly instructive. Then again, so is the premeditated murder of nine black people by someone who said he wanted to “start a race war.”

Memorials are how we recount and publicly value our history (although how we tell that history is often distorted by political correctness and who can afford to build them). Dismantling all of these Confederate monuments and simply pretending nothing ever happened — continues to happen — would serve no one. But could we stand to remove some, replacing them instead with monuments to slave rebellions, to black leaders, perhaps an official Tomb of the Unknown Slave? In doing so, could we try in some small way to rebalance the story of this country? Emphatically, yes.

Of course, it’s important not to overstate the power of such symbols — not to confuse the removal of a flag with real policy changes that could positively affect the lives of African Americans. Taking down the flag in Columbia “offers a kind of equality — an equality of emptiness — to black South Carolinians,” Cobb writes. Still, allowing black Americans to drive their cars or ride the bus to work without having to pass a hovering, hallowed symbol of slavery on the way wouldn’t be a terrible place to start.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου