1) The Varangian question –

The Eastern Roman Empire was still the richest political entity of Europe in the middle ages, and as such its capital of Constantinople tended to attract invaders (in search of plunder) and mercenaries (in search of pay) alike. And as such, the warriors and adventurers of Rus were also enthralled by its riches. Now Rus in itself pertained to a loose federation of Slavic trading towns and villages spread across Russian and Ukraine, and these settlements were ruled by an originally Swedish elite (Vikings from Scandinavia), who had later mixed with the local populace. In any case, bands of these roving fighters gradually started to gravitate towards Constantinople (the Rus called it Miklagard – ‘City of Michael’), some for raiding purposes and others for trading. And by late 9th century AD, the Eastern Roman sources referred to them as the Varangians.

Interestingly, the very term Varangian (Old Norse: Væringjar; Greek: Βάραγγοι, or Varangoi) is open for etymological debate. Though most scholars tend to agree that it is derived from Old Norse væringi, which is a compound of vár ‘pledge or vow of fidelity’ and gengi ‘companion or fellowship’. Simply put, the term Varangian can be roughly translated to ‘sworn companion’ – which proved to be an apt categorization, as later history was witness to their glorious feats.

2) Forged by the civil war of the ‘Greeks’ –

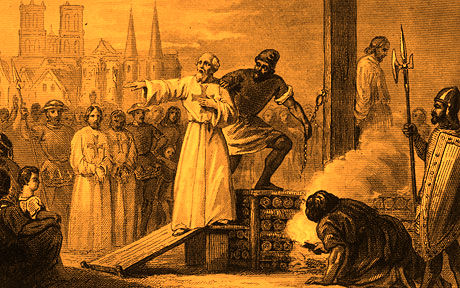

Basil II flanked by his royal guards.

However on entering the service of Basil II, the group proved its mettle in various encounters, thus ultimately allowing the emperor the crush the rebel army and its commanders. On the political side of affairs, there was another significant development – Vladimir the Great converted to Orthodox Christianity (the state religion of Eastern Roman Empire) and even married Princess Anna of Byzantine. This paved the way for further ‘supply’ of warriors from Rus. So by the end of the 10th century (and beginning of 11th century), Basil II wholeheartedly made use of his ‘Varangians’, and successfully campaigned far and wide, ranging from Levant to Georgia. These success ratios tempered the ‘foreign’ Rus warriors into a disciplined body of troops who formed the core of the imperial guard. And so the famed Varangian Guard was forged – symbolizing the might of the Eastern Roman emperor himself.

3) Upholding the contrasting statuses of both mercenaries and royal guards –

Employing mercenaries was a trademark of Eastern Roman military stratagem even in the earlier centuries. But the recruitment of the Varangians (by Basil II) was certainly different in scope, simply because of the loyalty factor. In essence, the Varangians were specifically employed to be directly loyal to their paymaster – the Emperor. In that regard, unlike most other mercenaries, they were dedicated, incredibly well trained, furnished with the best of armors, and most importantly devoted to their lord. This sense of loyalty was manifested many times in the course of history, with one particular incident involving the great Alexios Komnenos. After revolting, Komnenos appeared before the gates of Constantinople with his superior army, while the capital itself was defended only by some imperial soldiers, including the Varangian Guard and a few other mercenaries. But in spite of their precarious situation, the Varangians stayed faithful to Emperor Nikephoros III Botaneiates till the last moment, before the ruler himself abdicated in favor of a bloodless coup. Suffice it to say, the guard was retained after Komnenos came to power.

On the other hand, it begs the question – then why was the Varangian Guard still branded as a mere mercenary group? Well the answer relates to practicality of court politics. Unlike other imperial guard regiments, the Varangian Guard was (mostly) not subject to political and courtly intrigues; nor were they influenced by the provincial elites and the common citizens. Furthermore, given their direct command under the Emperor, the ‘mercenary’ Varangians actively took part in various encounters around the empire – thus making them an effective crack military unit, as opposed to just serving ceremonial offices of the royal guards.

4) The Anglo-Saxon connection –

As we mentioned before, the Varangian Guard was initially formed mostly of warriors and adventurers from Rus who tended to have Swedish lineage. However by late 11th century, these ‘Scandinavians’ were gradually replaced by the Anglo-Saxons from Britain. There was a socio-political side to this ambit, since most of England was overrun by the Normans under William the Conqueror (post 1066 AD). As a result, the native Anglo-Saxon military elites of these lands had to look for opportunities elsewhere – thus kick-starting mini waves of migration from Britain to Black Sea coasts, and then ultimately to Eastern Roman Empire. Interestingly enough, many Byzantine commanders welcomed these refugees from the British Isles, with some even concocting propaganda measures that proclaimed the arrival of the ‘English’ Anglo-Saxons as being equal to the fealty of the Romano-British soldiers of ancient times (when Britain was a Roman province).

In fact, there are contemporary sources that talk about how English was actually spoken in the streets of Constantinople, thus alluding to the presence of many Anglo-Saxons mercenaries. And almost like a poetic justice, just fifteen years after the Battle of Hastings (where the Anglo-Saxons were decisively defeated by the Normans in 1066 AD), a group of ‘English’ veterans got the chance for a payback. This time around they formed the core body of the Varangian Guard (under Alexios Komnenos), while being pitted against the Normans from southern Italy (under Robert Guiscard). Unfortunately for the Anglo-Saxons, they were to too eager to challenge their enemy – and so by breaking their formation, the Varangians charged into the right wing of the Normans. Their initial impact was devastating to Guiscard’s army. But once the tide was stemmed, the Anglo-Saxons were surrounded and woefully outnumbered. Afflicted by weariness and their heavy armor, the group was mostly destroyed in a piecemeal manner by Norman counter-charging.

5) Ethnicity and the numbers game –

We have already talked about how the early members of the Varangian Guard mostly hailed from Rus, while by late 11th century they were gradually superseded by the Anglo-Saxons. But that doesn’t necessarily mean that the guard was exclusively composed of these two groups. In fact, from the initial times, the Swedish Varangians were often accompanied by their Norwegian brethren who arrived directly from Scandinavia (as opposed to Russia). Similarly, by 11th century, the Danes also arrived on Byzantine shores, along with the Anglo-Saxons. Moreover, according to contemporary sources (like that of Leo of Ostia), there are references to the ‘Gualani’ people serving in the Varangian Guard. Historians are not sure about their origins, with hypotheses identifying ‘Gualani’ as Welsh peoples and in some cases as the Vlachs (of Eastern Europe).

Beyond the melting pot of different nationalities, there is always the question of the actual numbers that were present in the Varangian Guard. During Basil II’s time, the figure was kept at more or less at 6,000 men. But the numbers, in accordance to sources, kept fluctuating after 11th century – though most of them dealt with the Varangians participating in battles, and these warriors were possibly only a part of the entire Varangian Guard in its full capacity. In any case, the figures range from 4,500 men to a paltry 540 men. By late 13th century AD, the numbers were (probably) officially dropped to 3,000 men. By then the Varangian Guard formed one-half of the Taxis (the core army of the Empire of Nicaea), while the other-half was formed by the Vardariotai, who were originally of Magyar (Hungarian) origin.

6) Mixed tactics and the Pelekys ax –

With so much talk about the Varangian Guard taking the fields – as mentioned in so many literary sources, there is surprisingly little knowledge about how they actually functioned in the battles in regard to tactics. Now given their penchant for wielding axes and wearing heavy armor, it can be credibly surmised that the Varangian Guard operated as an infantry formation in defensive positions by the emperor’s side. However there were instances when the Varangians were arrayed at the front of the army, while being backed by the Vardariotai, who operated as experienced horse archers during Alexios Komnenos’ time. In essence, this contrasting composition provided the nigh perfect tactical scope of shock and missile units. But there were also scenarios when the Varangian Guard was deployed at the back to protect the precious baggage train, while they supported other heavy infantry formations of the Eastern Roman army. Simply put, such changing positions on the field possibly mirrored the adaptable ‘mixed’ tactics preferred by the Varangians – thus confirming their elite military status. In that regard, it was almost customary to allow the Varangians to take the first plunders from a conquered settlement.

In any case, the popular imagery of a Varangian guardsman generally reverts to a tall, heavily armored man bearing a huge ax rested on his shoulder. This imposing ax in question entailed the so-called Pelekys, a deadly two-handed weapon with a long shaft that was akin to the famed Danish ax. To that end, the Varangians were often referred to as the pelekyphoroi in medieval Greek. Now interestingly, while the earlier Pelekys tended to have crescent-shaped heads, the shape varied in later designs, thus alluding to the more ‘personalized’ styles preferred by the guard members. As for its size, the sturdy battle-ax often reached to an impressive length of 140 cm (55-inch) – with a heavy head of 18 cm (7-inch) length and blade-width of 17 cm (6.7-inch).

7) Countering piracy and policing streets –

With their Viking heritage and Rus tradition of distant seafaring, it was expected of the Varangians to have maritime skills. So beyond battlefield maneuvers and palace duties, some of the younger (or less experienced) members of the Varangian Guard were chosen to actually hunt down pirates. These guardsmen were deployed in specially-made light marine crafts called the ousiai, and they worked in unison with the other Nordic and Russian mercenaries.

But other than glorious feats in battles and adventurous sea-raids, the Varangian Guard was also involved in slightly more mundane duties, like policing the streets of Constantinople. They rather carved up a brutal reputation for themselves – who were known to enforce strict laws and arrest the political opponents of the emperor. And as an extension of their perceived ferocity and penchant for violence, few Varangians were also employed as jailers because of their ‘specialization’ in torturing techniques. Interestingly, Georgius Pachymeres, a 13th century Greek historian and philosopher, talked about one such chief (epistates) of the prison guards, whose moniker was Erres ek Englinon or ‘Harry from England’.

8) The Emperor’s Wineskins –

Now while we mentioned before how the Varangians were employed as rigorous law enforcers in the capital, they themselves were not too reluctant to break certain laws of decorum. One of the reasons for their boisterous nature was possibly due to their notable love for Greek wine. Often derogatorily called the “Emperor’s wineskins”, their absurd levels of drunkenness often landed the guards into trouble – with two particular incidents even involving drunken guardsmen assaulting their own emperor. And beyond obsession for alcohol (that sometimes turned into abuse), the Varangians were also known for their fascination for visiting brothels, along with the fancy for other ‘Greek’ stuff, like Hippodrome races and spectacles.

9) High fee for entry into the Guard –

Now given their status as the elite members of the imperial guard, the Varangians were obviously paid very highly. However in an odd arrangement, only affluent members were inducted into the guard. The threshold was maintained by a relatively high fee (in gold) that the would-be inductee had to pay the Roman authorities in order to be considered for the role of a Varangian guardsman. And after passing this monetary ‘test’, the applicant was further examined and evaluated, so as to maintain the quality and discipline of the Varangian Guard. In any case, it should be noted that in most situations, the Varangians on being accepted, acquired far more riches (from compensations, bonuses and spoils) than their initial fee of entry. So from a realistic perspective, there was no dearth of applicants – with even the rejected ones making names for themselves in the other (albeit less renowned) mercenary companies of the Eastern Roman empire.

10) Harald Hardrada of the Varangian Guard

In our previous entry, we talked about how the applicant needed to provide a lump-sum amount of gold to be considered for the Varangian Guard. This seemingly unique measure allowed many rich adventurers, princes and even warlords from northern Europe to take their (and their retinue’s) chance to be inducted in this elite mercenary group. One such adventurer was the great Harald Hardrada. In his teenage years, he had to escape from his native Norway after ending up in a losing battle. The young man made his way to Kievan Rus, and made a name of himself on various military encounters, by fighting for the Grand Prince Yaroslav the Wise. But after rising to the rank of a military captain, young Harald took a gamble and made his way to Constantinople, along with 500 of his personal followers. Fortunately for the group, most of them were selected for the Varangian Guard, and thus started Harald’s incredible journey to redemption.

The ‘Viking’ once again proved his worth, and fought in various successful assignments in Sicily against both the Muslims and the Normans. According to his skald Þjóðólfr Arnórsson, many conflicts took the still young Harald even to Asia Minor and Iraq, where he had successfully fought off Arab pirates. After reportedly capturing around eighty Arab strongholds, the Scandinavian even made his way to Jerusalem, to probably oversee a peace agreement made between the Eastern Roman Empire and the Fatimid Caliphate in 1036 AD. However it was in 1041 AD when the Viking arguably played his most crucial role as a Varangian – by ruthlessly putting down a Bulgarian uprising led by Peter Delyan – which supposedly gained Harald the nickname of “Devastator of the Bulgarians” (Bolgara brennir).

In the latter years, he acquired much wealth and prestige throughout the Roman realm. But in spite of his status as an elite guardsman (possibly holding the rank of Manglabites), he planned to leave Constantinople for Rus, probably because of an ill-favored political climate in the capital. In Rus he married a Russian princess, elevated his status to a Prince, and then triumphantly made a return to his homeland Norway. In the years between 1046 – 1065 AD, Harald was finally able to gain the kingship of Norway through various political and military machinations (maneuvers that were undoubtedly learned during his time in the Eastern Roman court). And ultimately in 1066 AD, the King of Norway – Harald Hardrada, launched the last ‘Viking’ invasion of England; thereby crippling the local Anglo-Saxon resistance, and thus paving the way for the Norman conquest of Britain. And oddly enough, pushing forth the historical cycle, many of the dispossessed Anglo-Saxons of England in turn went on to become members of the Varangian Guard in the latter years.

Now while this unique episode serves as a rather extreme example, it does provide some insights into the lives of the Varangian Guardsmen – where the wondrous scope of adventures and actions overshadowed any semblance of normalcy expected from a well-paid, ‘governmental’ military career.

Honorable mention – the Varangian Bra

The trademark of the Varangian Guard pertained to carrying an imposing ax and wearing of heavy armor (though in rare cases, they were also lightly armed). Relating to the latter, the armor often entailed ringmail shirts that were sometimes reinforced with lamellar (klivanion) or scale armor. The unwieldy hauberk (mail shirt) weighed around a significant 30 lbs, and so the guardsmen adopted a type of chest harness known as the Varangian Bra. Usually made of leather, the harness consisted of a breast strap with two shoulder straps going over each shoulder, which connected the front and rear end of the strap. Possibly inspired by their ‘eternal’ foes – the Sassanid Persians, the Eastern Romans adopted this peculiar armor (along with buckled belts) as a solution for holding the bulky mail shirt together, which in turn allowed for better mobility on the battlefield.

Sources: De Re Militari / AngelFire / HistoryBits / WeaponsandWarfare

Book References: The Varangian Guard: 988-1453 (By Raffaele D’Amato) / The Varangians of Byzantium (By Sigfús Blöndal and Benedict Benedikz)

Ο

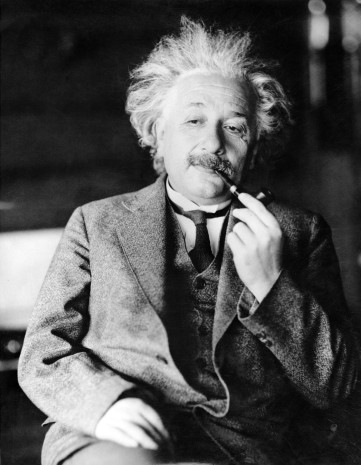

Άλμπερτ Αϊνστάιν ίσως είναι ο μεγαλύτερος επιστήμονας που γνώρισε ποτέ ο

κόσμος. Βραβευμένος με Νόμπελ και εμπνευστής της θεωρίας της

σχετικότητας πέθανε ακριβώς πριν από 60 χρόνια στις 18 Απριλίου του 1955

σε ηλικία 76 ετών αφού πρώτα έθεσε τις βάσεις της μοντέρνας φυσικής και

αφού άλλαξε την οπτική που είχαμε για το διάστημα, τον χρόνο, την

ενέργεια. Όμως πόσοι ξέρουν ότι ήταν εθισμένος στα τηγανιτά αυγά;

Ο

Άλμπερτ Αϊνστάιν ίσως είναι ο μεγαλύτερος επιστήμονας που γνώρισε ποτέ ο

κόσμος. Βραβευμένος με Νόμπελ και εμπνευστής της θεωρίας της

σχετικότητας πέθανε ακριβώς πριν από 60 χρόνια στις 18 Απριλίου του 1955

σε ηλικία 76 ετών αφού πρώτα έθεσε τις βάσεις της μοντέρνας φυσικής και

αφού άλλαξε την οπτική που είχαμε για το διάστημα, τον χρόνο, την

ενέργεια. Όμως πόσοι ξέρουν ότι ήταν εθισμένος στα τηγανιτά αυγά;