s

s

s

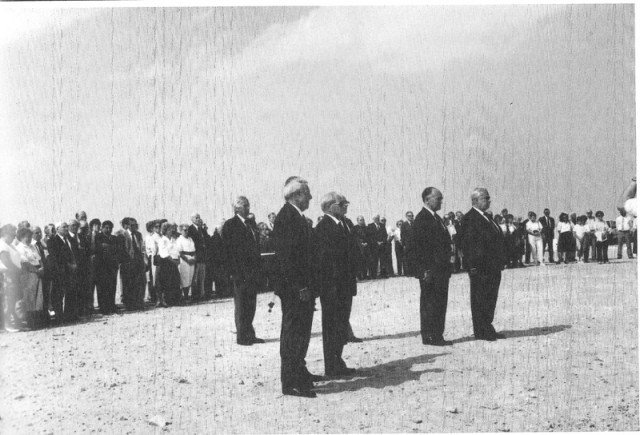

Hans Joachim Marseille, a young German fighter pilot, was the most amazing, unique, and lethal ace of World War 2. A non-conformist and brilliant innovator, he developed his own personal training program and combat tactics and achieved amazing results, including 17 victories in one day, and an average lethality ratio of just 15 gun rounds per victory. Marseille was described by Adolf Galland, the most senior German ace, with these words: “He was the unrivaled virtuoso among the fighter pilots of World War 2. His achievements were previously considered impossible.”

Marseille,

who later became one of the ten most highly decorated German pilots of

World War 2 and was nicknamed “The Star of Africa” by the German

propaganda, (“Jochen” by his friends), had a very unpromising and

problematic start. At age 20 he graduated the Luftwaffe’s fighter pilot

school just in time to participate in the Battle Of Britain in the

summer of 1940. He initially served in fighter wing 52 under Johannes

Steinhoff (176 victories). In his third combat sortie, he shot down a

Spitfire and by the end of the Battle Of Britain he had seven victories,

but he was also shot down four times, and his behavior on the ground

got him into trouble.

A charming person, he had such busy nightlife that sometimes he was too tired to be allowed to fly the next morning. He also loved American Jazz music, which was very politically incorrect in the Nazi military. As a result, he was transferred to another unit as a punishment for “Insubordination”. His new unit, fighter wing 27, was relocated in April 1941 to the hot desert of North Africa, where he quickly achieved two more victories but was also shot down again and still had disciplinary problems.

Luckily

for him, his new Wing Commander, Eduard Neumann, recognized that there

might be a hidden potential in the unusual young pilot and helped him

get on the right track. With his problems on the ground finally over,

Marseille began to analyze deeply his combat activity and started to

improve his abilities as a fighter pilot with an intense self-training

program, both physical and professional, which he developed for himself.

Marseille claimed his 7th aerial victory on 28 September 1940 but had to crash land near Théville due to engine failure.

G-Force – Marseille worked endlessly to strengthen his abdominal and leg muscles to enhance his ability to sustain higher G-Force and for longer durations during dogfights better than the average fighter pilot. G-Force is the enormous centrifugal force experienced when a fighter aircraft makes sharp turns during a dogfight. The modern G-suit that helps pilots sustain it was not yet invented in World War 2.

Aerobatics – Marseille used every opportunity to perform breathtaking aerobatics. In addition to free entertainment to his friends on the ground, this also gave him an outstanding control and confidence in extremely maneuvering his Messerschmitt 109 aircraft.

Marksmanship –

Marseille spent his unused ammunition practicing firing at ground

objects and trained a lot not just in plain strafing but also in high

deflection shooting while in a sharp turn, which is much harder.

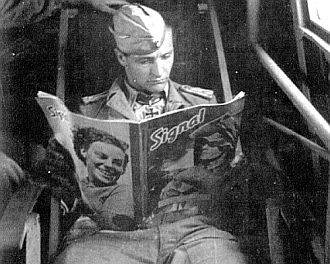

Intelligence – he began to read every possible intelligence information he could find to maximize his knowledge and understanding of the enemy.

Tactics – That’s where Marseille marked himself as a great innovator of air warfare, and he kept improving. He claimed that in the perfect visual conditions over the desert, large formations are in a visual disadvantage against highly maneuvering single aircraft. He preferred to fight alone, with a single wingman providing warnings from a safe distance. He claimed that when fighting alone in a short-range dogfight, he could quickly fire at anything he saw while the attacked formation’s pilots were confused, hesitated, and switched to a defensive position that further increased the lone attacker’s chances.

He also claimed that fighting alone eliminates the high risk of firing at or colliding with a wingman in such extreme maneuvering. Marseille said that in such conditions, there’s a lower chance and too little time for the usual chase attack method, and preferred to use high angle deflection firing from short range while making a sharp turn. In doing so, he never used his gun sight and instead fired a very short burst at the passing target in the split second when its leading edge, its propeller, disappeared from his eyes behind his aircraft’s nose.

He calculated that when firing a short burst at this position, his gun rounds will hit the target’s engine and cockpit, and he trained in this unorthodox aiming method on his friends (without firing) many times and perfected his ability to use it. He deduced that over the desert, a fighter pilot can become “invisible” only by extreme maneuvers at close range and that the intensity of the maneuvering was more important than the speed of flying.

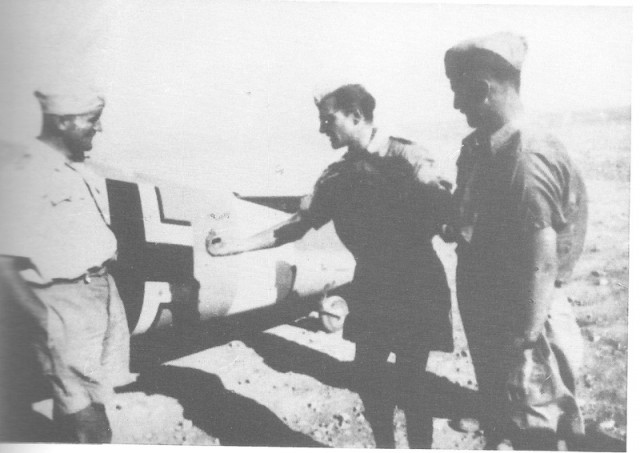

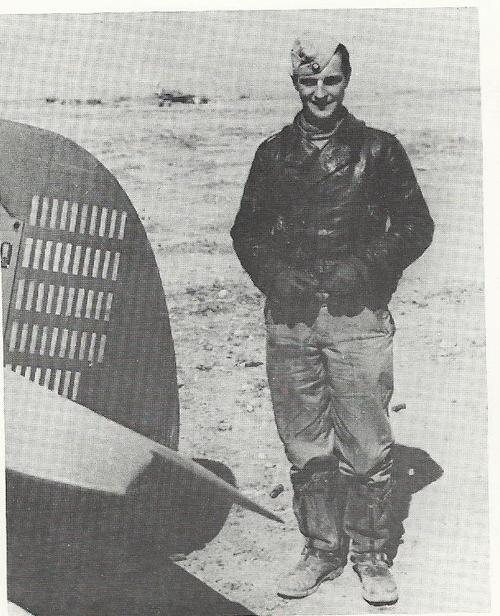

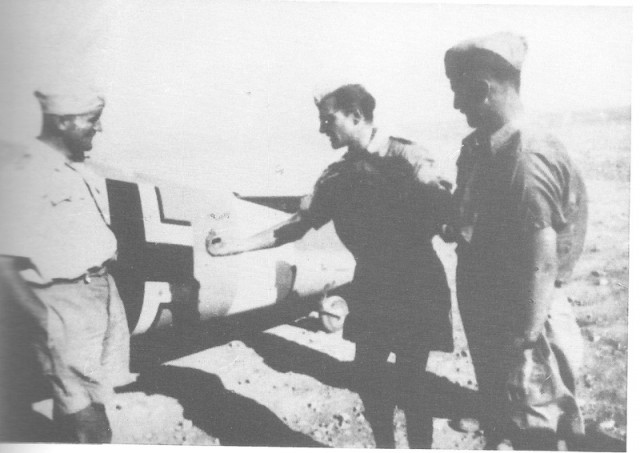

Hans-Joachim Marseille standing next to one of his aerial victories, a Hurricane Mk IIB of No. 213 Squadron RAF, February 1942

Hans-Joachim Marseille standing next to one of his aerial victories, a Hurricane Mk IIB of No. 213 Squadron RAF, February 1942

The Hans Joachim Marseille that emerged from this self-training program was a fighter pilot with superior abilities. He saw enemy aircraft before others did and from greater distances, he could sustain higher G-Force and for longer durations, he made unbelievably sharp turns and achieved better performance with the Me-109 than others.

He greatly outmaneuvered his enemies, nullifying the significant numerical advantage they had, often becoming “invisible” to the enemy pilots by maneuvering so fast, and using his high-deflection short range firing method he achieved an amazing record of lethality, shooting down enemy aircraft with just 15 gun rounds on average.

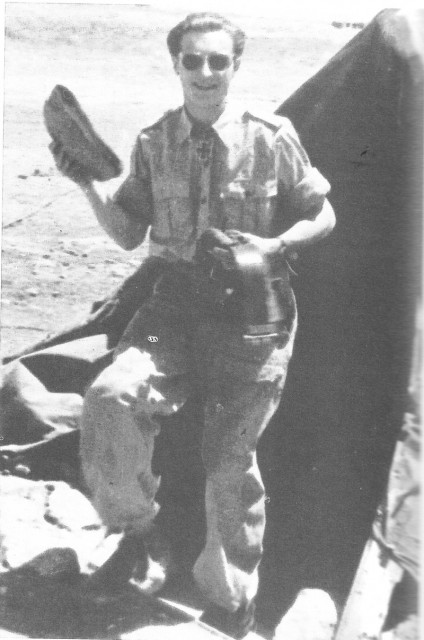

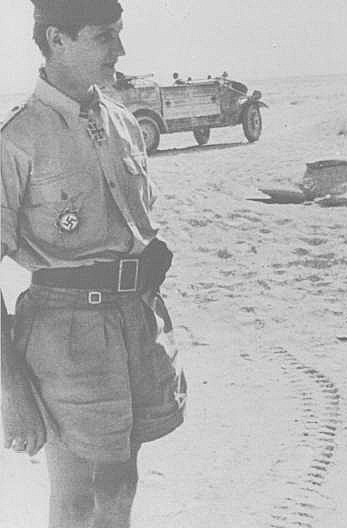

Marseille with Kubelwagen in North Africa

Marseille with Kubelwagen in North Africa

This was the beginning of his amazing series of dogfight victories, which lasted a year until his death in an accident. His most “classic” combat, by some analysts, was on June 6, 1942, at noon. While in a bomber escort mission, he saw a formation of 16 P-40 Tomahawk fighter and ground attack aircraft, but initially remained with his formation, escorting the German bombers. After ten minutes, he left his formation with the escorted bombers and flew alone to attack the 16 Tomahawks, but his faithful wingman followed him.

Marseille climbed above a tight formation of four, then dived at them. From a range of just 200ft, he selected his first victim and turned at him. From a very short range of just 150ft, he fired and shot it down. He then pulled up, turned, and dived at his 2nd victim, shooting it down from a range of 150ft. The others began to dive, but Marseille dived at them, turned at his 3rd victim and shot it down at an altitude of about 3500ft (1km). He passed thru the smoke from his 3rd victim and leveled at low altitude, and then climbed again. He then dived again, at his 4th victim. He fired from just 100ft, but his guns didn’t fire, so he fired his machine guns from very short range and passed thru the debris from his 4th victim.

At the moment he hit his 4th victim, his 3rd victim hit the ground after falling 3500ft, approximately 15 seconds between victories, an indication of Marseille’s speed. The remaining Tomahawks were now all at very low altitude. He leveled at them and quickly closed the distance. He found himself beside one of the Tomahawks, he turned at him and fired, hitting his 5th victim in the engine and the cockpit. He climbed again, watched the remaining Tomahawks, selected a target, dived, leveled, and fired, and passed just above his 6th victim. He then climbed to his wingman that observed the battle from 7500ft above, and then, short of fuel and ammunition, flew back to base.

In 11 minutes of combat, fighting practically alone against a large enemy formation, he shot down six victims, five of them in the first six minutes. He was the only attacker in the battle, and not a single round was fired at him. The surviving Tomahawk pilots said in their debriefing that they were attacked “by a numerically superior German formation which made one formation attack at them, shot down six of their friends, and disengaged.” In a post-war analysis of this dogfight, these pilots testified the same.

On Sept. 26, he shot down his last victims, making a total of 158 confirmed air victories. He received a new Me-109 aircraft but refused to replace his faithful aircraft. His status was such that only an order by Fieldmarshal Kesselring, the supreme commander of the German forces in the southern front, convinced him three days later to use the new aircraft.

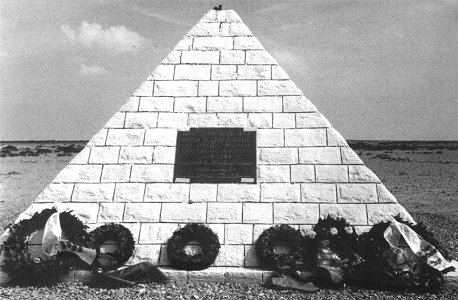

The next morning, Sept. 30, 1942, he flew his 382nd combat mission, a fighter sweep over British territory. They met no enemies and turned back towards the German lines. Marseille then had a technical problem. His new aircraft’s engine cooling system failed, the engine caught fire, and his cockpit was full of smoke. Encouraged by his fellows, Marseille flew his burning new Me-109 three more minutes until he was again over German-held territory. He then turned his aircraft upside down, jettisoned the canopy, and then released himself and fell outside of the burning fighter. Bailing out is not always safe, and Marseille was hit in the chest by the rudder of his Me-109 and lost consciousness, so he did not open his parachute, and fell to the ground and died.

Already highly decorated, he was posthumously awarded the highest German medal, the Knights Cross with Oakleaves, Swords, and Diamonds. Only nine other German aces were awarded this medal. On his grave, his comrades wrote his name and rank and added just one word: undefeated.

Marseille on the tennis court

Marseille on the tennis court

Marseille was the antithesis of the typical German officer. Anti-Nazi, anti-racist, humanistic and openly irreverent towards his superiors with whom he disagreed, he became Germany’s most unlikely national hero. His story is one of stirring emotion, controversy, and enigmatic heroism, and is told by the men and women who knew him.

Above: Marseille (center) with his Jewish friends in school

Above: Marseille (center) with his Jewish friends in school

Above: The Marseille family

Above: The Marseille family

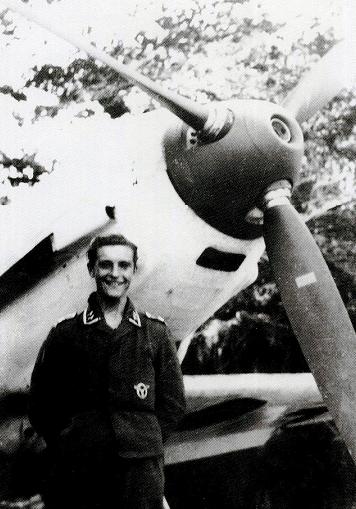

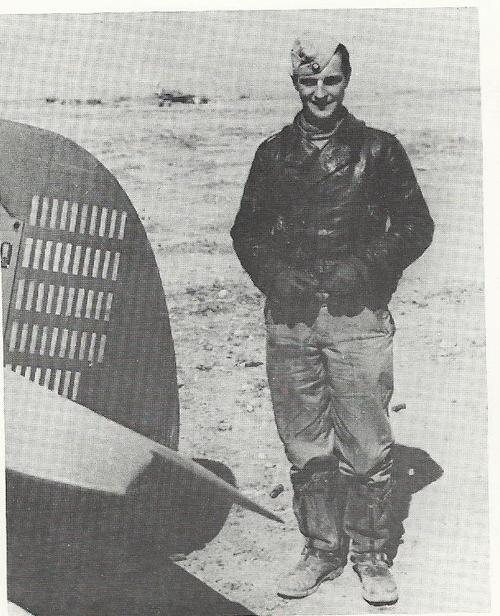

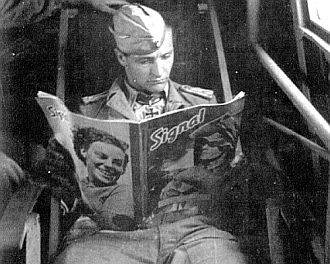

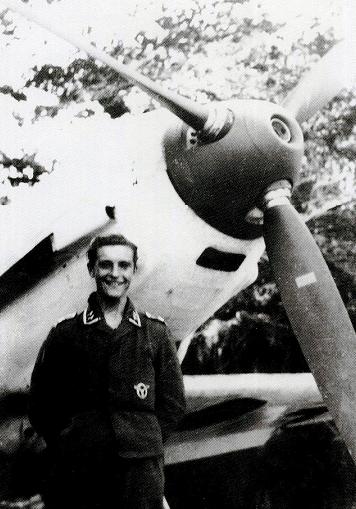

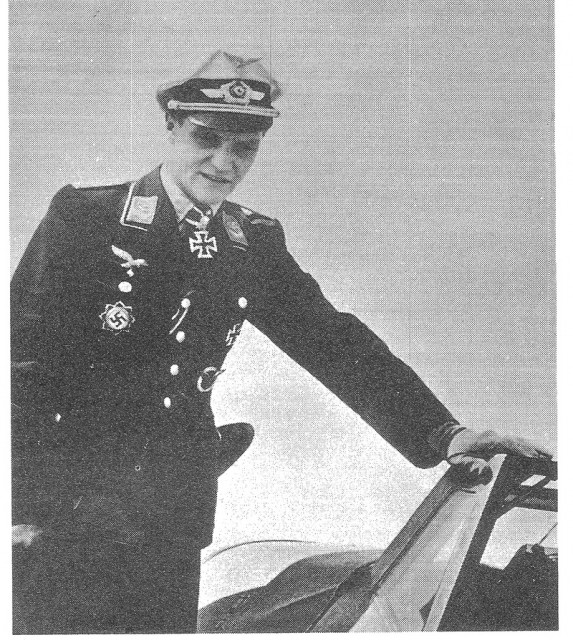

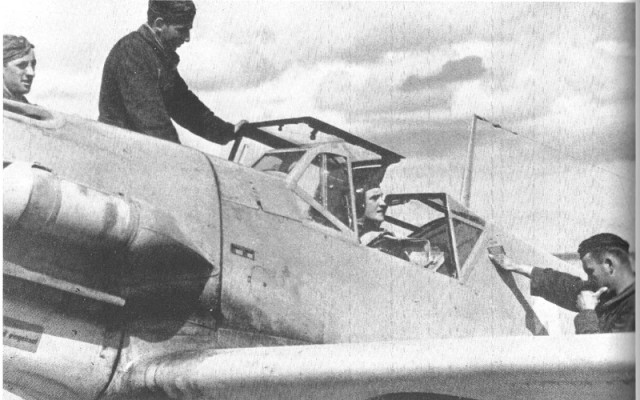

Marseille with his Me-109E4 with LG-2

Marseille with his Me-109E4 with LG-2

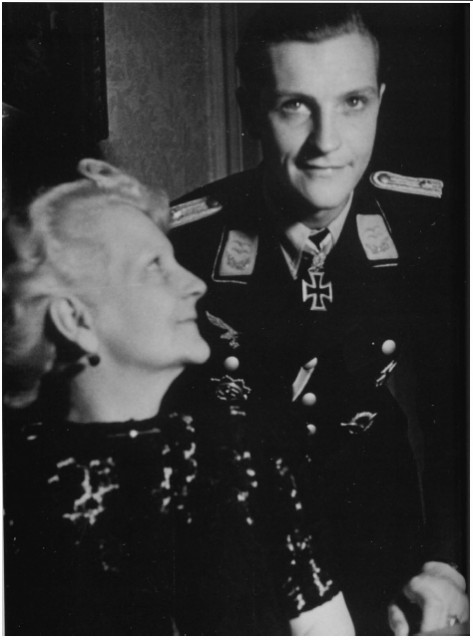

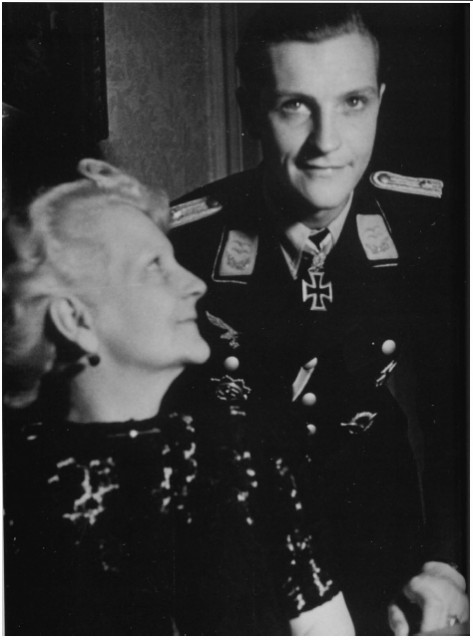

Marseille with his mother

Marseille with his mother

Marseille and mother before his concert

Marseille and mother before his concert

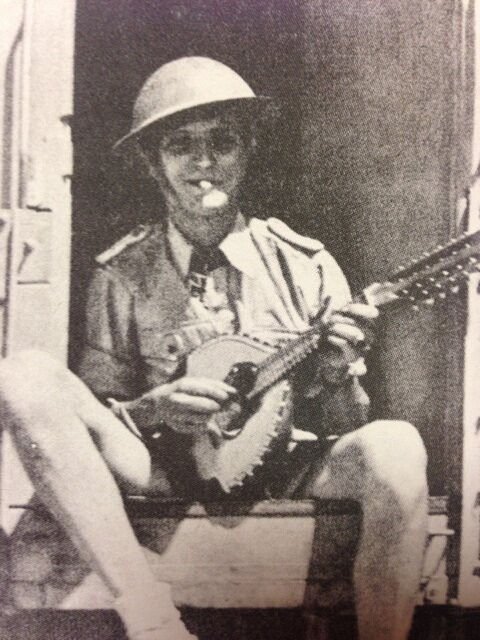

Marseille is displaying his musical skills. Hitler was less than amused

Marseille is displaying his musical skills. Hitler was less than amused

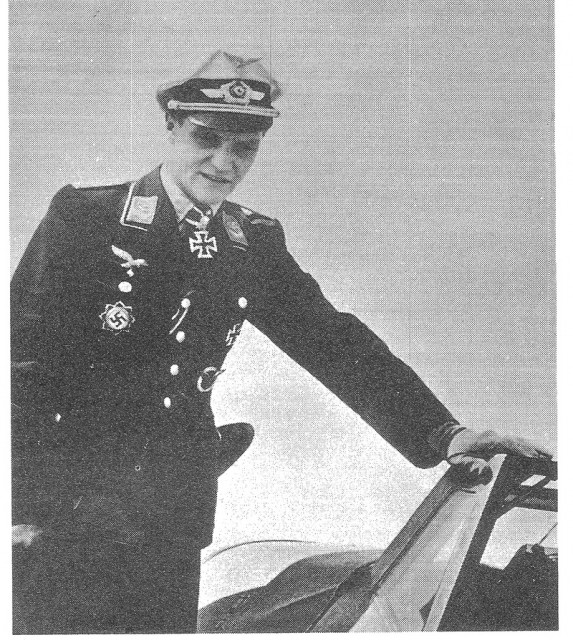

Two portraits of Marseille

Two portraits of Marseille

Marseille

(2nd from right) with fiancee Hanneliese Kupper during his home leave

on his left at the Berlin Palast after the award ceremony

Marseille

(2nd from right) with fiancee Hanneliese Kupper during his home leave

on his left at the Berlin Palast after the award ceremony

Marseille portraits

Marseille portraits

His father: Maj Gen Siegfried Marseille

His father: Maj Gen Siegfried Marseille

Still image from the newsreel of Marseille’s Hitler Youth recruitment tour

Still image from the newsreel of Marseille’s Hitler Youth recruitment tour

Above: Two photos of Marseille with fiancee Hannliese Kupper

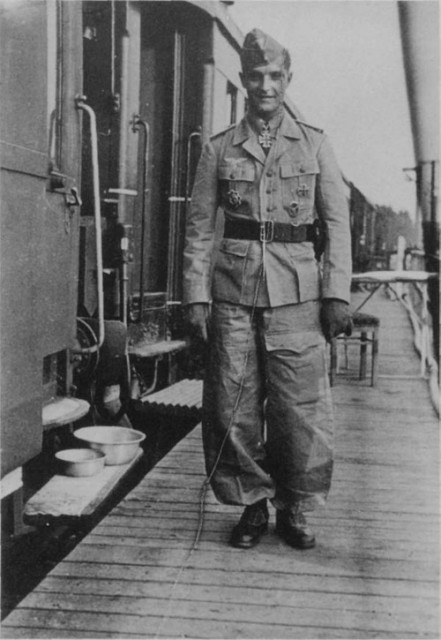

Two photos at the Bahnhoff on his way to meet Adolf Hitler

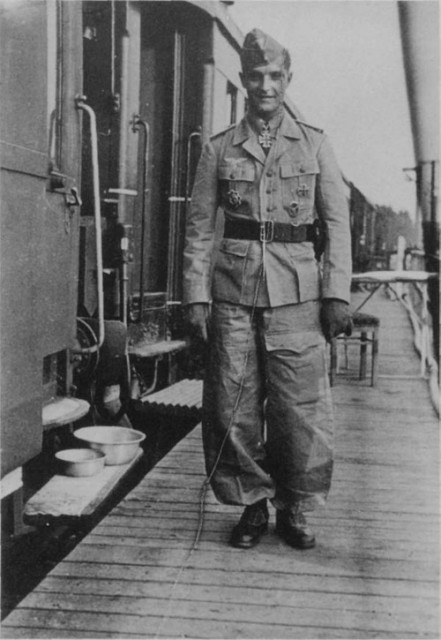

Marseille after receiving the Oak Leaves and Swords

Photo still from the newsreel of their meeting

Photos were taken during the ceremony

Marseille at Augsburg

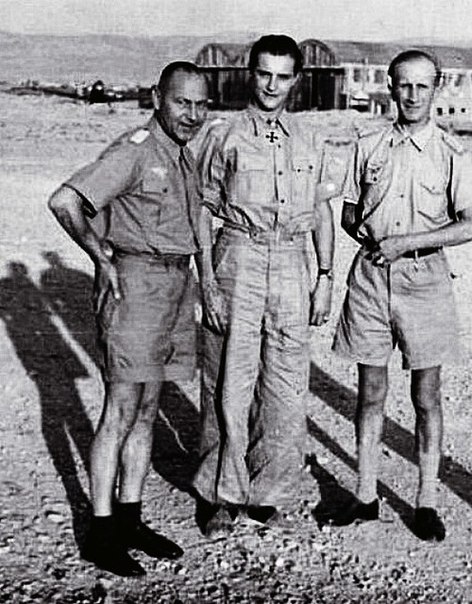

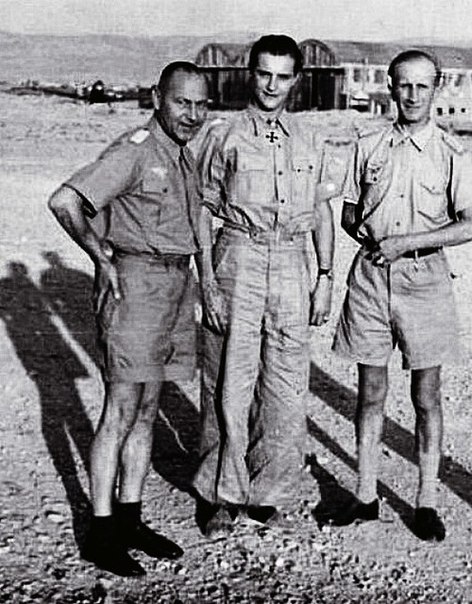

Fritz Wendell, Pohs and Marseille during Me-109G test flights.

Marseille on the cover of the Italian version of The Eagle

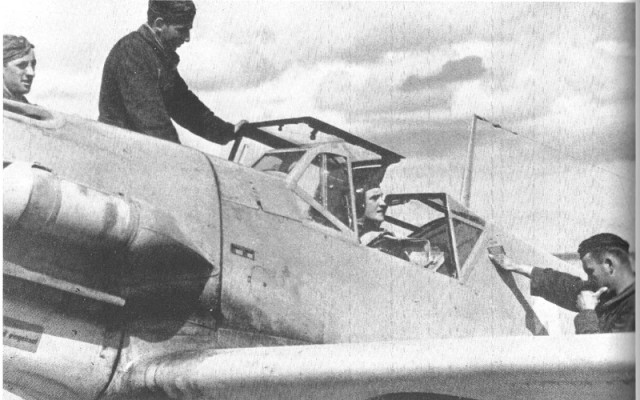

Marseille strapping in

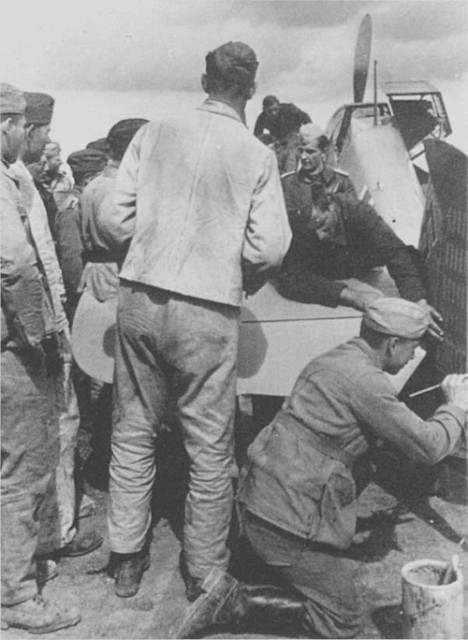

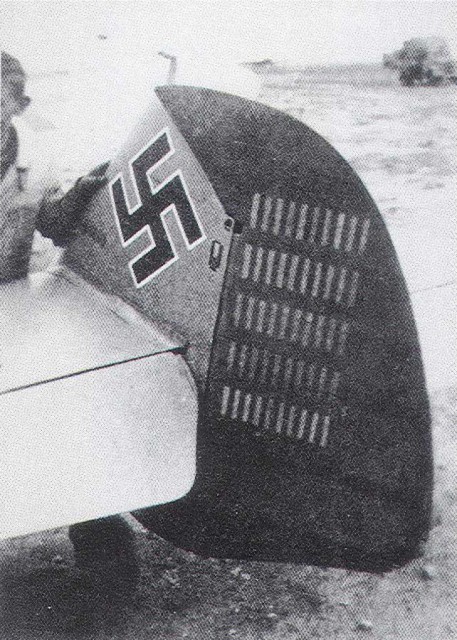

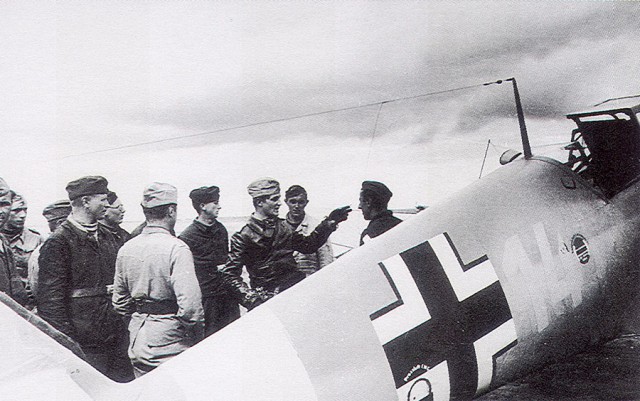

Adding victories to Marseille’s rudder

Marseille with his first Blenheim bomber kill

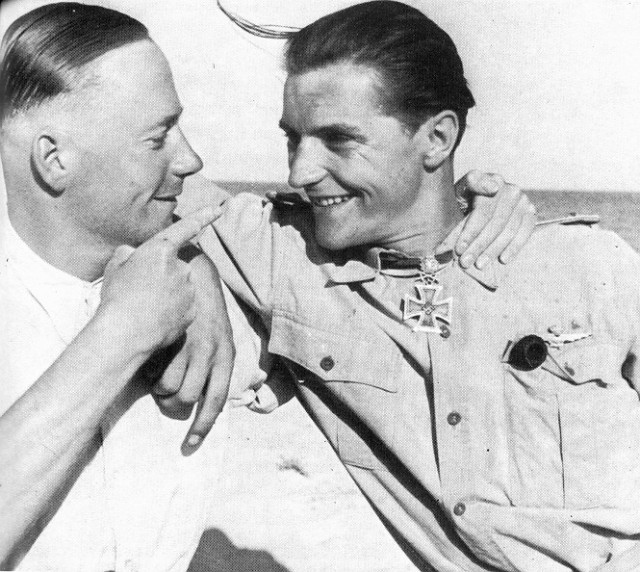

Marseille congratulated returning from a mission and flight to an enemy airfield

Marseille back from a mission. More victories

Possibly Reiner Pottgen (left) with Marseille

Marseille’s rudder with 136 kills

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring awarding the Knight’s Cross

Two photos of Marseille after returning his 5th and final ‘mail’ flight over an enemy airfield

Marseille and the men greeting his latest victory

Marseille discussing a mission

Marseille and Me-109 rudder

The men in Benghazi

Marseille after another mission

Marseille congratulated after his second mission of Sept. 1, 1942

After downing four Hurricanes, Marseille points to an enemy 20mm cannon hole

Marseille dismounting after a mission

Marseille describing his 8 kills in a single sortie

Marseille describing his 8 kills in a single sortie

Marseille describing a battle

Marseille on a successful return

Marseille preparing for a mission take off

Life and War in the Desert

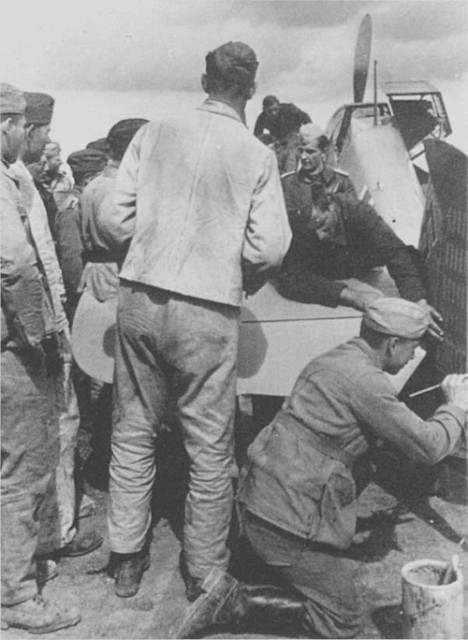

Christening Hans-Arnold “Fifi” Stahlschmidt’s new Me-109F4. This was the aircraft in which he became missing in action. He has never been found.

Marseille walks away after another successful mission

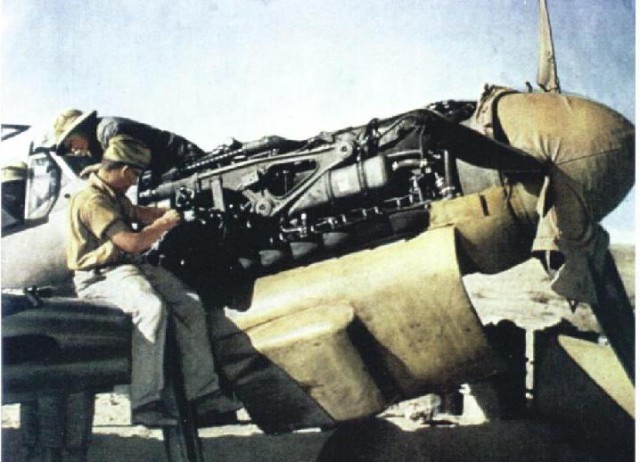

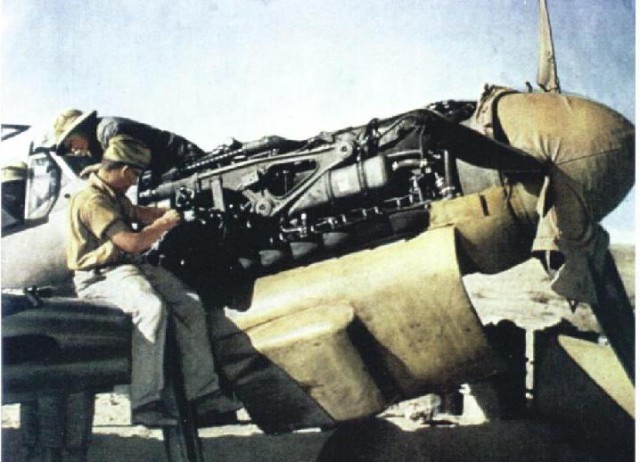

Mechanics cleans the 20mm cannon barrel

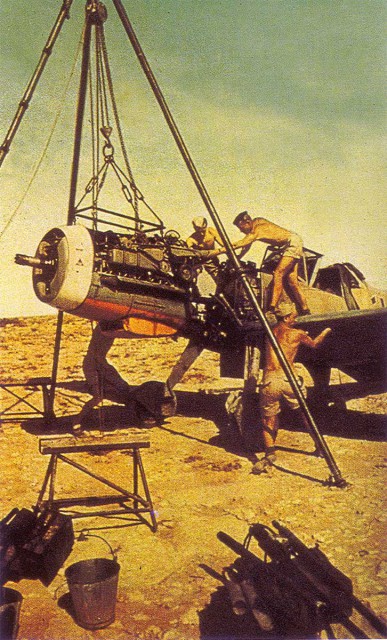

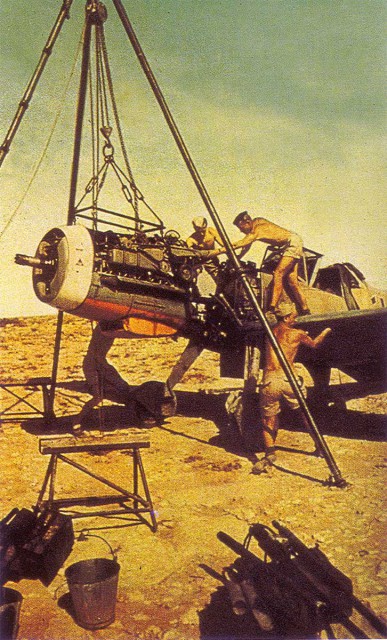

Above and Below: Engine repair on a Me-109F and Me-109E respectively

Marseille driving his Kubelwagen with Werner Schroer in the back

Marseille exhausted

Marseille exhausted

Marseille after receiving the Knight’s Cross

Marseille and Mathias

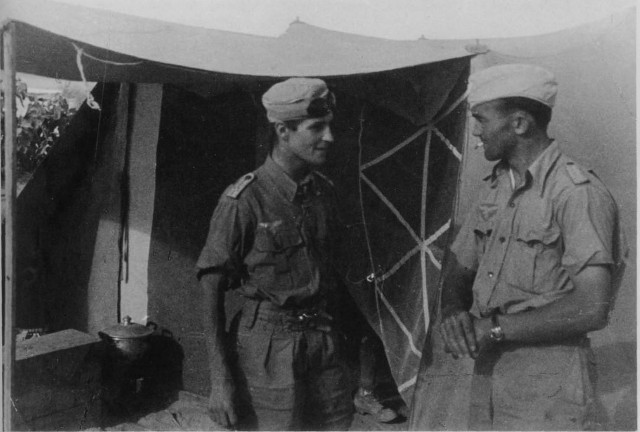

Marseille with Eduard Neumann

Marseille after the telephone call from Field Marshall Erwin Rommel informing him that he would meet Hitler again to receive the Diamonds.

Marseille after another mission

Marseille on the way to meet Mussolini

s

sHans Joachim Marseille, a young German fighter pilot, was the most amazing, unique, and lethal ace of World War 2. A non-conformist and brilliant innovator, he developed his own personal training program and combat tactics and achieved amazing results, including 17 victories in one day, and an average lethality ratio of just 15 gun rounds per victory. Marseille was described by Adolf Galland, the most senior German ace, with these words: “He was the unrivaled virtuoso among the fighter pilots of World War 2. His achievements were previously considered impossible.”

A charming person, he had such busy nightlife that sometimes he was too tired to be allowed to fly the next morning. He also loved American Jazz music, which was very politically incorrect in the Nazi military. As a result, he was transferred to another unit as a punishment for “Insubordination”. His new unit, fighter wing 27, was relocated in April 1941 to the hot desert of North Africa, where he quickly achieved two more victories but was also shot down again and still had disciplinary problems.

Marseille claimed his 7th aerial victory on 28 September 1940 but had to crash land near Théville due to engine failure.

Marseille’s self-training program

Vision – Marseille decided to adapt his eyes to the powerful desert sun and the desert atmosphere and to adapt his body to the desert’s conditions. He stopped wearing sun glasses, deliberately exposed his eyes to the desert sun, and shifted from alcohol to milk. He also noticed that in the intensely lit desert atmosphere, aircraft can be detected from greater distances than over Europe and deduced that hiding and surprise are less practical over the desert than in the cloudy sky over Europe.G-Force – Marseille worked endlessly to strengthen his abdominal and leg muscles to enhance his ability to sustain higher G-Force and for longer durations during dogfights better than the average fighter pilot. G-Force is the enormous centrifugal force experienced when a fighter aircraft makes sharp turns during a dogfight. The modern G-suit that helps pilots sustain it was not yet invented in World War 2.

Aerobatics – Marseille used every opportunity to perform breathtaking aerobatics. In addition to free entertainment to his friends on the ground, this also gave him an outstanding control and confidence in extremely maneuvering his Messerschmitt 109 aircraft.

Intelligence – he began to read every possible intelligence information he could find to maximize his knowledge and understanding of the enemy.

Tactics – That’s where Marseille marked himself as a great innovator of air warfare, and he kept improving. He claimed that in the perfect visual conditions over the desert, large formations are in a visual disadvantage against highly maneuvering single aircraft. He preferred to fight alone, with a single wingman providing warnings from a safe distance. He claimed that when fighting alone in a short-range dogfight, he could quickly fire at anything he saw while the attacked formation’s pilots were confused, hesitated, and switched to a defensive position that further increased the lone attacker’s chances.

He also claimed that fighting alone eliminates the high risk of firing at or colliding with a wingman in such extreme maneuvering. Marseille said that in such conditions, there’s a lower chance and too little time for the usual chase attack method, and preferred to use high angle deflection firing from short range while making a sharp turn. In doing so, he never used his gun sight and instead fired a very short burst at the passing target in the split second when its leading edge, its propeller, disappeared from his eyes behind his aircraft’s nose.

He calculated that when firing a short burst at this position, his gun rounds will hit the target’s engine and cockpit, and he trained in this unorthodox aiming method on his friends (without firing) many times and perfected his ability to use it. He deduced that over the desert, a fighter pilot can become “invisible” only by extreme maneuvers at close range and that the intensity of the maneuvering was more important than the speed of flying.

Hans-Joachim Marseille standing next to one of his aerial victories, a Hurricane Mk IIB of No. 213 Squadron RAF, February 1942

Hans-Joachim Marseille standing next to one of his aerial victories, a Hurricane Mk IIB of No. 213 Squadron RAF, February 1942The Hans Joachim Marseille that emerged from this self-training program was a fighter pilot with superior abilities. He saw enemy aircraft before others did and from greater distances, he could sustain higher G-Force and for longer durations, he made unbelievably sharp turns and achieved better performance with the Me-109 than others.

He greatly outmaneuvered his enemies, nullifying the significant numerical advantage they had, often becoming “invisible” to the enemy pilots by maneuvering so fast, and using his high-deflection short range firing method he achieved an amazing record of lethality, shooting down enemy aircraft with just 15 gun rounds on average.

Marseille with Kubelwagen in North Africa

Marseille with Kubelwagen in North AfricaThe Star Of Africa

He first demonstrated his new abilities on Sept. 24, 1941. During a fighter sweep, he suddenly broke formation and hurried to a direction where no one saw anything. When the formation caught up with him, he already shot down a bomber. Later the same day, his formation of six Me-109s met a formation of 16 Hurricanes. Marseille and his wingman were ordered to provide cover to the other four Me-109s, which attacked the Hurricanes, but after three Hurricanes had been shot down, Marseille told his wingman to cover him and attacked a formation of four Hurricanes. He dived at them, leveled at their altitude, and shot down two Hurricanes in a single burst while in a sharp turn. He then dived below the Hurricanes to gather some speed again, and then climbed back to them and shot down the third Hurricane. At that stage, the two formations disengaged each other, but Marseille climbed alone to a higher altitude and later dived at the retreating Hurricanes and shot down the 4th Hurricane, his 5th victory that day, and only then flew alone back to base. “I believe now I got it,” he said to a friend.This was the beginning of his amazing series of dogfight victories, which lasted a year until his death in an accident. His most “classic” combat, by some analysts, was on June 6, 1942, at noon. While in a bomber escort mission, he saw a formation of 16 P-40 Tomahawk fighter and ground attack aircraft, but initially remained with his formation, escorting the German bombers. After ten minutes, he left his formation with the escorted bombers and flew alone to attack the 16 Tomahawks, but his faithful wingman followed him.

Marseille climbed above a tight formation of four, then dived at them. From a range of just 200ft, he selected his first victim and turned at him. From a very short range of just 150ft, he fired and shot it down. He then pulled up, turned, and dived at his 2nd victim, shooting it down from a range of 150ft. The others began to dive, but Marseille dived at them, turned at his 3rd victim and shot it down at an altitude of about 3500ft (1km). He passed thru the smoke from his 3rd victim and leveled at low altitude, and then climbed again. He then dived again, at his 4th victim. He fired from just 100ft, but his guns didn’t fire, so he fired his machine guns from very short range and passed thru the debris from his 4th victim.

At the moment he hit his 4th victim, his 3rd victim hit the ground after falling 3500ft, approximately 15 seconds between victories, an indication of Marseille’s speed. The remaining Tomahawks were now all at very low altitude. He leveled at them and quickly closed the distance. He found himself beside one of the Tomahawks, he turned at him and fired, hitting his 5th victim in the engine and the cockpit. He climbed again, watched the remaining Tomahawks, selected a target, dived, leveled, and fired, and passed just above his 6th victim. He then climbed to his wingman that observed the battle from 7500ft above, and then, short of fuel and ammunition, flew back to base.

In 11 minutes of combat, fighting practically alone against a large enemy formation, he shot down six victims, five of them in the first six minutes. He was the only attacker in the battle, and not a single round was fired at him. The surviving Tomahawk pilots said in their debriefing that they were attacked “by a numerically superior German formation which made one formation attack at them, shot down six of their friends, and disengaged.” In a post-war analysis of this dogfight, these pilots testified the same.

The fatal accident

The 22 years old Hans Joachim Marseille became a star, and he kept improving with experience. On Sept. 1, 1942, a month before his death, he shot down 17 enemies in one day, including eight victories in 10 minutes, in his 2nd sortie that day. During this month, he shot down 54 enemy aircraft. Already the youngest Captain in the German Air Force, he was promoted to Major. He taught his methods to his friends, but none of them was able to match his level of achievements in using these methods.On Sept. 26, he shot down his last victims, making a total of 158 confirmed air victories. He received a new Me-109 aircraft but refused to replace his faithful aircraft. His status was such that only an order by Fieldmarshal Kesselring, the supreme commander of the German forces in the southern front, convinced him three days later to use the new aircraft.

The next morning, Sept. 30, 1942, he flew his 382nd combat mission, a fighter sweep over British territory. They met no enemies and turned back towards the German lines. Marseille then had a technical problem. His new aircraft’s engine cooling system failed, the engine caught fire, and his cockpit was full of smoke. Encouraged by his fellows, Marseille flew his burning new Me-109 three more minutes until he was again over German-held territory. He then turned his aircraft upside down, jettisoned the canopy, and then released himself and fell outside of the burning fighter. Bailing out is not always safe, and Marseille was hit in the chest by the rudder of his Me-109 and lost consciousness, so he did not open his parachute, and fell to the ground and died.

Already highly decorated, he was posthumously awarded the highest German medal, the Knights Cross with Oakleaves, Swords, and Diamonds. Only nine other German aces were awarded this medal. On his grave, his comrades wrote his name and rank and added just one word: undefeated.

Two photos of Marseille graduating high school

Marseille on the tennis court

Marseille on the tennis courtMarseille was the antithesis of the typical German officer. Anti-Nazi, anti-racist, humanistic and openly irreverent towards his superiors with whom he disagreed, he became Germany’s most unlikely national hero. His story is one of stirring emotion, controversy, and enigmatic heroism, and is told by the men and women who knew him.

Above: Marseille (center) with his Jewish friends in school

Above: Marseille (center) with his Jewish friends in school Above: The Marseille family

Above: The Marseille family Marseille with his Me-109E4 with LG-2

Marseille with his Me-109E4 with LG-2 Marseille with his mother

Marseille with his mother Marseille and mother before his concert

Marseille and mother before his concert Marseille is displaying his musical skills. Hitler was less than amused

Marseille is displaying his musical skills. Hitler was less than amused

Two portraits of Marseille

Two portraits of Marseille Marseille

(2nd from right) with fiancee Hanneliese Kupper during his home leave

on his left at the Berlin Palast after the award ceremony

Marseille

(2nd from right) with fiancee Hanneliese Kupper during his home leave

on his left at the Berlin Palast after the award ceremony Marseille portraits

Marseille portraits His father: Maj Gen Siegfried Marseille

His father: Maj Gen Siegfried Marseille Still image from the newsreel of Marseille’s Hitler Youth recruitment tour

Still image from the newsreel of Marseille’s Hitler Youth recruitment tour

Above: Two photos of Marseille with fiancee Hannliese Kupper

Marseille Meets Hitler

Two photos at the Bahnhoff on his way to meet Adolf Hitler

Marseille after receiving the Oak Leaves and Swords

Photo still from the newsreel of their meeting

Photos were taken during the ceremony

Fritz Wendell, Pohs and Marseille during Me-109G test flights.

Marseille on Missions

Marseille on the cover of the Italian version of The Eagle

Marseille strapping in

Adding victories to Marseille’s rudder

Marseille with his first Blenheim bomber kill

Marseille congratulated returning from a mission and flight to an enemy airfield

Marseille back from a mission. More victories

Possibly Reiner Pottgen (left) with Marseille

Marseille’s rudder with 136 kills

Field Marshal Albert Kesselring awarding the Knight’s Cross

Two photos of Marseille after returning his 5th and final ‘mail’ flight over an enemy airfield

Marseille and the men greeting his latest victory

Marseille discussing a mission

Marseille and Me-109 rudder

The men in Benghazi

Marseille after another mission

Marseille congratulated after his second mission of Sept. 1, 1942

After downing four Hurricanes, Marseille points to an enemy 20mm cannon hole

Marseille dismounting after a mission

Marseille describing his 8 kills in a single sortie

Marseille describing his 8 kills in a single sortie

Marseille describing a battle

Marseille on a successful return

Marseille preparing for a mission take off

Christening Hans-Arnold “Fifi” Stahlschmidt’s new Me-109F4. This was the aircraft in which he became missing in action. He has never been found.

Marseille walks away after another successful mission

Mechanics cleans the 20mm cannon barrel

Above and Below: Engine repair on a Me-109F and Me-109E respectively

Marseille driving his Kubelwagen with Werner Schroer in the back

Marseille exhausted

Marseille exhausted

Marseille and Mathias

Marseille with Eduard Neumann

Marseille after the telephone call from Field Marshall Erwin Rommel informing him that he would meet Hitler again to receive the Diamonds.

Marseille after another mission

Marseille on the way to meet Mussolini

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου