The dream of a supersonic STOVL (Short Take-Off and Vertical Landing) fighter has been striven toward for over half of the history of heavier-than-air flight. When the F-35B reaches real operational readiness with the USMC, it will be a very significant event. Lockheed Martin will have succeeded where dozens of the world’s greatest aircraft design houses have failed. The tortuous road which led, via the Harrier, to the F-35B started with NATO requirement NBMR-3 of 1961. This almost led to a British superfighter, the Hawker P.1154.

Help Hush-Kit to remain independent by donating here. Donations enable us to carry on creating unusual and engaging articles. Thank you.

The author of Catch-22, Joseph Heller, fought with the 340th Bomb Group in Italy as a bombardier on B-25s. His commander was one Colonel Willis Chapman. Following the war Chapman set up USAF’s first jet bomber force. In 1956, Chapman was sent to Paris as part of the Pentagon’s Mutual Weapons Development Plan (MWDP) field office. His mission was to source and help develop new military technologies from European sources and strengthen Europe’s contribution to NATO.

Chapman

was commander of the ‘Catch-22’ bomber group. Chapman’s daughter’s

excellent book revealed that the characters in the book were barely

different to those in reality.

The basic principle of Wibault’s concept was that the thrust of an engine could be directed through four swiveling nozzles. The thrust could then be directed downwards to allow an aircraft to take-off vertically or swiveled back to facilitate forward flight. Wibault had designed a Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) fighter incorporating this principle.

Doomsday fighters

Why VTOL? By the mid-1950s it was obvious to many western military planners that, in the event of war, Warsaw Pact forces would quickly obliterate NATO airbases. For NATO aircraft to mount counter- attacks (some with tactical nuclear weapons), they would need to be able to operate from rough unprepared airstrips. These capability could turn air arms into survivable, ‘guerrilla’ forces able to fight on after the apocalypse. VTOL was also tempting to many navies; it could eliminate the traditional hazards of carrier landing. If an aircraft could ‘stop’ before it landed, the task of landing on a tiny, pitching deck would be far easier. Likewise, it could liberate ships from the need to carry enormously heavy catapult launch systems; it could even allow small ships to carry their own, high performance, escort aircraft.

Thank you for reading Hush-Kit. Our site is absolutely free and we have no advertisements. If you’ve enjoyed an article you can donate here– it doesn’t have to be a large amount, every pound is gratefully received. If you can’t afford to donate anything then don’t worry.

At the moment our contributors do not receive any payment but we’re hoping to reward them for their fascinating stories in the future.

Hooker’s expertise

Chapman was very impressed and brought the idea to the attention of Dr. Stanley Hooker, director of the British Bristol Aero Engine Company. At this time Bristol were at the forefront of jet technology.

Hooker was also impressed. The VTOL research aircraft then flying used a series of batty principles which either involved rotating the whole fuselage (the tail-sitters), the engine of the aircraft (sometimes with the whole wing) or carried a battery of auxiliary lift-jets which once in flight were dead weight. All were complex and involved very large design compromises. Contrary to this, Wibault’s principle was simplicity itself; it involved a single fixed-engine, and would allow for the precise control of the vectored thrust.

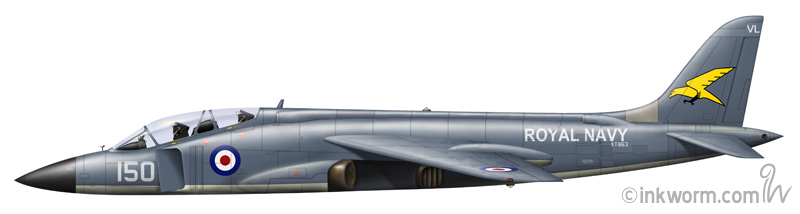

How the P.1154 would have looked in RAF service. This aircraft is seen in the colours of No.29 Squadron.

At the 1957 Farnborough air show Hooker and Camm met Chapman. They showed him the design for P.1127. By early 1958 the MWDP were funding the BE.53 engine. The P.1127 fighter was struggling to get funding, as Britain’s Ministry of Defence believed that there would be no future manned bombers or fighters. This belief was expressed in the 1957 White Paper on Defence (Cmnd. 124) by Duncan Sandys- the most hated document in British aviation history.

Duncan Sandys had been Chairman of a War Cabinet Committee for defence against German flying bombs and rockets during World War II, and during this tenure he had accidentally revealed information about where the V1s and V2s were landing. This was a shocking error, allowing the Germans to accurately calibrate their weapons trajectories and endangering British lives. It also threatened to uncover Agent Zig-Zag, the famed double-agent, who at the time was feeding German intelligence false reports of bomb damage in London. His wartime experiences may have informed his belief in the late 1950s that missiles could take over from manned aircraft.

Help Hush-Kit to remain independent by donating here. Donations enable us to carry on creating unusual and engaging articles. Thank you.

Success

His 1957 report was also ill-judged, as 55 years later the UK is about to receive a new manned fighter (the F-35B) that is expected to remain in service for the next forty years.

As there was little official support in the UK, Hawker decided to fund building two prototypes itself, with some research support from NASA (who noted that, unlike rival VTOL aircraft, the P.1127 would not need a complex auto-stabilisation system). By the time Hawker had started building the prototypes, the MoD was interested and funded the building of four more. The P.1127 first flew on 19 November 1960 and proved very successful. It could take-off and land vertically with ease, something dozens of research aircraft around the world had failed to do. But, it shared a deficiency with its rivals; an aircraft with a high enough thrust-to-weight ratio to lift vertically could carry little in the way of fuel or payload. This is where the P.1127 really came into its own. It was discovered that by putting the exhaust nozzle into an interim position (45 degrees) the aircraft could take-off in very short distances at very low speeds (60 knots, around half the taking-off or ‘rotation’ speed of a Hawker Hunter). At this point VTOL gave way to V/STOL (Vertical/Short Take-Off and Landing).

The MoD was now warming to the idea of a P.1127-based type and the RAF prepared a draft requirement (OR345) for a new V/STOL fighter of modest capabilities.

In 1961 NATO Basic Military Requirement 3 (NBMR-3) was issued. This followed on from the 1953 NBMR-1 (for a light weight tactical strike fighter, which was won by the Fiat G.91 and the Breguet Taon – though the Taon never entered service). The NBMR-2 was for a maritime patrol aircraft, and was won by the Breguet Br.1150 Atlantic.

NBMR-3 specification called for a single-seat tactical close-support and reconnaissance V/STOL fighter. The requirement demanded a combat radius of 250 nautical miles at a minimum sea level speed of Mach 0.92, and 500 ft altitude, while carrying a 2,000 lb store. This was a doomsday fighter-bomber, able to launch a retaliatory tactical nuclear strike from whatever improvised airstrips were available – even including selected motorway sections, heavily cratered main runways or worse.

Hush-kit is reminding the world of the beauty of flight.

follow my vapour trail on Twitter: @Hush_kit

Help Hush-Kit to remain independent by donating here. Donations enable us to carry on creating unusual and engaging articles. Thank you.

The prospect of providing NATO with a common fighter soon attracted most major Western aircraft companies. NBMR-3 became the biggest international design competition ever held. Two months later NBMR-3 was split into two; AC 169a would cover a F-104G replacement, and kept the original demands: AC 169b was to be a Fiat G.91 replacement. AC 169b differed to AC 169a in calling for a lower payload-range requirement of 180 nautical mile range with 1,000 lb store.

Enter P.1154

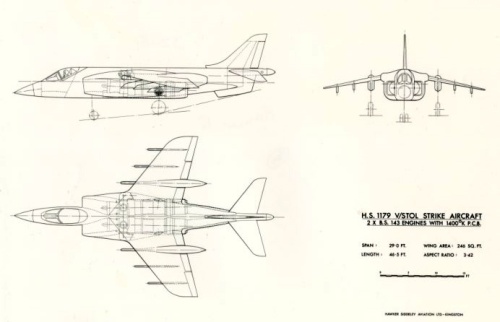

At this point OR345 was dropped in favour of NBMR-3. Hawker Siddeley’s bid was the monstrous P.1154 powered by the insanely powerful Bristol Siddeley BS.100 engine.

The BS.100 was designed to produce a mighty 33,000 lb of thrust in reheat, around twice the power of the most powerful fighter engine then in service. The only engine with more power at the time was the Pratt & Whitney J58, which had yet to fly. The J58 was being developed for the top-secret Lockheed A-12 spy plane, which evolved into the SR-71 Blackbird. However, unlike the BS.100, at the speeds the J58 produced its maximum thrust, it was effectively a ramjet. As another example of how powerful the BS.100 was, the first fighter engine with greater power did not enter service until 2005 (44 years later). The engine was the Pratt & Whitney F119 and the aircraft was the Lockheed Martin F-22 Raptor. The potent BS.100 would have given the P.1154 a Mach 1.7 top speed, an unprecedented thrust-to-weight ratio and a scorching rate-of-climb. The aircraft was to be far more than just a brutish hot-rod, it was to be equipped with some very advanced avionics. Ferranti would provide the P.1154 with a radar which was at least a generation ahead of any other. The radar would feature both air-to-air and terrain-following modes. This was a true multi-mode radar, planned at a time when the world’s best fighters were carrying crude air interception radars with tiny ranges. The P.1154 would have one of the world’s first Head-Up Displays (HUD). The HUD is a piece of glass in front of the pilot with vital flight information projected onto it, which allows the pilot to keep his eyes up and looking ‘out’ and not to be distracted by looking down at instruments in the cockpit. The aircraft would also be fitted with another piece of innovative equipment, Inertial Navigation System (INS), a technology first seen in the V2 rockets that Sandys’ had accidentally aided!

But Hawker Siddeley was not the only company to be lured in by the big bucks promised by NBMR-3. Italy had been fucked over by NBMR-1. The contest had declared Fiat’s G.91 the winner, but nationalism got in the way. National governments which had been more than happy to support their own bids to the contest, grew shy when Italy won the contest, and the G.91 did not receive orders on the scale that could have been expected.

This time Fiat entered the handsome G.95: https://hushkit.wordpress.com/2012/07/27/sixties-superfighters-the-original-jsf-the-italian-vstol-g-95-resistenza/. France, Germany, and even the Netherlands, submitted designs. The Netherlands’ Fokker D.24 Alliance, to be produced with help from US’ company Republic was also powered by the BS.100. The very ambitious D.24 was also variable sweep (swing-wing).

A notional RAF No.111

Squadron P.1154. The Paveway IVs are not a representative weapon-load,

as the type would have probably been retired prior to this weapon’s

service entry.

Hawker and Bristol’s P.1154 was declared the winner, but history repeated itself. Though nobody was tied to buying the winners of NBMR contests, it still seems unfair that no country outside of Britain was forthcoming in wanting to invest in P.1154. Hawker had been stitched-up far worse than Fiat had been. Still, at least Hawker still had a generous MoD budget to work with, and the type was elected to replace RAF Hunters and RN Sea Vixens- what else could go wrong? Two things. The first was the differing needs of the Royal Navy and the RAF. The RAF wanted a single-engined, single seater. The Navy wanted a two-seat, twin-engined aircraft. To some degree both the Navy’s wants may have been driven by safety regulations regarding nuclear-armed aircraft (though the single-seat Scimitar carried the Red Beard tactical nuclear bomb). The Royal Navy was also impressed by the McDonnell (later MD) F-4 Phantom II, and there were some within the Admiralty which considering this a safer option. Giving the P.1154 twin engines would involve a complex modification of the design. The BS.100 was too big, so Rolls-Royce Speys were selected. To stop a twin-engined P.1154 flipping over in the event of a single engine failure, a complicated twin-ducting concept was added (comparable to the V-22 Osprey’s transmission system). The Royal Navy also wanted a larger radar.

On top of this, P.1154 threatened the existence of the Navy’s big carriers, if these new machines could take-off in next to no distance, why did the navy need massive expensive carriers? It should be noted that the Navy intended to catapult-launch their P.1154s, using an US style of operation. The Navy’s self-preservation instinct was kicking in. While the RAF P.1154s could have been made to work (with limitations), many, even at Hawker, doubted the viability of the naval variant.

Technical problems

If the first major problem facing the P.1154 was inter-service differences, the second set were technical. The P.1154 would be firing hot, after-burning exhaust from its front nozzles down onto runways or carrier decks. The temperature was great enough to melt asphalt or distort steel- this was a big problem (the Yak-141 would later encounter similar problems). It would also churn up a potentially dangerous cloud of any present dirt.

Added to this was hot gas re-ingestion (HGR). The aircraft would be ‘breathing in’ its own hot exhausts on landing. This re-circulating hot air would raise the temperature in the engine to more than it liked, a very serious problem.

On 2 February 1965, the incoming Labour government, led by Harold Wilson, cancelled the P.1154 on cost grounds. Was this to be the end of V/STOL fighters? Well, fortunately not. While the P.1154 was being designed, Hawker had been busy developing the P.1127 into the Kestrel, with the help of funds from Britain, West Germany and the USA (initially from the US Army). This of course led to the Harrier, the famous jump-jet which today remains in service with the United States, Spain, Italy and India.

Hush-Kit would like to thank: Chris Sandham-Bailey from inkworm.com for his wonderful profiles, and Nick Stroud for providing access to his photographic archive.

If you enjoyed this, check out our article on the BAC TSR.2: https://hushkit.wordpress.com/2012/05/14/the-bac-tsr-2-bombing-the-myth/ and the FIAT G.95: https://hushkit.wordpress.com/2012/07/27/sixties-superfighters-the-original-jsf-the-italian-vstol-g-95-resistenza/

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου