Miniature

Bastille carved from rubble of the original Bastille, on view in the

Musée Carnavalet in Paris. (photo by the author for Hyperallergic)

The Musée Carnavalet in Paris houses one of these relics: a miniature Bastille made from stone from the prison. It’s one of 83 models that Palloy sent out to France’s newly formed departments, which divided the country into new bureaucratic regions. The earliest models were carved right from the rock, while later mini Bastilles were made by casting pulverized stone. Along with paintings, etchings, and other visual representations, these building miniatures provide a material link to the moment when the mighty stone towers that had represented oppression by the monarchy became the ultimate symbol of the French Revolution. (Even though the Bastille was only holding seven prisoners at the time.)

The tiny Bastilles, with their towers and carved windows, were just one component of Palloy’s salvaging activities. He also melted prisoner chains into medals, etched plaques into stone, and even gifted a prison key to George Washington through the Marquis de Lafayette, which is now on view at Mount Vernon.

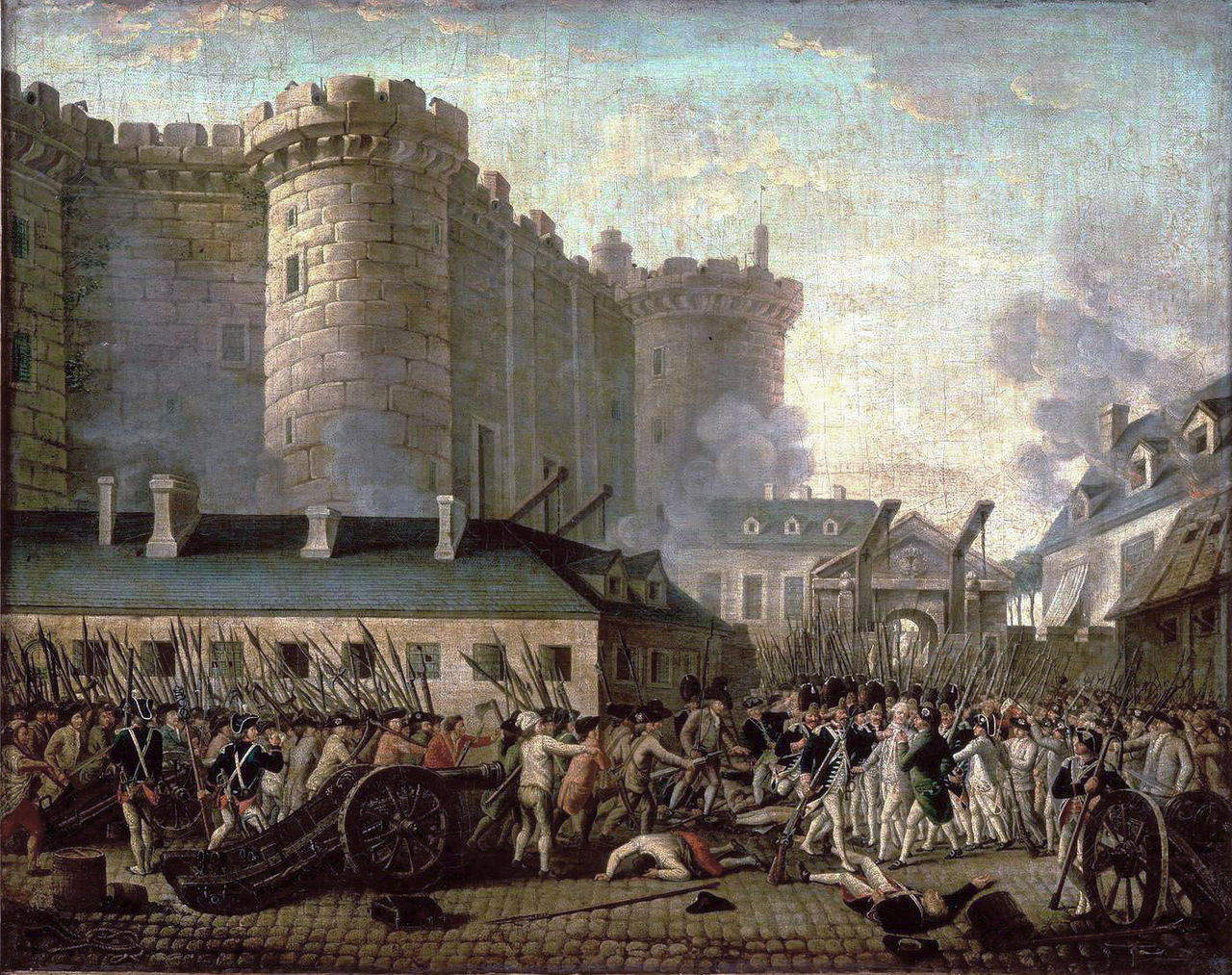

Henry Singleton, “The Storming of the Bastille” (nd), oil on canvas (via Wikimedia)

In a 1792 speech, Palloy reportedly said: “France is a new world and in order to hold on to this achievement, it is necessary to sow the rubble of our old servitude everywhere.” These Bastille maquettes helped cement the fallen icon of past control as a symbol of new liberty.

Anonymous, “Storming of the Bastille and the arrest of the Governor M. de Launay” (nd), oil on canvas (via Museum of the History of France)

Carved miniature of the Bastille at the Musée Carnavalet in Paris (photo by Pierre-Yves Beaudouin, via Wikimedia)

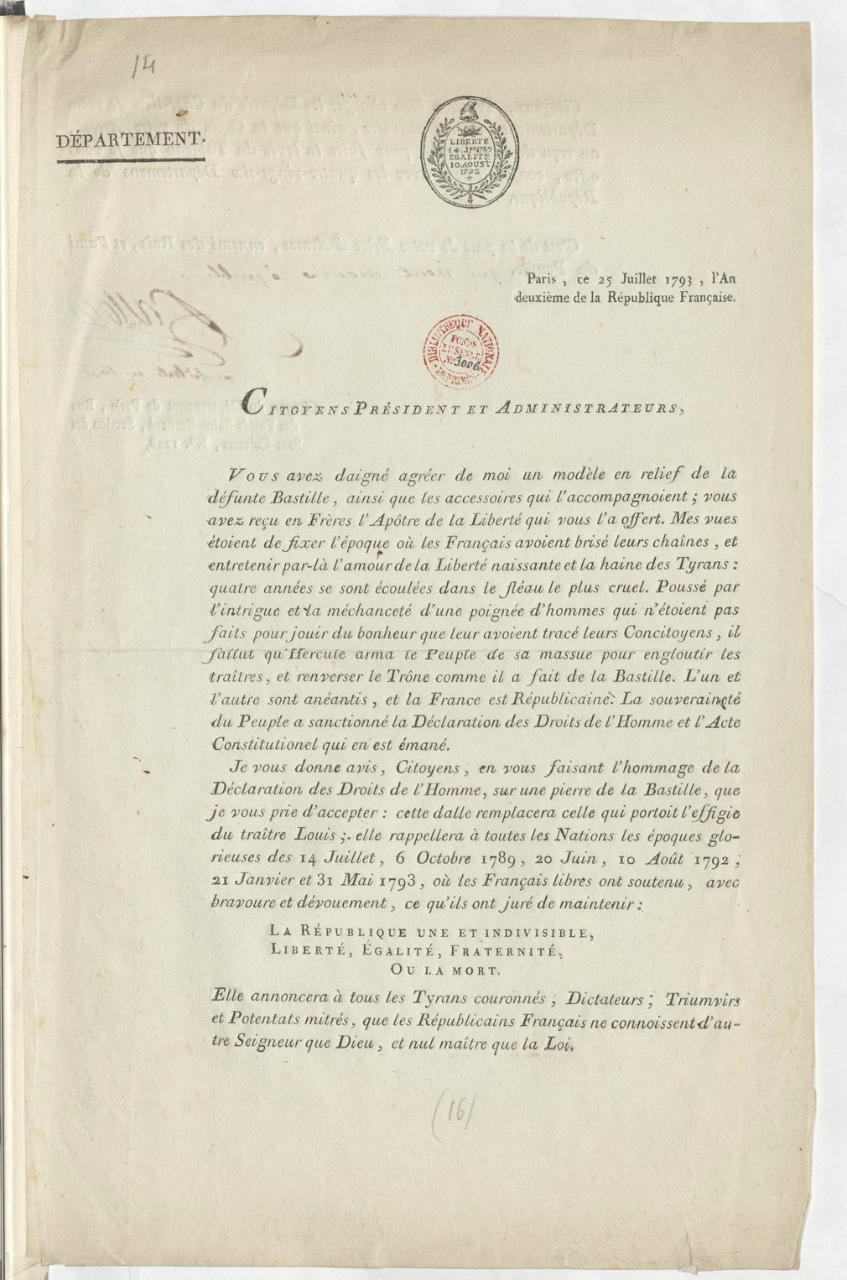

Letter signed by Palloy to recipients of the Bastille models (July 25, 1793) (via Gallica)

Miniature Bastille made from a piece of the prison at the Jeu de Paume at Versailles (via Wikimedia)

Model of the Bastille at the Musée Carnavalet (photo by Shadowgate, via Wikimedia)

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου