But the Air Force intervened

by JOSEPH TREVITHICK

When

one thinks of the U.S. Army, one generally doesn’t think of squadrons

of jets flying around the battlefield. But at the height of the Cold

War, the ground combat branch had its sights set on buying a fleet of

jump jets.

Though

the Pentagon turned the U.S. Air Force into a separate service shortly

after World War II, its ground-pounding cousins remained interested in

helicopters and other flying machines. A decade later, Army aviators

were hard at work with aircraft makers to cook up special craft that

could land and take off like helicopters, but fly like normal planes.

“While

the 1947 National Security Act created an independent United States Air

Force, this did not halt the expansion of Army organic aviation, or the

Army’s increasing use of the helicopter,” Dr. Ian Horwood wrote in Interservice Rivalry and Airpower in the Vietnam War.

“[But] in the early 1950s, such ‘convertiplanes’ appeared to offer more

potential for Army surveillance and air mobility tasks than

helicopters.”

By

1950, the idea of combining features from helicopters and traditional

aircraft was hardly new. Spanish engineer Juan de la Cierva invented the

autogyro, which blends a free-spinning rotor and a conventional

forward- or rear-mounted engine, nearly three decades earlier.

As

world settled into the Cold War, major air arms became fascinated by

the idea a jump jet that wouldn’t necessarily need a long runway. During

World War II, Allied forces bombarded Nazi Germany’s air bases and

limited the Luftwaffe’s ability to fight back.

On

both sides of the Iron Curtain, military commanders realized that

nuclear war would only speed up the destruction of normal airstrips. By

the time Berlin fell, Hilter’s weaponeers had already started work on

various alternatives, such as rocket planes that could shoot straight up

into the sky from a small launch rail right into enemy bomber

formations

.

.

However,

deadly surface-to-air missiles steadily replaced the need for these

sort of defensive planes. Still, American, British, German and Russian designers kept working on potential designs.

For

the Army, a covertiplane would allow aviators to keep the aircraft

close to the front lines and the soldiers they would undoubtedly be

supporting on the ground. Troops would not have to capture enemy

airfields keep the jump jets nearby.

But

the fledgling Air Force saw the sky as their domain. The flying branch

repeatedly opposed the ground combat branch’s research.

In

1949, both services agreed to the Bradley-Vandenberg Agreement, which

limited the weight of any Army planes to less than 2,500 pounds without

any fuel, ammunition or weapons under the wings. The flying branch hoped

this would kill the ground combat branch’s aspirations.

Instead, Army leaders claimed that their hybrid aircraft did not fall into this category. The Air Force was apoplectic.

After

three years of complaints and negotiations, the Pentagon imposed a new

deal that doubled the minimum weight for Army planes. This time, the

ground combat branch succeeded in getting a formal exemption for

convertiplanes.

While

the bickering continued, the Army never stopped its work on various

flying machines, helicopters and jump jets. By 1966, the ground combat

branch was testing more than 30 different kinds of crafts from futuristic jetpacks to “flying jeeps,” according to a contemporary fact sheet.

The

litany of projects also included two types of convertiplanes. While

plane makers Lockheed and Ryan Dubbed their unarmed prototypes “research

planes” to try and fend off any Air Force objections, the Army saw the

aircraft as integral to their future battle plans.

Externally,

Lockheed’s XV-4 Hummingbird looked very much like a small jet fighter

bomber. The plane could take off vertically by venting the engine

exhaust through nozzles in the underside of the aircraft. To help

produce more power in vertical flight, the top of the fuselage would

open up so the engines could pull in additional air.

In

contrast, Ryan’s XV-5 Vertifan had two traditional engines to power the

plane like any other jet aircraft. But when hovering, a valve would

open and force exhaust to drive three, powerful lift fans.

At

4,995 pounds, the original XV-4 was just under the Pentagon-imposed

restrictions for conventional Army planes. The XV-5 weighed nearly twice

as much.

Both

aircraft were much faster than Army choppers. The Hummingbird could get

to a top speed of over 500 miles per hour. The Vertifan topped out at

nearly 550 miles per hour.

Unfortunately,

neither design proved to be particularly functional — or safe. On June

10, 1964, Lockheed’s first prototype crashed, killing the pilot. Less

than a year later, test pilot Lou Everett died when the initial Ryan

model went down as the Army showed the plane off to the public.

In

both cases, the complicated engine arrangements proved to be

under-powered and unstable. In 1965, Army weapon testers recommended

Ryan make five “mandatory” fixes and suggested another 11 more

“desirable” changes, a preliminary review stated.

The

evaluators complained about overheating in the XV-5’s cockpit, engine

and fan ducts, sensitivity to gusts of wind while hovering and other

problems. Lockheed and Ryan both rebuilt their prototypes to try and

solve the issues.

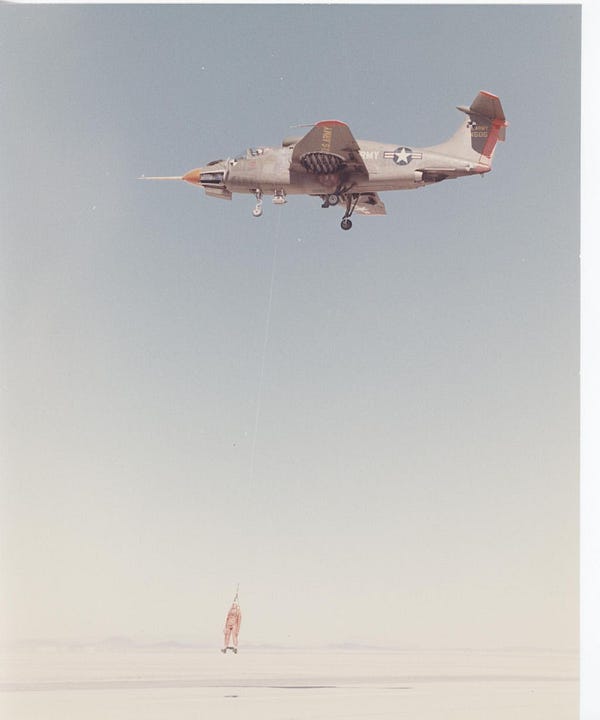

In

addition, Ryan proposed turning their type into a rescue plane. With a

hatch in the bottom of the fuselage and a hoist, crews could reel in

wounded troops like a helicopter, but race much faster to the nearest

battlefield hospital.

The

problems continued in dramatic fashion. During a mock rescue mission in

1966, the lift fans on the XV-5 sucked up the dummy injured soldier.

With the mannequin in the motor, test pilot Bob Tittle lost control and

died in the resulting crash. Ryan managed to repair the damage so tests

could continue.

Three

years later, the remaining XV-4 smashed into the ground in yet another

incident. Harlan Quamme safely ejected, becoming the only test pilot to

survive an accident in one of the jump jets.

By

that point, the Army was losing its battle for its own jets. The

Pentagon and lawmakers repeatedly sided with the Air Force. The ground

combat branch had lost the right to arm its scout planes and its CV-2

propeller engine cargo planes.

In

the early 1960s, the service had tried and failed to get its hands on

two British Hawker Siddeley P.1127 prototypes. Between 1964 and 1965,

the service had managed to squeeze into itself into a test partnership of these planes along with Germany and the United Kingdom.

But

after the evaluation ended, the Air Force took over the experimental

XV-6s — and promptly got rid of them. The Germans ultimately dropped out

of the program. However, with continued interest from the U.S. Navy and

the British military, Hawker Siddeley pushed ahead, leading to the

iconic Harrier jump jet.

In

1971, the U.S. Marine Corps put the refined AV-8 Harrier into service.

The same year, the Army’s jump jet dreams finally came to an end.

Today, the surviving XV-5 now sits outside at the U.S. Army Aviation Museum at Fort Rucker in Alabama.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου