youtube.com/watch?v=doAGwslV6VI

youtube.com/watch?v=doAGwslV6VI

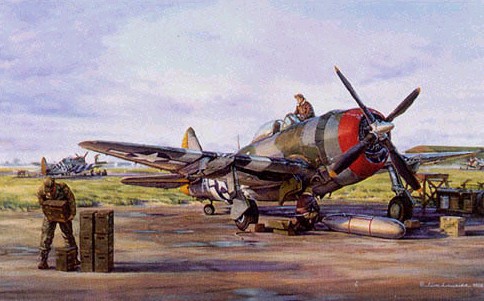

Not commonly known but the F-47 Thunderbolt had a last hurrah with the French fighting in Algeria in the 1950s...

Since we cannot replace our fighters we darn well better disperse, camouflage (in the air and on the ground) and harden them so they don't get caught on the ground in the face of an enemy "Bodenplatte" type attack.

And of course, we need a P-47/IL-2/Stuka equivalent for MAS ASAP.

The Air War Nobody Told You About

P-47 Thunderbolts on the Continent of Europe, 1944-45 Combat Aircraft, March 2004

by Robert F. Dorr and Thomas D. Jones

The P-47 Thunderbolt evoked fierce loyalty from pilots who flew it, but today one group of P-47 veterans is bitter. Thunderbolt veterans who fought on the European continent in the final year of World War II feel that their contribution has been forgotten. "People don't know we were there," said retired Col. James L. "Mac" McWhorter. "Air-to-ground action wasn't glamorous, and it attracted very little attention."

Today, war often appears clean and efficient when viewed on television screens.

But P-47 pilots know that combat can be dirty, gritty, and ugly. Consider, for example, the citation awarded to pilots of the 406th Fighter Group, for destroying a column of German vehicles attempting to escape advancing Allied forces near Chateauroux, France:

"Thirty-six P-47's of the 406th Fighter Group took off on September 7, 1944 at 15:05 hours and raced south of the Loire River to find the road from Chateauroux to Issoudon clogged with military transport, horse drawn vehicles, horse drawn artillery, armored vehicles and personnel. Attacking this enemy concentration, at minimum altitude, in spite of accurate ground fire, the...pilots...made pass after pass until their bombs, rockets, and ammunition were expended. The road was blocked for 15 miles with personnel casualties, wrecked and burning military transport. More than 300 enemy military vehicles were destroyed in this attack alone."

The citation continues: "The group returned to home base, and after being refueled and rearmed in a minimum length of time, returned to the scene of the action. Before the enemy could reorganize and extract the remnants of his column, a further 187 vehicles, including 25 ammunition carriers, were attacked and destroyed. In spite of intermittent rain and the hazard of landing at night on a slick tar paper runway...."

Left out of the citation is the fact that Thunderbolts frequently strafed horse-drawn supply columns, leaving behind tangled, bloody carcasses. Thunderbolt pilot Tom Glenn says, "The horses were not our enemy, but our assignment was to prevent those columns from harming our troops." The gruesome sight sometimes made pilots physically ill---not what they expected when they signed up for pilot training starry-eyed about the beauty of flight. "No one would call this slipping the surly bonds," says Glenn, in a reference to the lofty words of the poem "High Flight."

Those who sat in P-51 Mustang cockpits at high altitude on escort missions to Berlin were able to savor a little of the joy of flying. But for Ninth Air Force fighter pilots, the job meant living in infantry-like conditions at snow-covered, mud airstrips on the Continent and flying low-level strafing and bombing runs---"not clean, not comfortable, and certainly not glamorous," says Glenn, "but necessary...."

Low-Level Hell

To a man, the dozen P-47 pilots interviewed for this article agree that they might not be alive today had they been flying the P-51 instead of the rugged, eminently survivable Thunderbolt. As Americans learned later in Korea, the under-fuselage cooling system of the P-51 made the Mustang vulnerable to gunfire at low altitude, even small-arms fire from infantry rifles. The Mustang was a feisty filly at higher elevation, but the Thunderbolt offered the best chance to stay alive down low where the metal was flying around.

MYSTERY: Where were all the 15, 683 x F-47s when the 1950 Korean war unfolded? Surely their fuel hoggish nature would have been offset by their ruggedness to enemy fire...want to see a movie on F-51 vulnerability during ground attack in the Korean War, watch the Rock Hudson movie, "Battle Hymn".imdb.com/title/tt0050171/

Perhaps USAF fledgling fighter pilot narcissism so to it that the thousands of F-47s were scrapped or given away quickly in favor of the sexier F-51s....that with liquid-cooled engines were extremely vulnerable to ground fire later on in the Korean war...

Not for nothing, the Farmingdale, N. Y. manufacturer of the Thunderbolt was called the "Republic Iron Works" and had a reputation for building fighters that were big, roomy, and survivable. One P-47 returned to its European base with body parts from a German soldier embedded in its engine cowling. Another landed safely riddled with 138 holes from bullets and shrapnel.

P-47s rolled out of American factories in greater numbers than any other U. S. fighter, ever. There were 15,683 x P-47s, a figure that compares to 15,486 x P-51s, 13,143 P-40 Warhawks, and 10,037 P-38 Lightnings. But while the ubiquity of the Thunderbolt is undeniable, P-47 pilots are accustomed to being slighted. In an appalling gaffe, the U.S. National Air and Space Museum did not have a P-47 on permanent display until the omission was rectified in late 2003 at the museum's new Udvar-Hazy Center at Dulles Airport, Washington, D.C. The Museum has long been the owner of a pristine, Evansville-built P-47D-30-RA (44-32691) but for many years had it loaned out to the Museum of Aviation at Warner Robins, Ga.

For men caught up in a down-and-dirty conflict on the European continent, it was indeed fortunate that the Thunderbolt existed at all---especially since the aircraft emerged from a conversation aboard a railroad car traveling between Dayton, Ohio, and New York in 1940. Republic Aviation's chief designer Alexander "Sasha" Kartveli, Army Capt. Marshall "Mish" Roth, and Republic's C. Hart Miller were coming back from a Wright Field conference, where they had learned that Republic's two fighters then being proposed to the Army, the P-44 Rocket and the XP-47 lightweight fighter, failed to give Army Air Corps the performance it wanted.

The trio discussed ways to exploit the best of what they had already -- the 2,000-hp. Pratt & Whitney R-2800 Double Wasp 18-cylinder, twin-row air-cooled engine they had selected for the XP-47, a superb cockpit design, and the proven airfoil and wing of the P-43 Lancer and the proposed P-44. They talked of building on these positive features to create a more robust fighter. Kartveli jotted notes on the back of an envelope, giving rise to the myth that the Thunderbolt was designed this way.

The first XP-47B---a wholly different aircraft from the never-built XP-44 and XP-47---took to the air on May 6, 1941, with Republic's Lowery Brabham at the controls. Built around its massive engine and the extensive ducting system for its turbosupercharger, the new fighter dwarfed its competitors. Early in its career, pilots dubbed the aircraft the "Jug" because of its portly shape. Contrary to accounts published much later, the nickname had nothing to do with the P-47 being a juggernaut, although it assuredly was one.

By the time the Allies landed in Europe, the "razorback" configuration of early Thunderbolts (and the automobile-style door of the prototype) was giving way to the bubble canopy found on late P-47D models. The typical P-47D flown on the Continent by Ninth Air Force pilots had a 2,535- R-2800-59W radial, a 17,500-pound takeoff weight, and eight .50-caliber (12.7-mm) Browning M3 [heavy] machineguns packing 250 rounds each.

Formidable Fighter

Fifteen fighter groups, 45 squadrons, and about 14,000 pilots and maintainers made up the Thunderbolt force on the continent. For these men, air-to-air combat---normally the way a fighter pilot attained glory---was secondary. As 2nd Lt. Leslie Boze of the 365th Fighter Squadron described it, "We felt our efforts would help to win the war."

By D-Day, June 6, 1944, Thunderbolts were pouring from factories faster than pilots could fly them away. They were soon arriving in the combat zone in natural metal finish, devoid of the olive-drab camouflage scheme in which the Thunderbolt began its operational service. They were decorated with caricatures and names---the term "nose art" had not yet been invented---that reflected the personalities of their pilots. McWhorter's P-47 was named "Haulin' Ass." Boze's was "Blonde Trouble."

Bob Hagan of the 365th Fighter Group, the "Hell Hawks," remembers that the air-to-ground war seemed "very personal," as when he engaged in a one-on-one contest with a German gunner while strafing troops in a forest. Hagan remembers the gunner tracking him through each pass in the contest of survival, he did his best to outwit his adversary by jinking, then returning to make another strafing run. The war at low altitude could be very personal but on that occasion Hagan doesn't know whether he got the gunner after two or three passes. Looking down through trees, snow, and mush, he couldn't tell.

"I felt comfortable handling the Jug," Hagan said. "It was big and heavy [with a gross weight of 19,400 lb. in the P-47D-25 model], but it never felt that way." Hagan recalled that the P-47 created less engine torque than the P-40 Warhawk flown during training, that the Thunderbolt took off smoothly, and that acceleration forces rarely exceeded the 3 or 4 Gs encountered for a few seconds when coming off a target.

Hagan said the pilot did not feel the bombs coming off during a high-speed dive. He said Thunderbolt pilots typically closed to about 200 yards before opening fire on a ground target. "You could see smoke trailing from other Thunderbolts when they were firing. You sensed a vibration when the guns were being fired, but no big shaking." Thunderbolt pilots believed their eight guns gave them enormous firepower. Gun camera film supported that view.

Hell Hawk

While the emphasis was on air-to-ground fighting, Hagan and his fellow P-47 pilots faced German fighters as well. On October 21, 1944, the 365th FG "Hell Hawks" took off from Chievres, France on a sweep over the German frontier. The top cover unit, the 386th Fighter Bomber Squadron, spotted bogies at 22,000 feet---a flight of 30 Focke-Wulf Fw-190s. Diving out of the sun at the enemy formation, the Thunderbolts forced the -190's to break earthward, straight into the sights of the group's other two squadrons. In the huge, swirling air battle that followed, the Hell Hawks knocked down twenty-one of the enemy fighters.

Hagan was flying wing on the 386th's commanding officer when they slashed through the German flight. After a few minutes in the melee, Hagan's engine began smoking and his Thunderbolt lost power. He didn't think he'd been hit. Apparently, he had run into his leader's spent .50-caliber shell casings. Hagan dropped out of the action and turned toward Allied lines.

With his heavy Thunderbolt in a stable but steep glide, he knew the chances were slim that he'd make it to an emergency field. Hagan unbuckled his harness and squatted on the seat in preparation for bail-out. The young lieutenant hesitated: he was almost certain to be captured if he abandoned the plane so far east. Deciding to take his chances with his ship, he sat back down, strapped in, and willed the P-47 towards the front line and safety.

With a sudden jolt, the Thunderbolt's engine finally seized. Beyond the motionless prop, Hagan could see hilly terrain with small woodlots below. Too low to bail out and with no sizable pastures at hand, his only option was a forced landing. Heading into a small clearing, he realized his final glide would carry him right into a clump of trees at the far end. He banked as much as he dared in an attempt to swing wide of the timber looming ahead.

It was too much to ask of the heavy Jug. The Thunderbolt's right wing stalled and dipped toward the earth rushing by. Catching a wingtip, the big fighter cartwheeled across the pasture, in the process shedding the radial engine, both wings, and the tail section. As the P-47 tore itself apart, Hagan tumbled with the wreckage, protected by the sturdy cockpit structure. As the wreckage slid to a stop on the Belgian turf, the impact slammed his head against the instrument panel cracked several ribs. He was clear-headed enough to crawl from the crumpled cockpit, Hagan headed for a GI and a Jeep he'd spotted on a road bordering the pasture.

After making a successful, if painful, dash across the clearing, an exasperating Hagan asked the GI why he hadn't driven over to pick him up in the Jeep. "Because you landed in a minefield," the GI deadpanned.

The injured pilot's luck continued to hold. After going only two hundred yards, he was rushed by GIs who hustled him back through their lines to an aid station. He had crash-landed just 400 yards from the front, near Athus, Belgium. In eight weeks, Hagan was back flying combat in a new P-47. A few months later, hit by flak after strafing a Luftwaffe airfield at Leipzig, Germany, Hagan bellied in near the Ruhr Pocket and again evaded capture. (Hagan went on to a lifetime of many other aviation achievements, including making the first flight of the Cessna T-37 Tweet trainer, aircraft 54-716, on October 12, 1954).

Air Action

While the Thunderbolt's primary fight on the Continent was an air-to-ground war, there was aerial action as well.

1st Lt. Leslie Boze of the 365th Fighter Squadron was element lead in his Thunderbolt on a typical ground attack mission over Germany when he was drawn into an aerial battle. A Lt. Jones (first name unknown) was leading the flight, followed by 1st Lt. Tom Easterling. A pilot named Gallagher flew on Boze's wing in the second element.

Spotting a Wehrmacht truck convoy, Jones led the flight down in a tight spiral for a strafing attack. Jones, in the lead, opened fire with his eight .50-caliber [heavy] machine guns as Easterling curved in behind him.

Flak began to rise from the German convoy to meet the onrushing attack. In just a few seconds the four P-47's were caught in a vicious crossfire, and Easterling caught the worst of it. His plane staggered under the impact as Gallagher shouted over the radio, "Tom! The son-of-a-bitch is on fire! Get the hell out of it!" Easterling barely managed to bail out of the burning fighter. He opened his parachute just seconds before hitting the ground. Severely injured, Easterling struggled through pain and imprisonment until liberated from a POW camp at war's end.

Boze and Gallagher had barely digested the sight of Easterling's plane being hit when they caught sight of a pair of Bf-109s, boring in on their element. Boze pulled off the convoy and headed straight for the nearest -109. The Messerschmitt, a head-on silhouette, opened up with its 20mm cannon; Boze had to wait until his fifties came into effective range. The -109's cannon rounds came streaking by his canopy like a string of glowing white golf balls. Now Boze had the enemy in range, and he touched the trigger. The eight .50's reached out to the Messerschmitt and staggered it. Boze could see his armor-piercing incendiary rounds hitting home, sparkling over the wings and cowling of the onrushing fighter. The German pilot still came on, nose-to-nose, in a deadly game of chicken. Still scoring strikes on the -109, Boze held the trigger down as the two fighters came together. In the last split-second, the German pulled up and whipped over the top of Boze's Thunderbolt, a near-miss so close that he heard the roar of the -109's Daimler-Benz engine.

Looking back over his shoulder as he turned slightly, Boze caught sight of the enemy, smoking and slipping toward the wooded terrain below. The German slammed into the ground in an oily fireball. There was no parachute.

Winter War

Today, it is convenient to think of the war as a straight-line march of victories that led to Germany's defeat. It is also easy to think of the air war without considering what was happening on the ground.

Both approaches are too simple. The story of P-47 Thunderbolt pilots on the Continent ran parallel to the saga of combat Soldiers on the ground. In fact, pilot one pilot referred to the Thunderbolt as "a foxhole in the sky." The landings at Normandy, the slugfest in the Falais Gap, the Battle of the Bulge, and the final victory in Europe saw ground Soldiers and P-47 pilots fighting together.

Perhaps the best examples came in one of the largest battles ever fought (perhaps with the sole exception of Kursk, on the other front). A furious attack by German armies on December 16, 1944, surprised Allied troops in the Ardennes, a forested plateau in northern France that been the scene of earlier fighting in both world wars. The Germans opened the assault along a 50-mile front, initially with twenty-one infantry and armor divisions. They called it the Ardennes offensive; Americans called it the Battle of the Bulge.

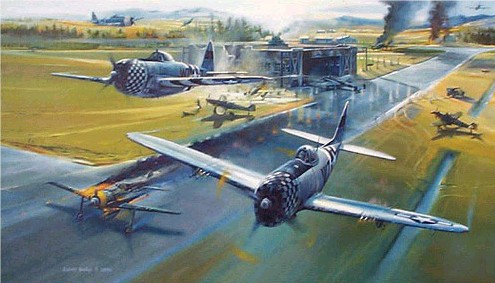

Two weeks later, on January 1, 1945, the Luftwaffe launched Operation Bodenplatte (Baseplate), an air-to-ground effort against Allied airpower on the continent. Possibly 800 Luftwaffe aircraft struck about two dozen Allied airfields, including several where P-47s were based. By far the worst damage was inflicted at Y34 Metz-Frescaty airfield, where the 365th "Hell Hawks" suffered 22 x P-47s destroyed and 11 damaged. But in the course of destroying a total of 122 Allied aircraft on the ground, the Germans lost 200---and while only a handful of Allied personnel lost their lives, dozens of irreplaceable German pilots perished.

For a brief, shining moment, the Luftwaffe apparently believed the New Year's Day air attack had been a giant success. Anyone could have been forgiven for concluding as much after seeing the twisted, blackened, smoldering wreckage of Thunderbolts at Metz. The story of a captured German pilot illustrates how the conclusion was the wrong one.

Cocky Captive

The German was arrogant. Never mind that his Bf-109 had been shot out beneath him. He had begun the new year by parachuting into the American airfield at Metz, now lit up by the fires of burning P-47 Thunderbolts---a sprinkling of bright torches amid the gray January gloom and the dirty white snow.

Initially at least, the air attack seemed a stunning setback to American pilots, maintainers, and support troops. In the months since D-Day, most had gotten accustomed to crude living conditions, lousy weather, and a war in which Thunderbolts harried the German army at low level where a lot of metal was flying around. They were not, however, used to being attacked.

U.S. Army anti-aircraft gunners managed to shoot down eight of the sixteen Messerschmitt Bf- 109s that came over that day, and the German pilot was now an American prisoner as a result. Yet he obviously believed that his side had inflicted a major blow. Standing inside 365th FG headquarters with Maj. George R. Brooking, commander of the 386th Fighter Squadron, the German jerked his thumb out the window at the burning Thunderbolts and said in perfect English, "What do you think of that?"

There was no denying the damage. But American industry had turned out nearly 100,000 warplanes in the calendar year that had just ended. Within a few days, Metz was in full operation again and factory-fresh Thunderbolts---brought down from a marshaling center near Paris---lined the ramp. There was no mistaking the corpulent shape of the distinctive P-47s.

Brooking went back to see the German, who was still being held at the base. Brooking pointed to the new planes and asked, "What do you think of that?"

It was time for a little humility. The German looked at the spanking-new aircraft, just arrived from a heartland

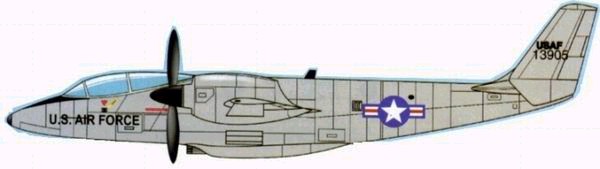

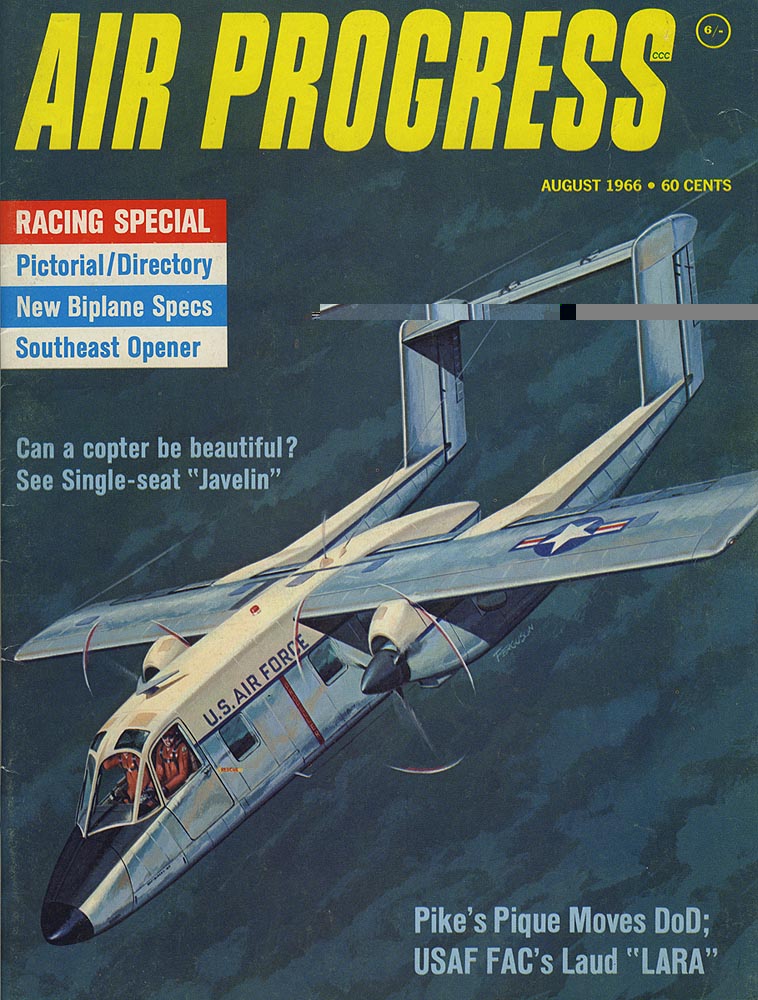

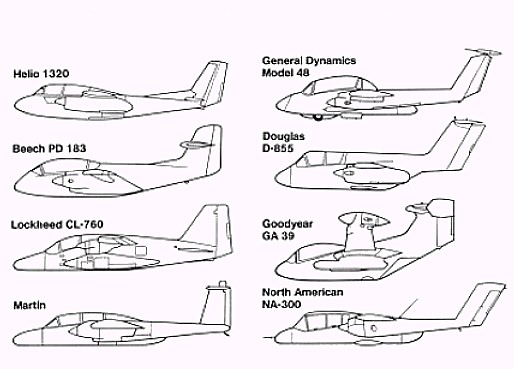

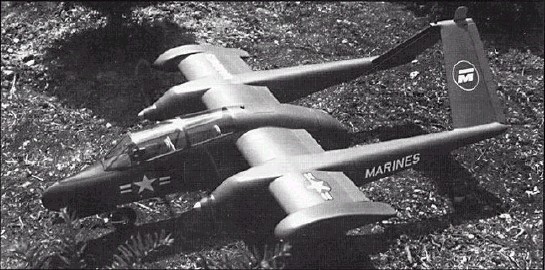

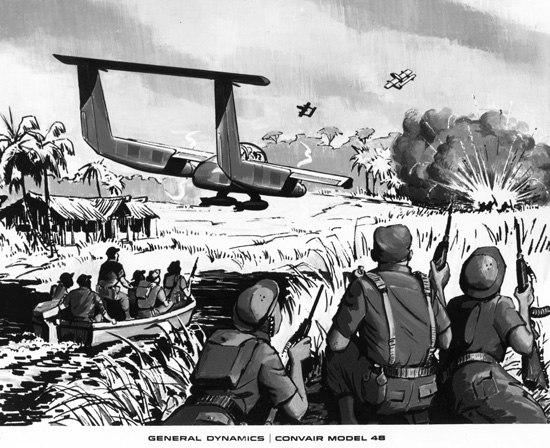

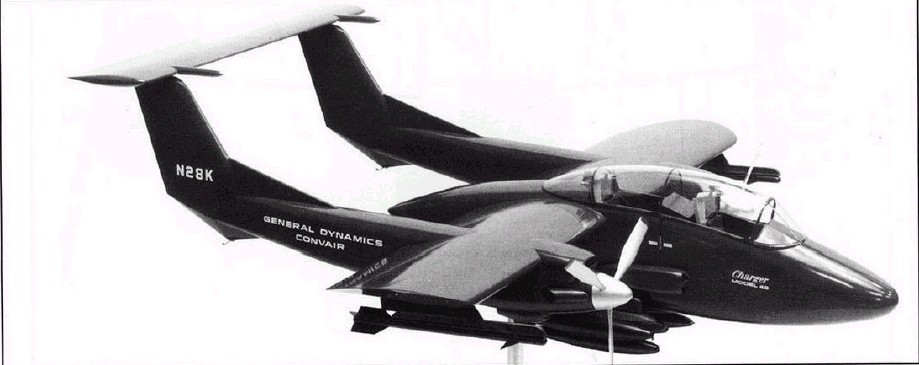

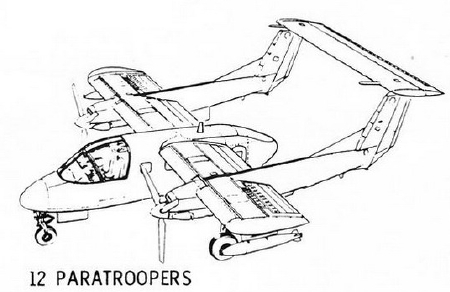

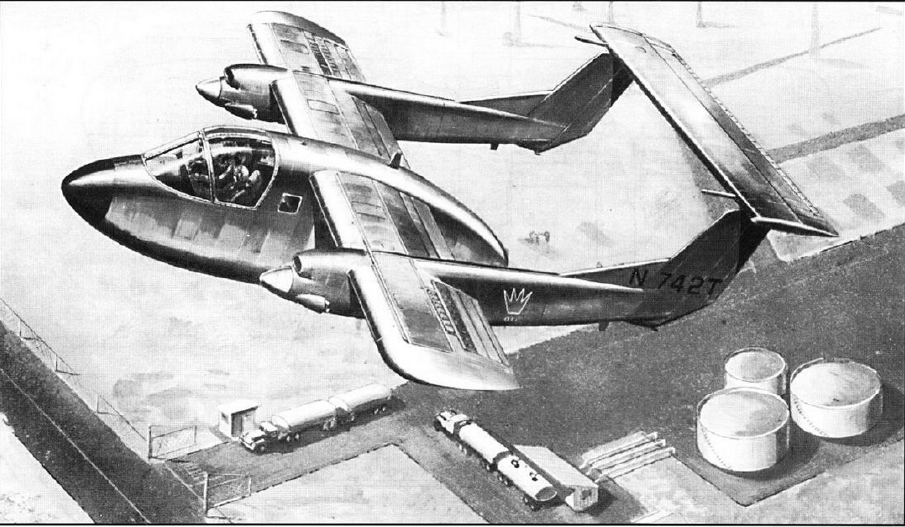

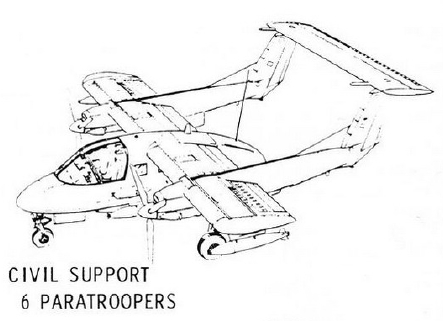

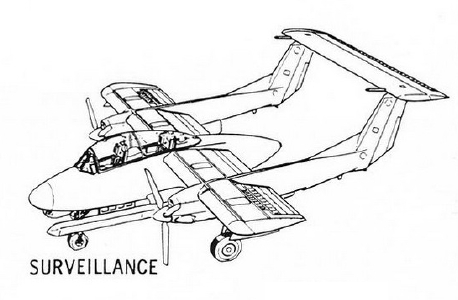

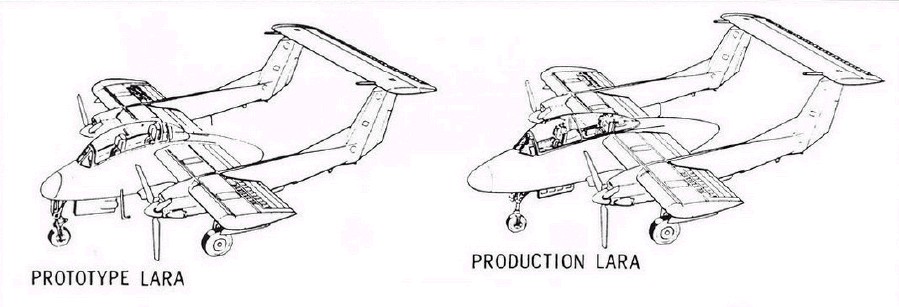

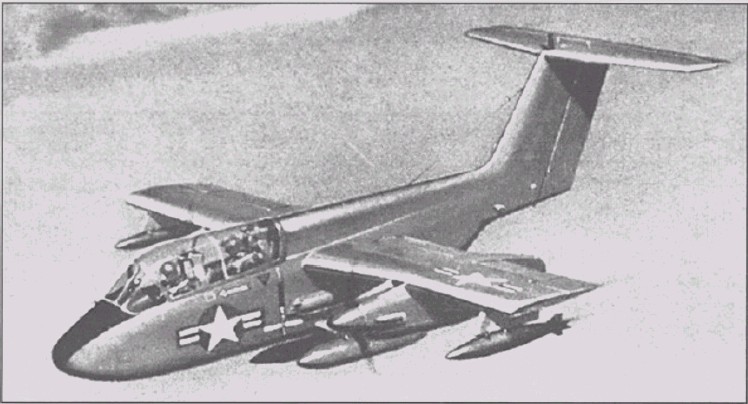

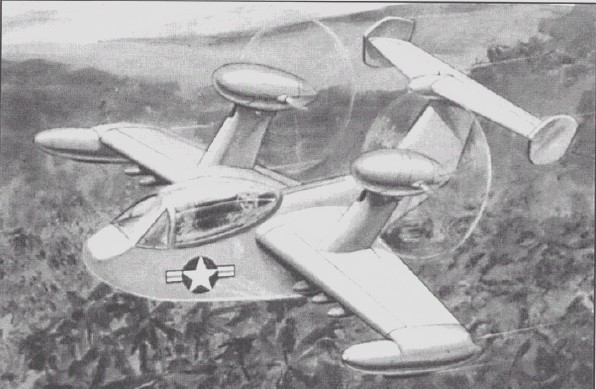

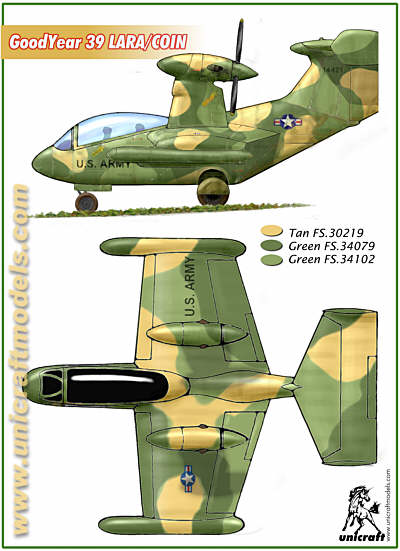

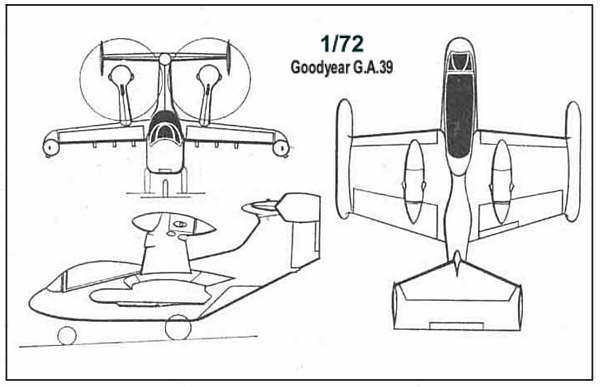

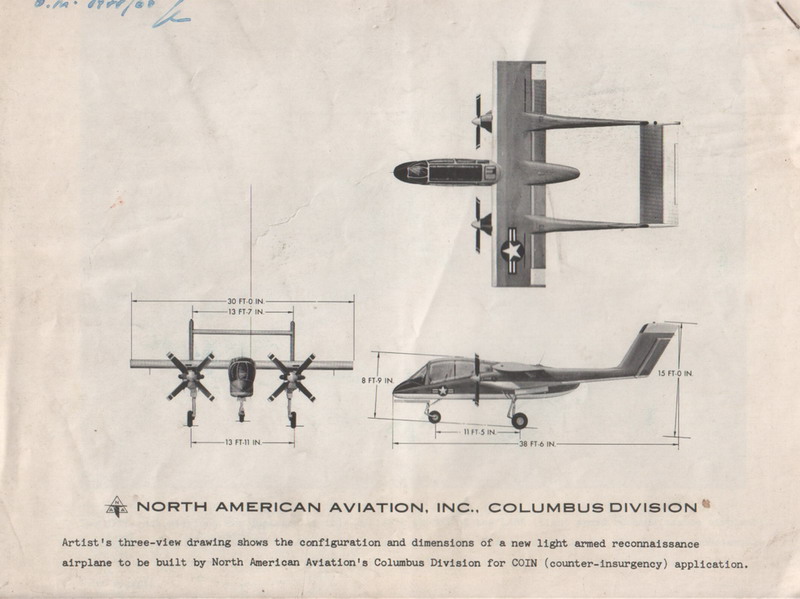

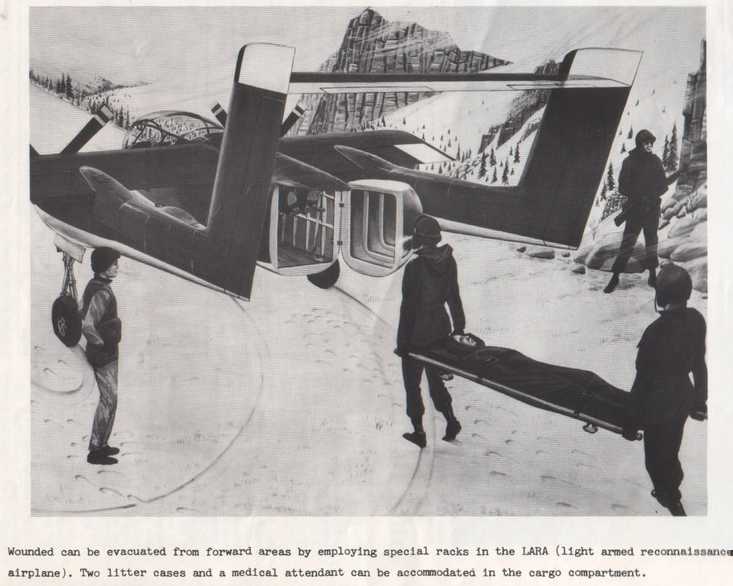

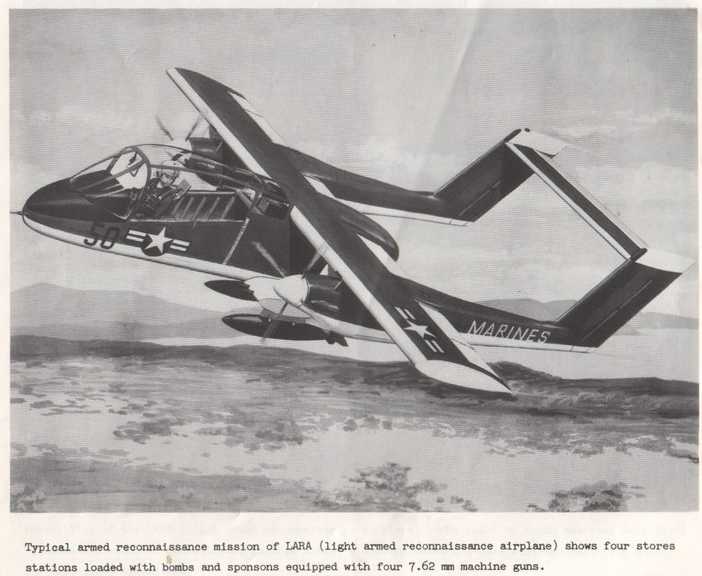

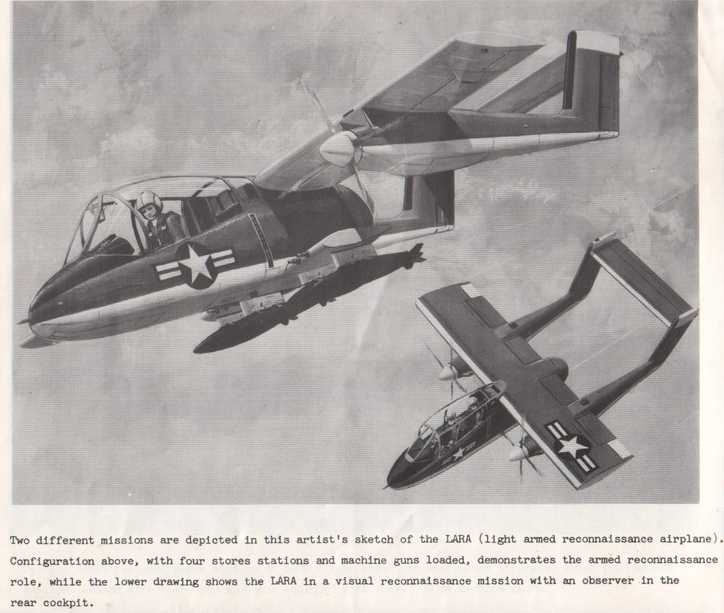

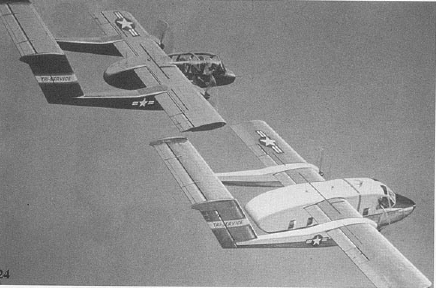

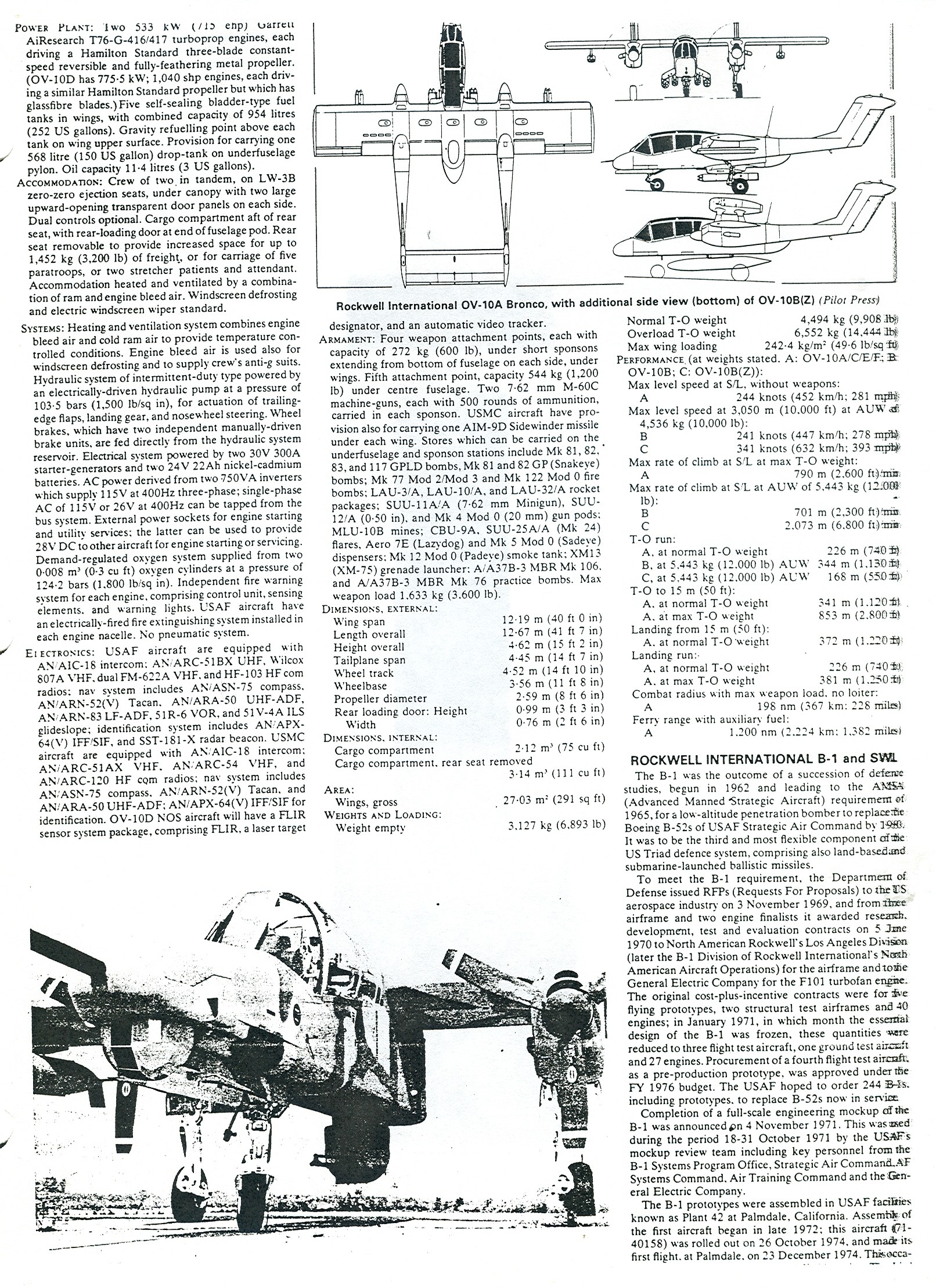

Fixed-wing "Killer Bees" better than armed Helicopters: DoD/USMC screws-up Light Armed Reconnaissance Aircraft (LARA) and gives us the need-an-airfield OV-10 Bronco

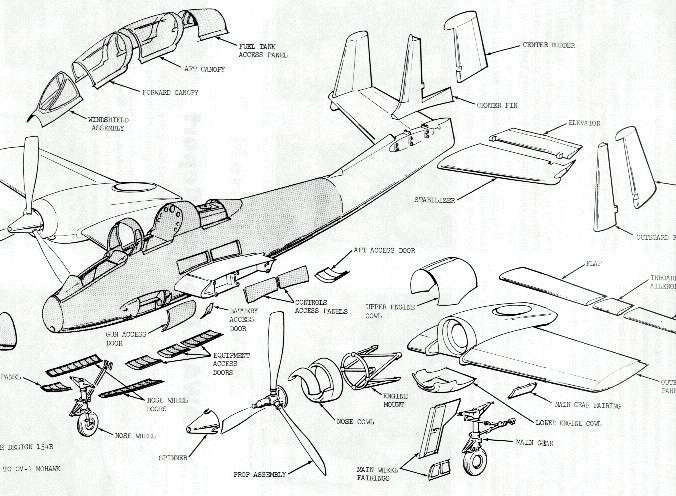

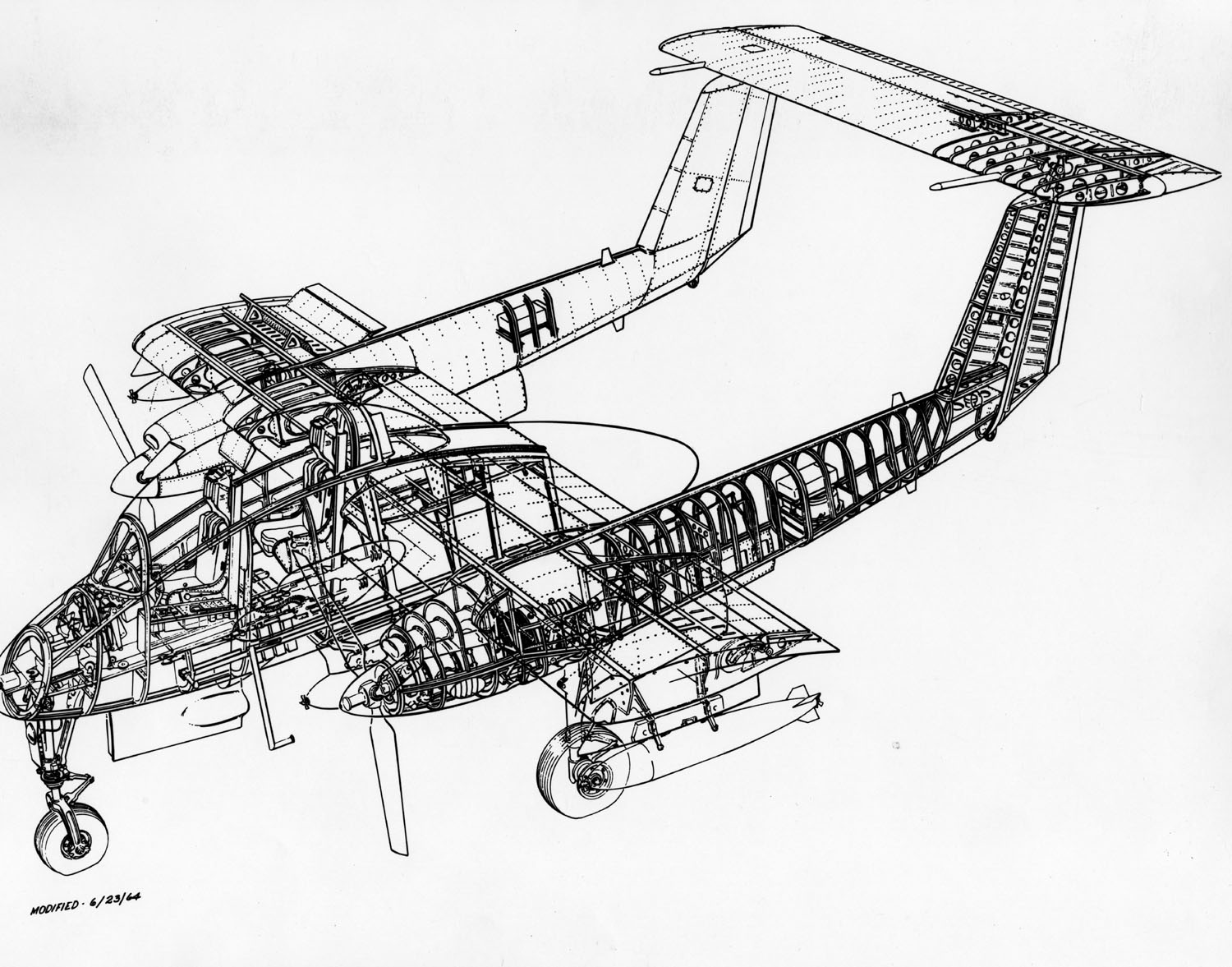

Boeing Model 147 = Tilt-Wing Mohawk

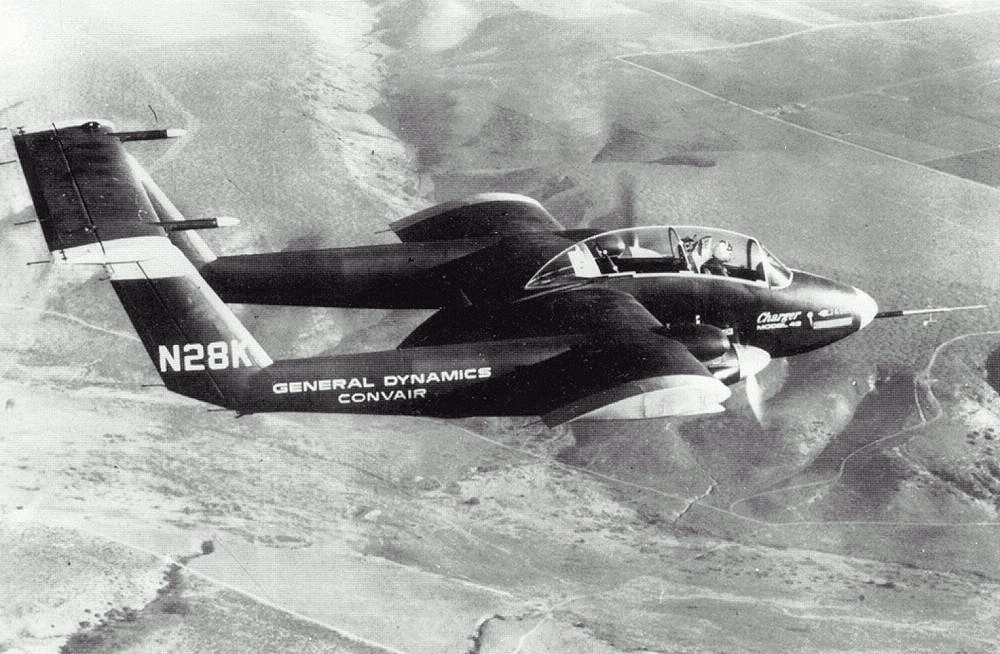

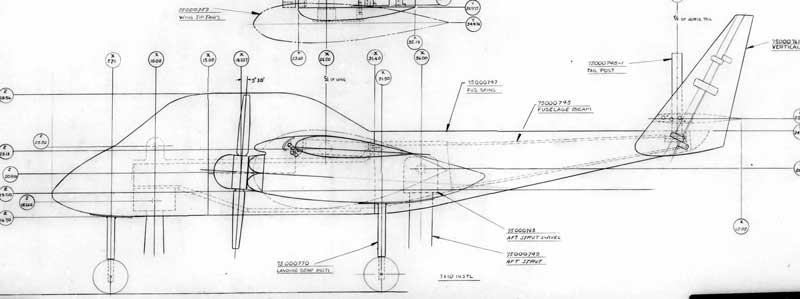

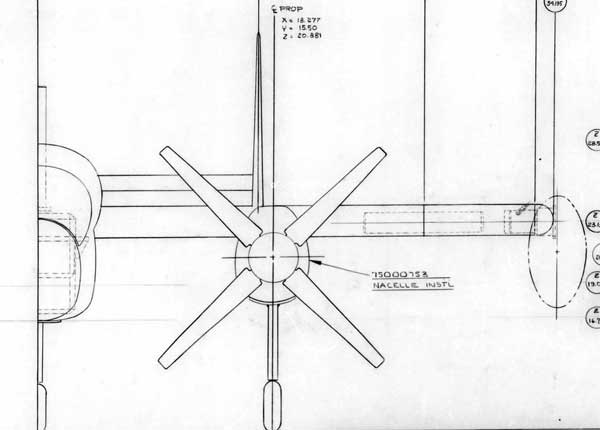

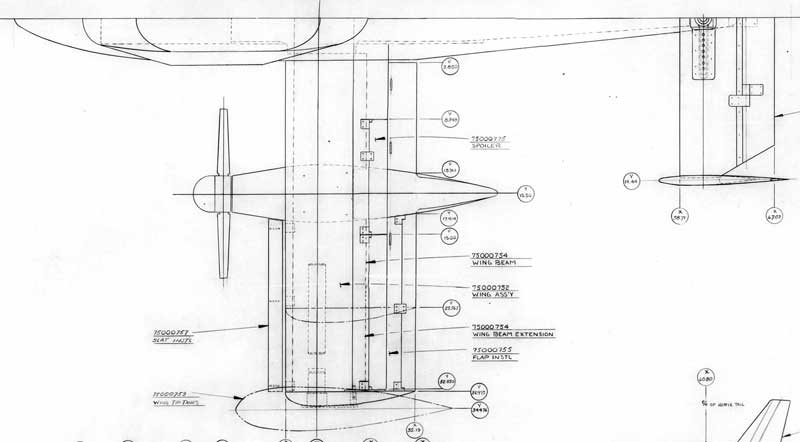

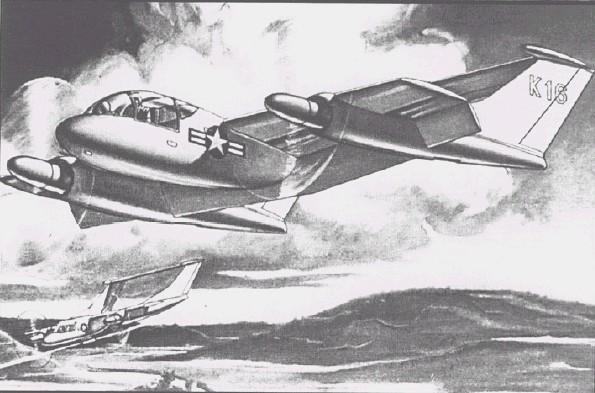

Proposed Charger float-equipped seaplane fighter

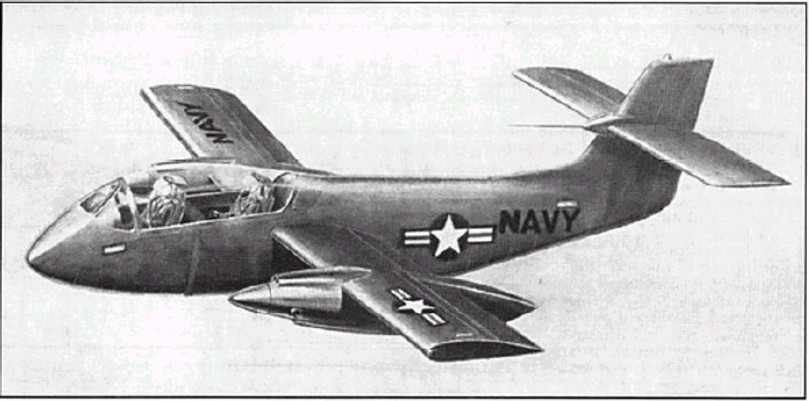

Grumman Model 340 Mohawk

The first candidate offered to the LARA competition was indeed a tandem-seat Model 340 Mohawk. This would be too much egg-on-the-face of the egotistical marines, so it was eliminated from the competition.

Click on Pics for Full-Sized Versions

Click on Pics for Full-Sized Versions

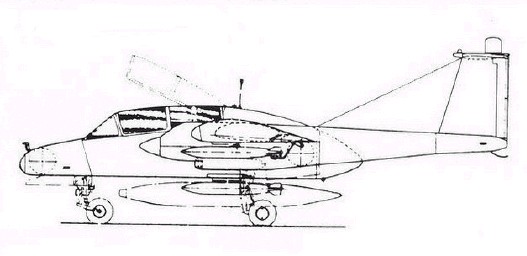

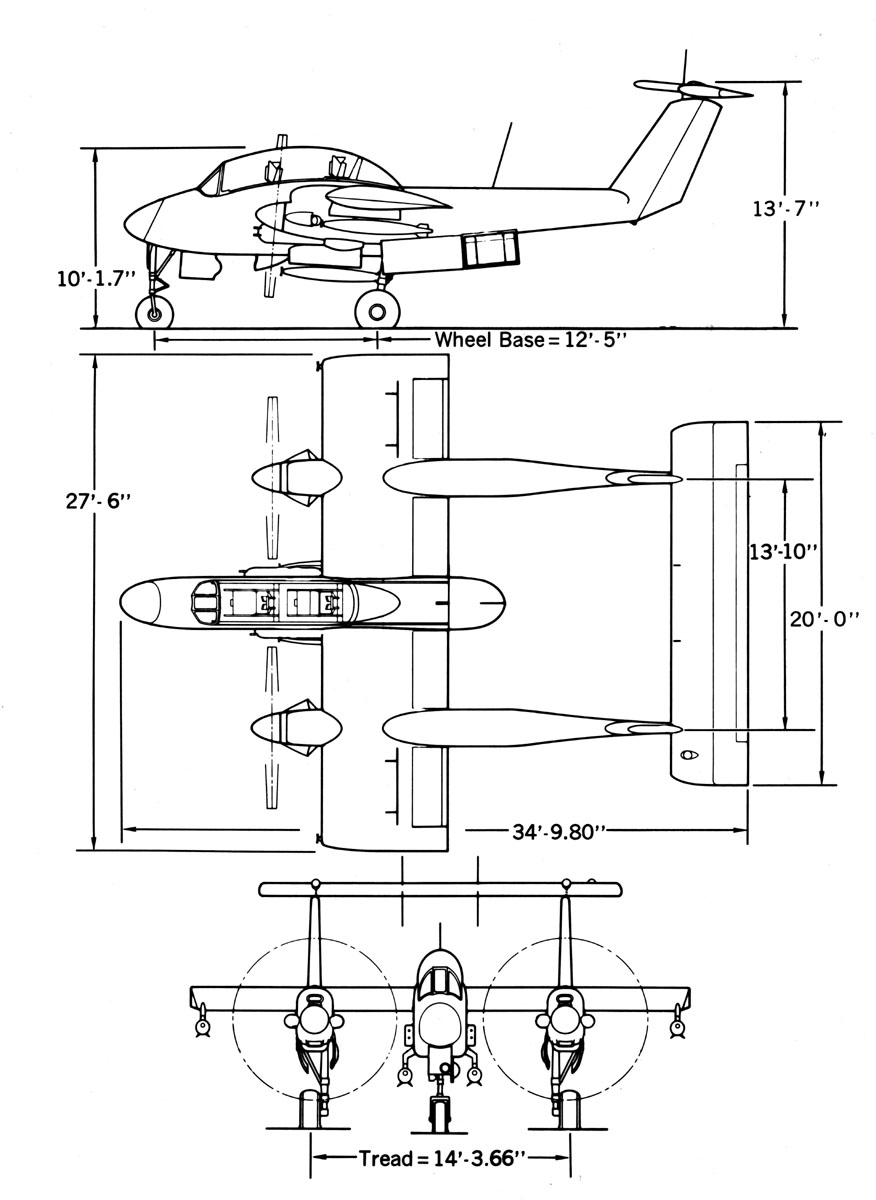

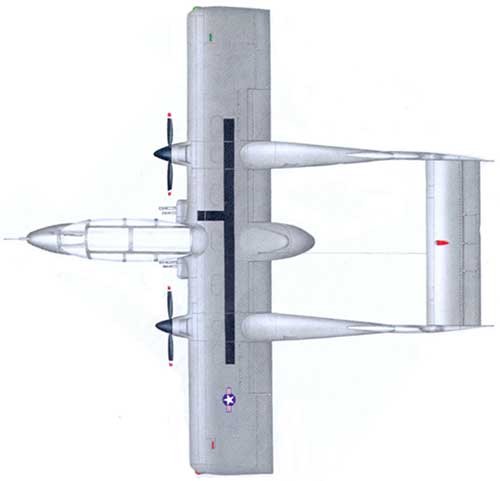

2-place Cabin mid-wing monoplane retractable landing gear

2 x 650hp P&W-Canada T74 (PT6) turboprops

span: 27 feet 6 inches wide

length: 34 feet 10 inches long

load: 6003# v: 319

range (ferry): 3000

ceiling: 21,300 feet

first flew: 11/25/64 (pilot: John W. Knebel)

9 foot contra-rotating props.

Produced in only 35 weeks from design, but lost out to North American OV-10, and it was the last complete aircraft to be built with the Convair nameplate. POP: 1 [N28K], destroyed in 1965 after its USN pilot successfully ejected at 100'.

Douglas Model 588

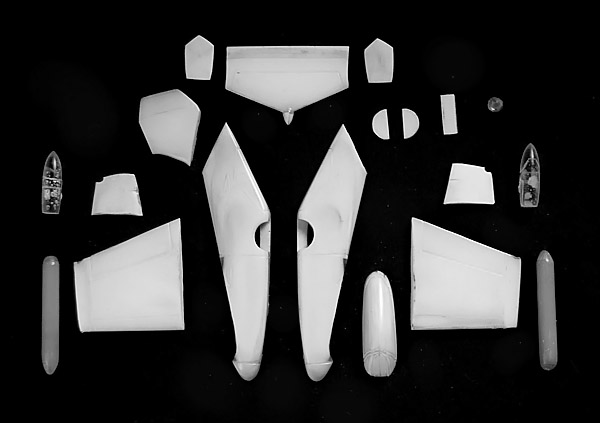

You can even build a 1:72 scale resin model of the GA-39!

You can even build a 1:72 scale resin model of the GA-39!

models.com

K.P. Rice

Volante Aircraft Company

2020 S. Susan Street

Santa Ana, CA 92704

(714) 545-0125

Email: KP@volanteaircraft.com

WWW: volanteaircraft.com

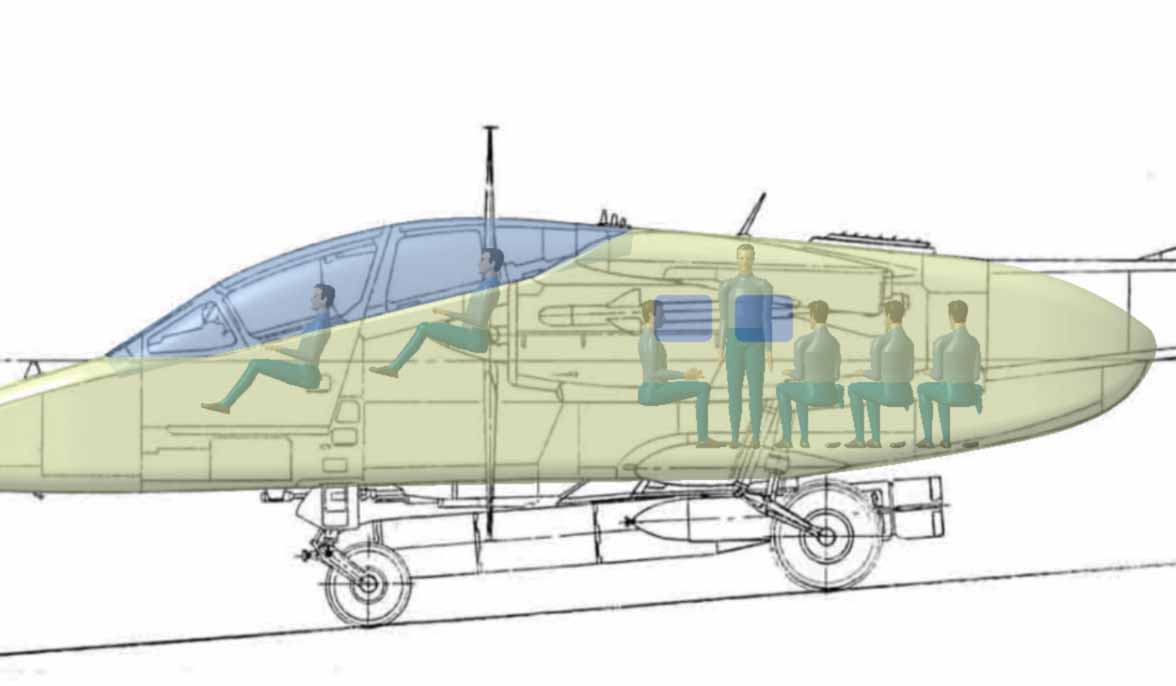

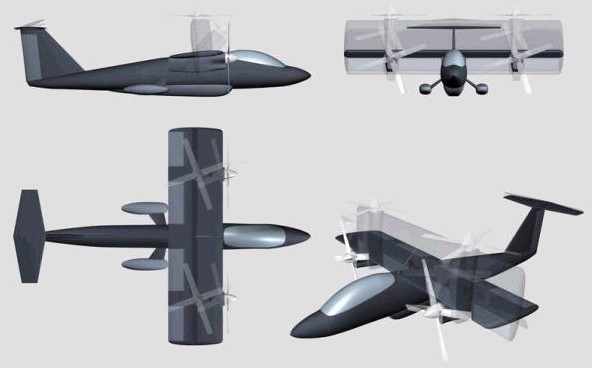

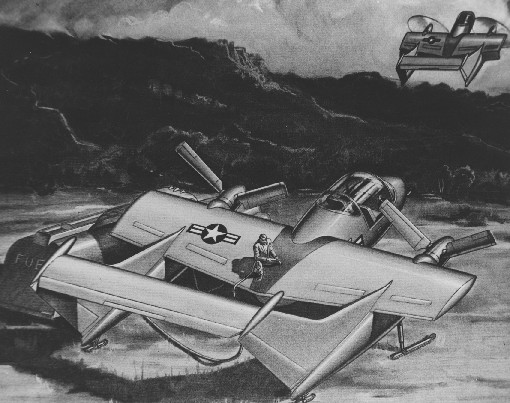

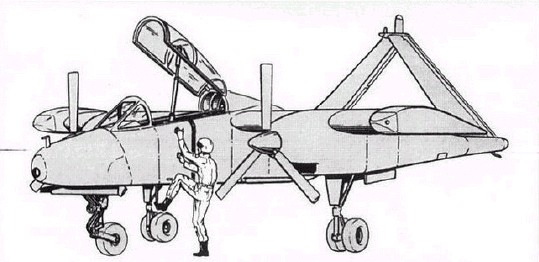

Rice wanted a fixed-wing observation/attack plane that could be CO-LOCATED with ground maneuver headquarters without need of an airfield via simplicity, small wingspan, and GROUND MOBILITY. Land and take-off anywhere--like Bush pilots in Alaska...

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου