Image credit: http://blog.modernmechanix.com/mags

I was wrong. I wanted to write about the Planet Satellite, because I thought it was an merely an obscure, attractive failure. However, the more I researched the Satellite’s story, the more bizarre it became. The

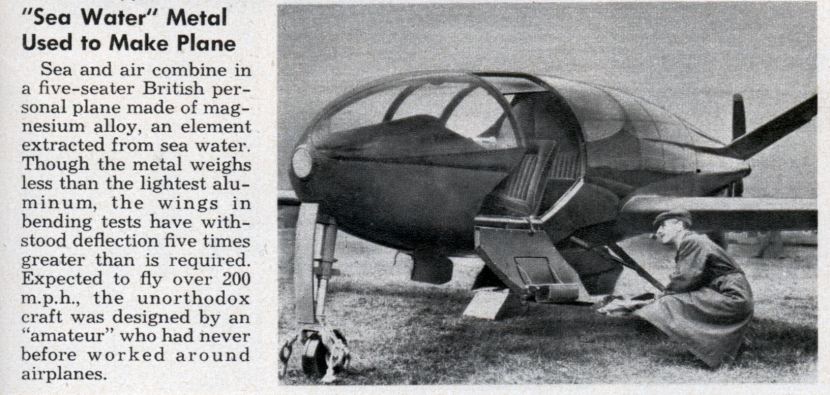

1948 Planet Satellite was an unusual and very beautiful aeroplane. Its

appearance suggested that Hergé had created it especially for Tintin to

steal. The aircraft was the shape of a tear-drop, with a butterfly

‘Y-shaped’ tail. Its ‘hygienically’ clean shape spoke of speed, progress

and a utopian future. The Satellite was a revolutionary design in

almost every way. It was a true monocoque design, for those unfamiliar

with the term- this does not mean it was single-penised (In fact, the

aircraft had no penis). A monocoque structure is supported by its

external skin, as opposed to using an internal frame. It is analogous to

an invertebrate (such as a beetle), whereas an animal with a normal

internal skeleton, like a person, is more like a traditional aircraft.

Though many aircraft are described as monocoque, strictly speaking the

vast majority are actually semi-monocoque. The Satellite was a true

monocoque design, meaning it was far simpler structurally than any

contemporary aircraft. This simplicity could result in an aircraft that

was cheap to produce and assemble, with far less to go wrong. These

traits were vital as the Satellite was intended to become a flying

Model-T Ford.

The

1948 Planet Satellite was an unusual and very beautiful aeroplane. Its

appearance suggested that Hergé had created it especially for Tintin to

steal. The aircraft was the shape of a tear-drop, with a butterfly

‘Y-shaped’ tail. Its ‘hygienically’ clean shape spoke of speed, progress

and a utopian future. The Satellite was a revolutionary design in

almost every way. It was a true monocoque design, for those unfamiliar

with the term- this does not mean it was single-penised (In fact, the

aircraft had no penis). A monocoque structure is supported by its

external skin, as opposed to using an internal frame. It is analogous to

an invertebrate (such as a beetle), whereas an animal with a normal

internal skeleton, like a person, is more like a traditional aircraft.

Though many aircraft are described as monocoque, strictly speaking the

vast majority are actually semi-monocoque. The Satellite was a true

monocoque design, meaning it was far simpler structurally than any

contemporary aircraft. This simplicity could result in an aircraft that

was cheap to produce and assemble, with far less to go wrong. These

traits were vital as the Satellite was intended to become a flying

Model-T Ford.Following World War Two, Major J. N. D. Heenan (more on him later) went to the United States to study the needs of the general aviation market. He concluded that what was needed was a cheap and quiet aircraft. By adopting the ‘pusher configuration’, with the engine (he would choose a 250-hp Gipsy Queen 32) and propeller behind the cabin, noise would be significantly reduced for the occupants. This layout would also give the pilot and passengers of the a four-seater an excellent, unobstructed view from the cockpit. Additionally it would make allow the nose section to be smooth and aerodynamically efficient.

There was a potentially huge market for the aircraft, notably in the US and Australia. If Planet Aircraft Ltd got it right, tens of thousands of aircraft would be produced and exported across the world.

Revolutionary design

The Satellite was immensely ambitious, embracing several untried (though extremely promising) technologies. The first hurdle was to master the monocoque. As no bracing members were present, the skin had to be strong enough to keep the fuselage rigid. To get this level of rigidity without the design becoming massively overweight required the use of unusual materials. Major J. N. D. Heenan, the maverick designer of the Satellite, thought the answer was to make it from magnesium (Magnesium-Zirconium to be precise, as Hergé’s Thomson and Thompson would say). The company Magnesium Elektron (ME) came onboard, funding the programme (the company still exists today and builds components for, among other things, the F-22’s gearbox). ME had received enormous orders during World War II, and had supplied 10,000 tons of the material in 1943. The post-war period was tough for ME and they were keen to diversify, Heenan seemed to be offering them an exciting avenue. The author approached Magnesium Elektron for information relating to the Satellite, the company declined to reply, we shall see why. ME was a subsidiary of Hughes & Co Ltd, a chemical and plastics company. In 1946 Hughes were bought by Distillers Company Ltd, a Scottish whisky and gin giant, and so the Satellite was to be funded by booze money.

At this time, most looked to aluminium as the primary aeronautical material, but some of the more maverick aircraft designers saw the potential of magnesium. These non-conformists also tended to put the propeller at the back in the ‘pusher configuration’. In 1943 Northrop flew the XP-56 ‘Black Bullet’, an aircraft seemingly from a parallel universe. This bat-winged fighter was an extremely unconventional design and like the later Satellite, was a ‘Magnesium pusher’. The XP-56 proved dangerous to fly, and delays in its testing meant it was still unready at a time when piston engined-fighters were yesterday’s technology. Somebody at Northrop clearly thought the XP-56 was not mad enough and began work on the wonderfully lunatic XP-79. The unlucky pilot would have to lie down as he controlled a rocket-propelled flying wing. If this was not dangerous enough he had to do this while manoeuvring his aircraft to slice enemy aircraft in half with its leading edges. Despite the benefits of magnesium (it is exceptionally light and strong) it had a reputation for bursting into flames and, if impure, to corrode easily. On its maiden flight on September 12th 1945, the XP-79 spun out of control after seven minutes of flight. Test pilot Harry Crosby bailed out, but was struck by the aircraft and was killed. Shortly afterwards the project was binned.

Click here for the story of Britain’s cancelled superfighter

A couple of months later, on 7 Nov 1945, Group Captain H. J. Wilson of the RAF was flying at over 600 mph in his Meteor F.Mk 4. This flight, which exceeded 606 mph, smashed the world air speed record and made a hero of Wilson. Though some Germans had flown faster in World War II, Wilson’s record was the first officially acknowledged speed record since 1939. Prior to the speed record Hugh ‘Willie’ Wilson had already led a very impressive career. He had been a leading test pilot. He had fought with the RAF’s crack No. 111 Squadron. His skills had been used to test fly captured German aircraft and he had almost been killed as he tried to land a Ju 88 that suffered engine failure on take-off. The speed record was merely the most conspicuous achievement for a man who did much to further the progress of aeronautical science. He then left this world of glory to become test pilot for the fledgling Planet Aircraft company and soon become managing director.

Clean sheet

The Satellite was built in the Robinson Redwing factory at Croydon, Purley Way, Surrey in 1947. Its name, like its appearance was bold and futuristic. It was not like any other aircraft. The July 15th 1948 issue of Flight found the design ‘startling’ and identified the reason for the designer’s unconventional approach,

“Major J. N. D. Heenan, of Heenan, Winn and Steel, consulting engineers, 29, Clarges Street, London, W.1, is the man responsible for the Satellite. It is the first aircraft which he has designed, but, as he himself says, had he ever designed an orthodox aircraft, preconceived ideas would have so trammelled his outlook that the concept of such a design as the Satellite would have been virtually impossible; an argument with which we are inclined to agree.” and further:

“ Beyond stating that the Satellite is so clean aerodynamically

that it almost justifies the term hygienic”

There was a certain genius to choosing a ‘virgin’ aircraft designer, free from conventional wisdom, but is this long-held view of Heenan correct? John Nelson Dundas Heenan is something of a mysterious character that history has largely forgotten. He appeared at, at least, one World One pilots reunion in the 1930s, though it is not believed he had flown in the Great War.

A trawl of patent records reveals he filed seventeen, most relating to heaters and boilers; one, somewhat bizarrely, relates to an improved golf club bag. The solitary patent relating to aircraft is from 1949 and describes a radical fuselage framework structure requiring far fewer parts than conventional designs. He was also actively interested in metallurgy from the 1930s.

The idea of Heenan being an aviation outsider is a myth; in fact Heenan was a vital part of the secret project which led to America’s first jet aircraft. Heenan was involved in the British Air Commission in World War II and communicated a vast amount of Frank Whittle’s reports on jet propulsion to USAAF Col D. J. Keirn. Keirn was the AAF Materiel Command project officer, in charge of bringing Britain’s advanced jet technology to the US. With this information America was able to build and fly its first jet, the P-59A in 1942.

Whisky business

The Satellite which was yet to fly, was displayed at the 1948 Farnborough. Among the thousands of of visitors attracted to the aircraft was a young Bill Gunston who wished he had enough money to buy one for himself. The prototype was taken to Redhill, an aerodrome used by Imperial airways in the 1930s in 1948. It received the registration G-ALOI in April 1949. The aircraft was ready for its first flight, at the able hands of Willie Wilson. He described this event to the Distiller’s Gazette, “After the first Hop which resulted in the undercarriage collapsing, the Air Registration Board called for an investigation into the stressing. After numerous delays the machine was prepared for a second hop to about 20 ft, then executed what I thought to be quite a reasonable landing. When, on inspection, it was found that the main keel had broken, that really brought the wrath of the ARB upon us, insisting that the aircraft had to be completely re-stressed…my own view was that we should, in the old phrase, ‘jack up the windscreen and run a new aeroplane underneath’, and I recommended to Distillers that they pack up the venture and sack H. J. Wilson. To give them their due they appreciated my endeavours and did very kindly offer me a job in one of their divisions; but I considered that the profession of flogging whisky was probably more dangerous than test flying!”

Click here for the story of Italy’s cancelled superfighter

So what had gone wrong? In designing the Satellite, Heenan had sent a wing section to the National Physical Laboratory for testing, as some believed magnesium had insufficient torsional strength. The results were very encouraging. The section withstood ten million deflection cycles at 10 per cent of the maximum bending load on the wing. When deflection was increased to 40 per cent a further two million cycles were experienced before failure occurred. Tragically the same tests had not been carried out on keel member and undercarriage points.

Click here for the story of Convair’s insane ring-wing fighter

An unlikely venture

Two Satellite prototypes were built, but the project was cancelled shortly afterwards. However, the story of this gin-funded, magnesium weirdo was not over. Major Heenan’s rich imagination bore an even more outlandish plan: In 1951 the Heenan, Winn and Steel company began converting the Satellite prototype G-ALXP into an experimental helicopter! Heenan had purchased the rights to a helicopter concept first developed by the American designer Fred Landgraf, creator of the Landgraf H-2. Unlike any other helicopter before or since the H-2 used a tension-rod drive system to drive side-by-side rotors. Pitch of the freely rotating blade shells was controlled by ailerons close to the tips of the rotors.

In 1952, Firth Helicopters started construction of what was now known as the Firth FH-01/4, but it proved to be a nightmare. Numerous problems dogged the project, which seemed impossible to solve given the small size of the company’s resources. The helicopter was cancelled before it had reached a flight-worthy stage. What did exist of the Firth FH-01/4 was presented to the College of Aeronautics at Cranfield in 1955. The story of the Satellite was now over, but its configuration would return.

Satellite of love

The Lear Fan was a product of love. When the aircraft’s creator Bill Lear died in 1978, his devoted wife Moya did all she could to see the project succeed. Bill Lear was a great innovator, his inventions included the 8-track tape and the Lear Jet. He also had a whimsical sense of humour, naming one of his daughters ‘Shanda’ (Shanda Lear!).

Moya was a former dancer, turned philanthropist and her father was the vaudeville genius John ‘Ole’ Olsen, creator of the broadway smash ‘Hellzapoppin’. As an aside, Moya and Bill’s son John Lear is one of the world’s most accomplished pilots and an ardent believer in the earthly presence of extraterrestrials.

Moya knew her late-husband’s design was a winner, and aggressively pursued investors.

In configuration, the gorgeous Lear Fan was reminiscent of the Satellite. It had the same pusher configuration, and the same Y-shaped tail. Like the Satellite it was innovative in its choice of construction and materials, and was one of the first aircraft to use large amounts of composite plastics.

The Lear Fan is officially recorded as making its first flight on the 32nd December 1980. The bizarre ‘date’ was an attempt to grant the project funding despite it technically being a day too late to be eligible. Like the Satellite, the Lear Fan was a case of too much too soon. It used two engines to power one propeller, making it as aerodynamically clean as a single-engined aircraft, but as reliable as a twin. The Federal Aviation Administration (the US organisation which ensures aircraft are safe), did not like this design as it put a lot of strain on the gearbox and would not give it their stamp of approval. The Lear Fan was abandoned in 1985, and Moya died in 2001.

So was this the end of the ‘Y- pusher’?

In 2001 a new age of aerial warfare began. The US invaded Afghanistan, and the drone became the symbol of war in the ‘Information Age’. Just four weeks into 2001, a sinister aircraft had taken its maiden flight, the General Atomics MQ-9 Reaper. The Reaper was the first of a new breed of remotely piloted combat air vehicles. That the Reaper chose a similar design solution to the Satellite, with a Y-shaped tail and pusher engine, is a vindication of Major Heenan and his visionary little aeroplane.The coming of the Reaper was going to be end of this story.

Until, I uncovered something very strange.

Shute and ask questions later

Neville Shute Norway was an aeronautical engineer and author of fiction when he joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve in World War II. Earlier, he had worked on the famous R.100 airship with Barnes Wallis, inventor of the bouncing bomb. In 1931 he set up the Airspeed Ltd aircraft company, along with A. H. Tiltman, a friend from the R.100 project. Thanks to his immensely creative thinking Norway ended up in what would become the Directorate of Miscellaneous Weapons Development. The madcap DMWD were encouraged to think outside the box in developing ways to counter Nazi Germany. Their hare-brained, yet often successful, schemes included coating the sea in coal dust so, from the air, it appeared to be land. Norway himself was involved in the development of the ‘The Great Panjandrum’ of 1943. This was an enormous set of rocket-propelled wheels, full of a ton of explosives designed to blow a tank-size hole through the German coastal defences. The Great Panjandrum, named for a character in nonsense poem, proved a surprising performer. It was described by Brian Johnson, for the BBC documentary Secret War,

“At first all went well. Panjandrum rolled into the sea and began to head for the shore, the Brass Hats watching through binoculars from the top of a pebble ridge…Then a clamp gave: first one, then two more rockets broke free: Panjandrum began to lurch ominously. It hit a line of small craters in the sand and began to turn to starboard, careering towards Klemantaski, who, viewing events through a telescopic lens, misjudged the distance and continued filming. Hearing the approaching roar he looked up from his viewfinder to see Panjandrum, shedding live rockets in all directions, heading straight for him. As he ran for his life, he glimpsed the assembled admirals and generals diving for cover behind the pebble ridge into barbed-wire entanglements. Panjandrum was now heading back to the sea but crashed on to the sand where it disintegrated in violent explosions, rockets tearing across the beach at great speed.”. The unlikeliness of this device has led some to conclude that this project’s primary objective was to distract German Intelligence from Britain’s real invasion-planning efforts.

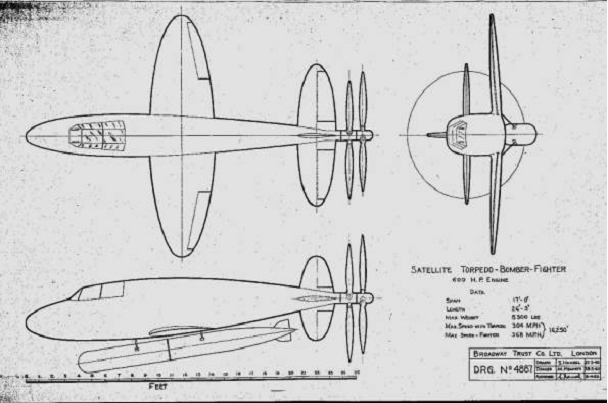

For Norway’s connection with the Satellite we need to delve further back, to his 1940 plan for a parasitical torpedo bomber. Buried away in a folder in Nuffield College Library, Oxford is a folder containing text, with accompanying diagrams and drawings. The documents describe a proposal for the construction in USA of ‘a large Amphibian Flying Boat, capable of carrying four “Satellite” planes, each capable of carrying its own 18″ torpedo or one 1500 lb. “Diving Bomb”‘. The typescript was originally contained in a plastic folder labelled ‘Burney Amphibian and Satellites’. The concept is from the mind of Neville Shute. What is striking is not just the name of the parasitical torpedo bombers, but the configuration- they are ‘pushers’, with an overall similar configuration to Heenan’s aircraft.

Could Heenan’s work in advanced projects at the British Air Commission have given him access to this project? It is certainly possible. If this is the case, then could it be Heenan’s naming of the aircraft was a wry reference to Shute’s secret torpedo bomber? The link is at best speculative, but there is another link between Heenan and Shute. Don Middleton, who until he passed away, was the leading authority on the Planet Satellite, was also an ex-Airspeed employee.

We will leave the last word on the Satellite to Wilson from the previously quoted interview in the DCL Gazette:

“The machine was probably the way ahead of its time, it was built in the wrong material, definitely understressed but otherwise possibly delightful…In case the Distillers should take the above as criticism,may I state that currently I am testing their Gordon’s gin and Black Label whisky, both of which I find handle extremely well and fully meet their advertised performance.”

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου