Chariot racing was massively popular in ancient Rome; so much so

that the world’s highest paid athlete and the first billionaire from

their ranks possibly pertained to one

Gaius Appuleius Diocles.

According to classical studies professor Peter Struck (at University of

Chicago), the ancient charioteer’s accumulated prize money equated to

35,863,120

sesterces, which is equivalent of around $15 billion or £9.6 billion. But while popular culture (including

Ben-Hur)

has presented the Roman penchant for brutal spectator sports, their

long-time ancient rivals were also interested in chariot races fueled by

skilled competitors and roaring crowds. We are obviously talking about

Carthage – with the Circus of Carthage being the largest sporting arena

outside Rome, built solely for such grand events. And now archaeologists

have come across an advanced technological ambit that rather

complemented the exhilaration of chariot races, and it entailed a nifty

liquid cooling system that aided both horses and chariots.

For long historians were puzzled by the ‘efficiency’ of chariots

(relating to both the horses and the vehicle) in Carthage, since the

city-state was located in North Africa, traditionally known for its hot

and arid climate. Simply put, even horses could have fainted mid-race in

such rigorous conditions. But as a result of a recent excavation at the

site of Circus of Carthage, experts have now identified the use of a

special water resistant mortar in one of the structures of the stadium.

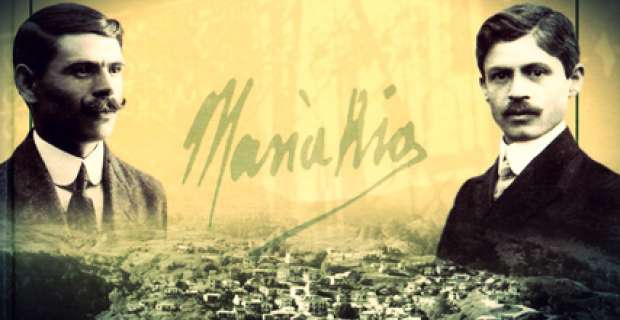

Πρωτοπόρος

κινηματογραφιστής και φωτογράφος στο χώρο των Βαλκανίων ο Μίλτος

Μανάκης, γεννήθηκε στις 9 Σεπτεμβρίου του 1882 στο βλάχικο χωριό Αβδέλα

Γρεβενών. Με το φακό του κατέγραψε πολύ σημαντικές στιγμές στην περίοδο

των έντονων κοινωνικοπολιτικών αλλαγών στα Βαλκάνια.

Πρωτοπόρος

κινηματογραφιστής και φωτογράφος στο χώρο των Βαλκανίων ο Μίλτος

Μανάκης, γεννήθηκε στις 9 Σεπτεμβρίου του 1882 στο βλάχικο χωριό Αβδέλα

Γρεβενών. Με το φακό του κατέγραψε πολύ σημαντικές στιγμές στην περίοδο

των έντονων κοινωνικοπολιτικών αλλαγών στα Βαλκάνια.