During WWII, Irena Sendlerowa, a Catholic Polish social worker, saved 2,500 Jewish children from death. That’s more than Oscar Schindler managed with 1,200. Though recognized by Yad Vashem in 1965 as being one of the Righteous Among the Nations (a non-Jew who saved Jews during the Holocaust), the rest of the world knew virtually nothing about her.

At least, until 1999 when students at a rural Kansas high school were looking for material for their school play. Thanks to them, Sendlerowa was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize but lost it to Al Gore.

Sendlerowa was born on 15 February 1910 in the town of Otwock. Her father was a doctor whose motto was, “jump into the water to save someone drowning, whether or not you can swim.” He did just that, which was why he was the only doctor in Otwock who’d treat Jews.

When Germany invaded Poland in 1939, Sendlerowa was among those responsible for the state-run canteens. These provided the city’s poor, elderly, and orphaned with food, clothing, and financial aid. In the early weeks of the German occupation, Jews who went to these canteens got something extra: false documents to help them pass off as Catholic.

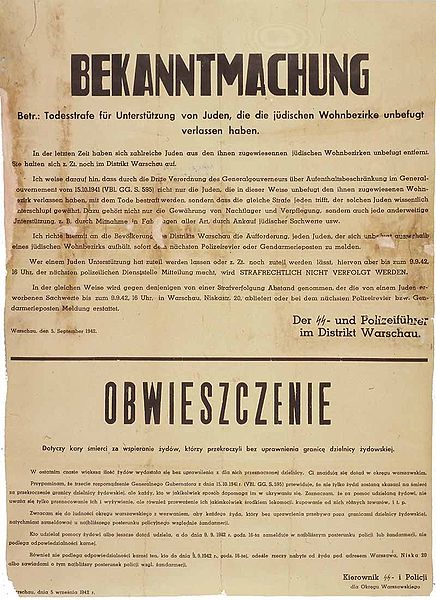

This ended in 1941 when helping a Jew became a crime punishable by death, a sentence that was extended to the entire family. Of all the countries under German occupation, Poland was the only one in which such a stiff penalty was imposed. For Sendlerowa, it made no difference because of what she saw the previous year.

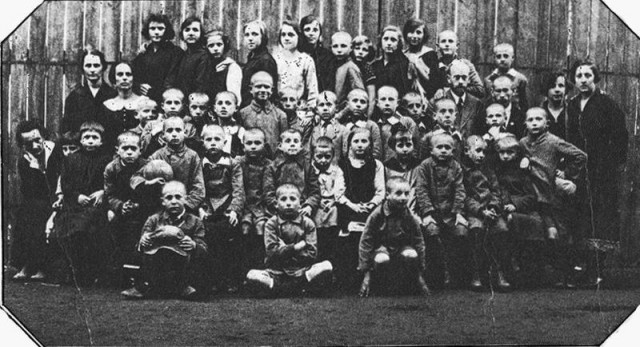

A number of the German soldiers recognized their childhood hero when they came to collect the 192 or 196 children under his care. Since some prominent Jews with international reputations were spared death, Korczak could have saved himself. But he refused, insisting that he accompany his charges to Treblinka.

Sendlerowa saw them all that day – the children dressed in their best, some with small, handmade dolls in their hands. She also saw Korczak’s face and understood she’d never see any of them ever again. That’s when she decided to take up his legacy by joining Zegota; a Polish resistance movement also called the Council to Aid Jews. Sendlerowa was assigned to its children’s section and sent to the Warsaw Ghetto.

SHARES

| FacebookTwitter |

Sendlerowa’s job was to oversee hygiene, but she couldn’t resist wearing a Star of David armband to annoy the guards and to show her solidarity with the Jews. She also brought a dog along with her, one specially trained to bark on command.

Once inside, she and other colleagues did what they could to convince parents to hand their babies and toddlers over to them. Then they snuck them out in suitcases, medical bags, ambulances, and carts. These would often be sedated, but Sendlerowa took no chances.

It couldn’t last, of course. On 20 October 1943, someone reported her to the Gestapo. Sendlerowa was arrested and interrogated but refused to name her co-workers or give details on the Zegota. So they tortured her. When that failed, the broke her legs and feet.

Still, she wouldn’t reveal a thing, so they ordered her executed, but the Zegota bribed her guards, and she escaped and she went into hiding for a while. Recovering quickly, she returned to Warsaw under a false identity and worked as a nurse in a public hospital where she managed to hide five more Jews.

When Israel recognized what she had done in 1965, Poland refused to let her leave to receive the award. They only let her do so in 1983. Her son Andrzej died on 23 September 1999, the very day that students at Uniontown High School in Kansas found a small news clipping about her.

There wasn’t much info, but the students were fascinated. They chased down other leads and made a play based on her story called “Life in a Jar.” Then in February 2000, they found out she was still alive, so they got in touch and sent her a translated copy of their manuscript.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου