Even when Latin gave way to Greek, the Byzantines still considered themselves Roman. In the early medieval period, the Byzantines reclaimed control of many of the fallen territories, notably the Italian peninsula. They fought various emerging powers and faced several attempts to take their triple walled capital city. The only time it had been taken was through internal strife and treachery coinciding with the Fourth Crusade.

The walls of the great city had never been breached by a foreign foe. For more info about the walls of Constantinople click here, for more on past sieges, click here.

A more sophisticated threat by this time, the Bulgarian Empire, and the Serbian Empires fought against the Byzantines as well. The city itself was greatly weakened by the Black Death and a large earthquake as well as civil wars that divided the populace. Under the Palaiologoi dynasty established after the reclamation of Constantinople, the empire became a shadow of its former self while a new eastern power set its sights on the great city.

The Ottoman Turks came to power with the downfall of the Seljuk Turks. Starting from a small state in Turkey, the Ottomans came to dominate the other states in the area and began to grow. By the 15th century, the Ottomans had claimed all of the Byzantine territories in Turkey with the exception of a narrow territory of the Empire of Trebizond, an allied successor state.

The Turks had also crossed the Bosporus and taken all of the Thracian territory west of Constantinople leaving control over a few square miles west of the city to the Byzantines. Even the great Byzantine city of Thessaloniki, which had once been considered as the new capital by Constantine, was taken by the Ottomans by 1430. The Byzantines had resorted to paying tribute to the Ottomans and at times acted as an extension of the Ottomans.

The Ottomans brought their own cannons, but these were still early cannons that proved ineffective against the strong Theodosian walls. The Ottomans were eventually forced to withdraw as they found no way to gain access to the city and Byzantine leaders were able to successfully incite a rebellion within Ottoman territory.

The Byzantine empire was in tatters, and the population continued to shrink, but the last remnants of the Romans stumbled on. In 1448, the last Roman/Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI, ascended to the throne. He resolved to stand up to the Ottomans, and when a young and ambitious Mehmet II took the Ottoman throne in 1451, the two leaders would fight with everything they possessed.

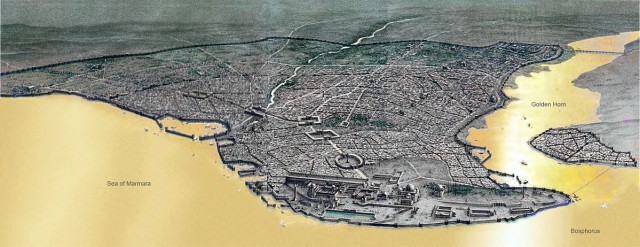

Mehmet II had a grand strategic vision that was dependent on securing Constantinople for use as a new imperial capital. Mehmet was twenty-one when he ascended the throne and had spent his life learning how to rule. His approach for the capture of the city was similar to the previous Arab attempts; he secured and fortified areas around Constantinople to cut supplies to the city. The twin fortresses of Rumelihisari and Anadoluhisarı were completed on either side of the Bosporus just miles north of Constantinople.

Mehmet started his campaign by building his army up near Adrianople. He employed the services of a talented cannon designer known as Orban, who spent months designing and casting some of the largest cannons in the world at the time. Mehmet II spent the time waiting for the cannons by incessantly planning out ways to actually take the city. Mehmet II was truly prepared to take the city and arrived at the gates with an estimated 80-100,000 infantry, 90 ships and 70 cannons of varying calibers.

The total number of men defending the city numbered around 8-10,000 including a large combination of European allies who had finally realized that they would much rather have the Byzantines at their borders than the Turks. Constantine XI also ensured that the walls were in pristine condition and raised the chain across the golden horn. In the early days of April, Mehmet arranged his forces around the city and by the seventh of April 1453, the full-scale siege of the city began.

The Ottomans set up their cannons across from the very middle of the Theodosian walls located along the westernmost hill. A few days into the siege the cannons were able to destroy the tower of St. Romanos along the main wall. Constantine was shaken enough by this to seek peace with Mehmet in exchange for vast tribute payments to the Sultan. Mehmet offered to let Constantine leave the city and rule the Peloponnese of Greece while Mehmet would peacefully occupy the city. Constantine adamantly refused to leave the city, and the two sides resolved to fight to the end.

The Turkish navy attempted to fight their way into the Golden Horn. However, they were thwarted by the great chain, and the Byzantines were able to destroy a large portion of the Navy with cannon fire from the ships in the harbor and the sea walls along the Horn. The Turks were able to pay back the Byzantine navy however when Mehmet ordered his men to transport several of his ships overland from the Bosporus to the Golden Horn to bypass the chain.

Though the cannons of the Turks were superior at the time, the Byzantines still were able to cause significant casualties with their cannons. When a breach was opened in the walls and the Turkish infantry rushed through the defenders aimed into the masses and fired their cannons, which were packed with multiple shots each the size of a walnut.

This primitive shotgun devastated each wave of Turkish attacks and forced Mehmet to devise other methods of attack. Though several breaches were opened in the walls, they proved ineffective as the walls were quickly repaired with barrels of earth which actually absorbed the cannons better than the walls did. Even if the enemy attacked before repairs could be made the gap between the inner and outer wall forced any attackers to be flanked on three sides while still being subjected to missile fire from the main wall.

The exhausted defenders were forced to spread their force across more than twelve miles of walls. Mehmet did send his ships to attack the walls along with the land infantry, but the ships were easily repulsed. The land assault was where the Ottomans finally won the day, however. Tens of thousands of soldiers rushed the walls with scaling ladders.

Initially, the defenders were able to hold the Ottomans at bay under the superb leadership of the Venetian Giovanni Giustiniani, who had been placed in charge of the defense of the Theodosian walls since his arrival. During the assault, however, he was struck by a shot that pierced his arm and chest, and he was carried through the gates and back to the Venetian ships in the harbor. When the defenders saw their leader fall, their morale dropped and the last wave of Ottomans, the Janissaries, were able to overcome the defenders and scale the walls.

The city was looted for three days although fortunately did not endure the same level of death and destruction that was inflicted by the fourth crusade. Though it cost him dearly in both men and money, Mehmet was able to have his dream realized and after establishing Constantinople/Istanbul as the capital, the Ottoman Empire flourished for hundreds of years.

The walls were an inspiration for early European kingdoms and when they finally fell they served as a lesson for all subsequent city defenses. The city had long protected Christian Europe from Muslim expansion and its fall ultimately left Europe vulnerable to attack from one of history’s greatest Muslim powers.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου