The

United States has decided: with 306 electoral votes, Joe Biden is

officially the 46th U.S. president. Biden’s victory has been considered a

turning point for a number of policy issues, from the tackling of the

COVID-19 pandemic to racial injustice, and it raises important questions

about the future of the U.S. foreign policy. In the face of four years

of isolationism where the U.S. found itself during Trump’s presidency,

Biden’s geopolitical strategy promises to be more internationalist, with

a greater consideration for multilateral agreements and international

organizations. A greater focus on climate, environment and NATO is

expected. In this context, the recovery of relations with the old

continent will certainly be one of the foreign policy priorities. As for

relations with China, the main dossiers will probably concern human

rights, Taiwan and Hong Kong. The president-elect may also be willing to

defuse tensions with Iran, reducing the sanctions against Tehran and

reviving the nuclear deal.

The

United States has decided: with 306 electoral votes, Joe Biden is

officially the 46th U.S. president. Biden’s victory has been considered a

turning point for a number of policy issues, from the tackling of the

COVID-19 pandemic to racial injustice, and it raises important questions

about the future of the U.S. foreign policy. In the face of four years

of isolationism where the U.S. found itself during Trump’s presidency,

Biden’s geopolitical strategy promises to be more internationalist, with

a greater consideration for multilateral agreements and international

organizations. A greater focus on climate, environment and NATO is

expected. In this context, the recovery of relations with the old

continent will certainly be one of the foreign policy priorities. As for

relations with China, the main dossiers will probably concern human

rights, Taiwan and Hong Kong. The president-elect may also be willing to

defuse tensions with Iran, reducing the sanctions against Tehran and

reviving the nuclear deal.

As for the Middle East, however, it seems that Biden’s line will not differ from Trump’s: the withdrawal of troops from Iraq and Afghanistan will continue to be a priority, with the aim of putting an end to the “forever wars” affecting the region- even though the fact that this happens in conjunction with the achievement of autonomy over oil speaks volumes about U.S. interests in the fight against terrorism. Regarding the Israeli-Palestinian question, Biden’s position is very clear, and again does not differ much from the policies implemented by the former administration. His almost 40-year old friendship with Netanyahu, Israel’s Prime Minister, and his lack of intentions to move the U.S. embassy back to Tel Aviv make it difficult to reverse the destructive cut-off of diplomatic ties with the Palestinian Authority that occurred under the Trump presidency. The distinctive feature of the new administration is Biden’s commitment to restore the financial aid to the Palestinian people, and his advocacy for a termination of Israel’s settlement activities in the occupied Palestinian territories.

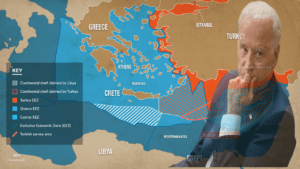

The already strained relations between Turkey and Greece may exacerbate following Biden’s election to the White House. Biden, former vice president of the United States during Obama’s mandate, gained a deep knowledge on the Eastern Mediterranean following his longtime membership in the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee, and appears to be determined to strengthen the U.S. alliance with its traditional allies. The newly elected president has already proven in the past to be inclined to pursue a more resolute policy towards Turkey than his predecessor, and his history provides some indicators of how he could deal with the Aegean dispute.

Following the discovery of a natural gas field in the exclusive economic zone of Israel by the Texan company Noble Energy in 2009, several Eastern Mediterranean countries started drilling their respective continental platforms in search of more energy fields. However, the lack of delimitation of their EEZs by some countries has sparked strong tensions regarding energy explorations in the region, which may be carried out into disputed areas. This is the case of the ongoing controversy between Turkey and Greece. Turkey, which has not signed the International Convention on the Law of the Seas, does not recognize islands as having the right to their own exclusive economic zone, and has sent the Oruç Reis to explore near Kastellorizo, a Greek island of only 12 sq.km. located 2 km off the Turkish coast and 600 km off the Greek mainland. This move immediately triggered sharp reactions from Athens and other European countries, urging Erdoğan to stop operations in disputed areas and resuming dialogue for a peaceful resolution of the controversy.

During Trump’s presidency, the United States did not pursue a distinctly proactive agenda in the Eastern Mediterranean, aiming instead at easing e existing tensions between countries in order to create a situation of stability that would allow the U.S. to expand its energy markets. While it is undeniable that relations between Greece and the United States have never been as close as in recent years, it is also true that, despite some disagreements, Trump and Erdoğan have established a calm relation between their respective countries. In particular, Trump’s decision not to impose sanctions on Ankara following Turkey’s S-400 missile deal with Russia avoided what could have turned into a tightening of relations between the two countries. In addition, the recent U.S. military disengagement from the Middle East has granted Turkey a wider scope for action, allowing it to carry out its planned operations with more freedom, especially in Syria and in Libya, other than in the Southern Caucasus. It follows that, for the White House, an excessive imbalance towards one of the parties in the Aegean dispute would have been likely to lead to complications, while indeed it has always avoided exposing itself excessively by siding with one or the other actor. However, the lack of assertive politics in the Eastern Mediterranean does not mean that Trump has left everything to chance: on the contrary, it mirrors a diplomatic move intended to improve U.S. position in the region without necessarily assuming the leadership, as it was used to do in the past.

Biden’s approach to Erdoğan will probably differ. The former has made no secret of his criticism against the latter, labelling him “an autocrat” and advocating for the support of opposition leaders, and has criticized the Turkish president for his attacks on freedom of expression. Moreover, he has repeatedly taken a pro-Kurdish stance in the past, which led the Turkish government to consider him as “anti-Turkish”. Biden’s criticism has also been addressed towards Erdoğan’s foreign policy in the Eastern Mediterranean. He has condemned Turkey’s threats of violence against Greece while stating that “disputes in the region must be resolved peacefully and the sovereignty and territorial integrity of all countries must be respected and protected”, and he has reaffirmed the need to impose sanctions on Turkey to prevent it from expanding its belligerent posturing fueled by the “Blue Homeland” conceptualizations. If the U.S. intransigence towards Turkey were to increase hardly, the strengthening of the Ankara-Moscow axis and further distancing of Turkey from its Western allies could materialize, as had already happened during the Obama presidency, with possible disastrous effects on the stability of the region.

However, no clear-cut alignment with Greece is expected, nor a drastic change of strategy, at least in the short term. Ankara remains a partner of extreme strategic importance, and the interests at stakes are considerable. For this reason, it is unlikely that the United States will start an open confrontation with a key NATO ally. “It is typical that rhetoric dominates an election race. But afterward facts on the ground will take prominence”, Vice President of Turkey Fuat Oktay stated in this regard. In addition, there are vital domestic factors that the new U.S. administration will likely have to devote much of its attention to, including the fight against COVID-19.

In conclusion, we can expect that, during Biden’s presidency, the knots that have plagued the U.S.-Turkish relation in recent years will be brought to surface, and Ankara may be in the position to face some challenges with Washington. Biden’s pre-election rhetoric suggests the adoption of a confrontational approach to his Turkish counterpart, which would not benefit the stability of the Eastern Mediterranean. Nonetheless, there will probably be some institutional pressures to moderate the hot spirits of Biden’s administration in favor of maintaining at least a decent relation with a fundamental ally, who could otherwise take other decisive steps in the direction of the Russian domain at any moment.

Simona Scotti

About The Author

Simona Scotti

Intern

Simona Scotti is a senior student at Ca’ Foscari University of Venice, majoring in International Relations. She has received two scholarships to carry out her studies in Belgrade and in Bogotá, studying respectively Security Studies and Political Science. She has volunteered in Azerbaijan for two months at the International Eurasia Press Fund and got educated also in Russia. Simona`s academic focus lies on post-Soviet states, Western Balkans, Latin America and international law.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου