?

από anixneuseis

Source: Getty

In April 2015, Carnegie Europe published an article that

analyzed the global footprint of the EU. Looking at the period of the

second European Commission of former president José Manuel Barroso,

which ran from February 2010 to October 2014, the article examined how

the union deployed different foreign policy instruments across the

world. Now, at the beginning of a new institutional cycle, this article

examines developments during the commission of Jean-Claude Juncker, who

was president from November 2014 to November 2019.

As

in 2015, the present analysis combines traditional tools of EU

diplomacy and various forms of operational engagement (see figure 1).

Diplomacy includes visits by the EU’s top leaders, declarations by the

union’s high representative for foreign affairs and security policy, and

conclusions of the European Council and the Council of Ministers.

Engagement comprises sanctions, civilian and military operations, EU

assistance, and trade. The article also looks at the sizes of the

union’s overseas delegations and the deployment of EU special

representatives.1

These

indicators cover only a small part of the EU’s international

activities. Multilateral diplomacy, for instance, forms a large part of

the union’s external action but cannot be easily quantified. The article

does not deal with the many types of structured dialogue that the EU

entertains with countries across the world or with its diverse

non-trade-related economic activities. The development of other EU

instruments, such as recent initiatives to strengthen military

cooperation and crisis-response capacity or the 2016 global strategy, go

beyond the scope of this study. Still, this analysis offers a clear

indication of which countries were the focus of the EU’s attention and

where the union engaged operationally.

CHANGE AND CONTINUITY IN EU FOREIGN POLICY

The

EU’s foreign policy agenda has changed considerably over the past ten

years. At the time of the second Barroso commission, the focus was

clearly on the Arab Spring uprisings that began in late 2010, Russia’s

2014 annexation of Crimea and the war in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas

region, relations between Kosovo and Serbia, and Iran’s nuclear program.

The Juncker commission also had to deal with many of these topics, but

it faced a broader agenda arising from the disruptive policies of the

administration of U.S. President Donald Trump and the need to respond to

the rise of China. The massive flows of refugees and migrants that

peaked in 2015–2016 became another dominant subject of EU external

policy.

There

were important institutional differences, too. In 2010–2014, much time

and energy was absorbed by implementing the foreign policy reforms of

the EU’s 2009 Lisbon Treaty, which established the EU’s current legal

framework. In particular, the treaty set up the European External Action

Service (EEAS), the union’s foreign policy arm. By 2014–2019, then EU

high representative for foreign affairs and security policy Federica

Mogherini had more opportunities to spend time outside Brussels.

The

rising dominance of the European Council, which brings together EU

heads of state and government, in the field of foreign policy became

more apparent under the 2014–2019 presidency of Donald Tusk. He showed a

greater interest in international developments than had his

predecessor, former European Council president Herman van Rompuy. This

shift limited the capacity for initiatives from the high representative

and the EU’s Foreign Affairs Council, which gathers national foreign

ministers.

The

cohesion of the EU member states suffered, particularly in 2014–2019,

from the divisions and mistrust left by the financial and migration

crises. It became increasingly difficult to achieve the unanimity needed

to make decisions on foreign policy. And the UK’s 2016 referendum to

leave the EU amounted to a severe setback that weakened the union’s

position both regionally and globally.

Despite

these differences, the two periods also show a good deal of continuity.

The overall level of international engagement remained roughly the

same. The number of visits of the EU’s top leaders declined, as did the

number of declarations by the high representative. By contrast, the

European Council and the Foreign Affairs Council adopted significantly

more conclusions on foreign affairs. The number of countries under EU

sanctions stayed about the same. Financial assistance and the sizes of

EU delegations increased moderately.

In

marked contrast to the emphasis on enhancing military cooperation in

the EU’s work in 2014–2019, the union launched only three new operations

in this period, and the overall number of deployed military and police

personnel declined. Trade policy was more dynamic, with the adoption of

six new trade agreements and the start of a number of new trade talks.

Altogether, while external policy went through interesting conceptual

innovations between 2014 and 2019, the data do not indicate significant

progress in operational terms.

Just

as in 2010–2014, EU trade policy emerged as the only instrument with a

truly global reach in 2014–2019. Assistance and sanctions again covered

all regions of the world, but with a clear emphasis on neighboring

regions and sub-Saharan Africa. (Unless otherwise stated, “neighboring

regions” in this article include countries in the EU’s Eastern and

Southern neighborhoods, Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway, Russia,

Switzerland, Turkey, and the Western Balkans.) This regional focus was

even more evident in all the other instruments analyzed.

However,

all indicators measuring the EU’s attention to foreign policy topics—in

particular, travel by top officials, declarations by the high

representative, and council conclusions—reveal a relative decline in the

emphasis on neighboring regions (see figure 2). Instead, the union paid

more attention to sub-Saharan Africa and Central and South America.

The

authors’ telephone conversations with practitioners in March 2020

indicated three main explanations for this shift from a regional to a

global orientation.

First,

the conflicts in Ukraine, Syria, and Libya all erupted during the

second Barroso commission. EU institutions and officials initially

followed the unfolding drama on a daily basis and tried—not very

successfully—to contribute to political solutions. By the time of the

Juncker commission, these three conflicts had turned into permanent

crises. They still received significant attention, but much less than

before, leaving more space for issues beyond the EU’s neighborhood.

Second,

Mogherini had a more global outlook than her predecessor, Catherine

Ashton. Mogherini traveled more widely and engaged with regions that had

hardly been on the EU’s radar. This found expression in the high

representative’s declarations and in council conclusions.

Third,

the prominence of the migration challenge in recent years explains the

union’s increased attention on Africa. The numbers of visits,

declarations, and conclusions, as well as the level of EU assistance to

the continent, rose significantly.

VISITS OF THE EU’S TOP OFFICIALS

The

top institutional actors of EU external policy are the president of the

European Commission, the president of the European Council, and the EU

high representative for foreign affairs and security policy. They

interact with their international counterparts in different ways: over

the phone, by receiving visitors and convening conferences in Brussels,

and by visiting foreign capitals. As they are busy people and

international travel is costly and time consuming, their trips are a

useful indicator of the priorities of EU foreign policy.

The

total number of visits by Juncker, Tusk, and Mogherini in 2014–2019,

which includes their participation in multilateral summits, fell

slightly on 2010–2014 (see figure 3). This is mainly because Juncker—in

stark contrast to his predecessor, Barroso—traveled very little beyond

the EU’s borders.

As

in the earlier period, the data confirm the EU’s strong relationship

with the United States, with forty-one visits—although this number

includes trips to the UN headquarters in New York. Japan was the second

most visited country, probably because of negotiations on the EU-Japan Economic Partnership Agreement.

Russia, which was in second place in the previous period, saw a

radical decrease in its number of visits—down to two from eighteen in

2010–2014. This fall is due to the EU’s sanctions against Russia following

the Ukraine crisis that began in late 2013. By contrast, the EU

leaders’ eleven visits to Ukraine testify to the union’s strong

engagement to help this country.

Turkey,

a crucial and difficult counterpart on both the Syria crisis and

migration issues, was visited thirteen times. Egypt remained the most

visited country in North Africa, but with significantly fewer trips

after President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi came to power in June 2014: ten in

2014–2019 compared with seventeen in 2010–2014. A similar pattern can be

observed with Israel and Palestine, which together were visited only

six times, as opposed to twenty in the preceding period. This reflects a

tense relationship between the EU institutions and Israel and the

continuing deadlock in the Middle East peace process. In the Western

Balkans, EU visits remained frequent, with Serbia, Kosovo, and North

Macedonia the preferred destinations.

In

terms of regional distribution, travel to countries in the EU’s

neighborhood accounted for 44 percent of total travel—a reduction from

over half in 2010–2014. Asia was the second most popular destination

region, representing almost 20 percent of total visits, but with fewer

trips than in the previous period. By contrast, EU officials traveled

more often to sub-Saharan Africa (twenty-five visits) and to Canada

(eight).

DECLARATIONS OF THE HIGH REPRESENTATIVE

During

Ashton’s tenure, declarations of the high representative were the EU’s

preferred way to communicate about international developments. Ashton’s

successor, Mogherini, also used this instrument frequently—917 times—but

significantly less often. That reflects a greater engagement not only

with the mainstream media but also with social media, particularly

Twitter and Facebook. For this study, the authors analyzed declarations

of the high representative from November 2014 to November 2019 and

statements from EEAS spokespeople and press releases that contained

quotes by the high representative.

Declarations

can have great political importance when they define the EU’s initial

response to an emerging crisis or unexpected development, but many

simply rehash established EU positions. Three-quarters of Mogherini’s

declarations referred to developments in specific countries, while

one-fourth cited international negotiations or conferences or annual

recurrences, such as Human Rights Day or International Anticorruption

Day.

The

high representative adopts declarations on their own authority, but

they have to be careful to remain in the framework of the EU’s consensus

on each issue. The radical decline in the number of declarations on

Syria and Libya compared with the previous period probably reflects the

fact that these topics were controversial among EU member states.

Despite

this decrease, Syria, the Middle East peace process, Turkey, Ukraine,

and Libya continued to be among the most recurrent topics in the high

representative’s declarations. But a comparison with the earlier period

indicates that the EU’s focus gradually shifted away from these regions

(see Figure 4). Venezuela was mentioned the second most often in

2014–2019, with overall references to the Americas up to 12 percent of

the total from 4 percent in the previous period. Declarations on

sub-Saharan African countries increased from 14 percent to 22 percent.

Developments in Asia accounted for 12 percent, a share similar to that

recorded during Ashton’s tenure.

Altogether,

references to events in the EU’s neighboring regions amounted to only

40 percent of all high representative declarations in 2014–2019, against

more than 55 percent in 2010–2014.

CONCLUSIONS OF THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL AND THE FOREIGN AFFAIRS COUNCIL

Like

the declarations of the high representative, the conclusions of the

European Council and the Foreign Affairs Council reflect the EU’s

positions on international events. The main difference lies in the fact

that conclusions are negotiated among all member states, usually in a

complicated process that involves several layers of preparatory bodies.

As they represent the collective views of the EU members, conclusions

have greater political weight than declarations. For this study, the

authors tracked the numbers of references to non-EU countries in the

conclusions of meetings of the European Council and of the Foreign

Affairs Council from November 2014 to November 2019.

In

the EU’s current legal framework, established in 2009 by the Lisbon

Treaty, the European Council is the union’s top foreign policy body.

During the Juncker commission, it met twenty-one times. EU foreign

ministers normally come together as the Foreign Affairs Council once a

month, although other meetings are held if the situation requires it. In

2014–2019, the council met seventy-four times.

The

conclusions of the European Council and the Foreign Affairs Council

contained 463 references to non-EU countries in 2014–2019. This was a

significant increase on the previous period, when 279 references were

recorded, which is quite surprising given that the number of meetings

remained roughly the same. One explanation might be that Mogherini, as

chair of the Foreign Affairs Council, was particularly averse to

controversial debates in the council and therefore put a large number of

more consensual topics on the agenda. The fact that in the preceding

period the European Council had less time for foreign policy, because it

focused almost exclusively on the financial crisis, could also have

played a role.

The

data show that migration, developments in Syria and Libya, and

terrorism in the Levant were among the top preoccupations of EU

governments, featuring eighty-seven times in total. The crisis in

Ukraine was mentioned twenty-six times (see figure 5). Overall, almost

45 percent of the conclusions concerned events in a neighboring region:

as with the high representative’s declarations, this marks a reduction

from 55 percent in 2010–2014.

Asia

and Latin America received considerably more attention from the EU than

in the earlier period, with Venezuela (twelve mentions) and North Korea

(eleven) particularly in the spotlight. References to sub-Saharan

African states also increased significantly, accounting for 20 percent

of the total.

The

conclusions show the emergence of new issues, too. Brexit was one of

the most frequently mentioned topics after the 2016 UK referendum, as

was climate change before and after the United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change’s 2016 Paris Agreement to reduce greenhouse

gas emissions.

INSTRUMENTS OF DIRECT ENGAGEMENT

Important

types of direct engagement by the EU include sanctions, civilian and

military operations, the deployment of special representatives,

development assistance, and trade.

SANCTIONS

Sanctions

have become the EU’s primary hard-power instrument, even though they

have an uneven record of effectiveness in changing the behavior of the

targeted state. Most frequently, the EU adopts arms embargoes against

states involved in military conflicts and imposes visa bans and asset

freezes on governments responsible for human rights violations. In a few

instances, such as with Iran, Russia, and Syria, the EU has established

comprehensive sanctions regimes that also target the financial and

energy sectors. In past years, the EU’s sanctions policies have been

closely coordinated with those of the United States. This cooperation

has diminished during the Trump administration.

As

of January 2020, thirty-three states were subject to some kind of EU

sanctions, as opposed to thirty at the end of the union’s previous

institutional cycle in 2014. During the term of the Juncker Commission

new sanctions were imposed on Burundi, Mali, Nicaragua, Turkey,

Venezuela, and Yemen. Sanctions against Eritrea, Ivory Coast, and

Liberia were lifted.

In

geographic terms, sanctions clearly represent an area where EU action

has global reach. However, here too, there is an emphasis on sub-Saharan

Africa, the Middle East, Eastern Europe, and the Western Balkans.

CIVILIAN AND MILITARY OPERATIONS

Since the European Security and Defense Policy became operational in 2002, the EU has undertaken thirty-five civilian and military missions. Most of them have been relatively small in scale and of limited ambition.

Growing

instability in the EU’s neighborhood has reignited the union’s interest

in military cooperation. Particularly under the Juncker commission, the

EU launched many initiatives to boost capabilities and enhance

cooperation in this area, with the aim of achieving strategic autonomy.

But considerable progress in the development of policy has not yet led

to the launch of more ambitious operations.

As of January 2020, seventeen missions were ongoing and approximately 5,000 personnel were deployed. Compared to 2015,

this is approximately the same number of missions, but the number of

deployed personnel decreased from 6,000 in 2015. While nine missions

were initiated under Ashton, only three started under Mogherini.

Of the seventeen missions active in January 2020, eleven were

civilian, mostly police and rule-of-law operations. Of the six military

missions, one—in Bosnia and Herzegovina—served peacekeeping purposes;

three—in the Central African Republic, Mali, and Somalia—were training

missions; and two were naval missions. The Somalia mission, Operation

Atalanta, aimed at combating piracy off the Horn of Africa, while the

naval mission Operation Sophia sought to identify, capture, and dispose

of vessels used by migrant smugglers or traffickers in the

Mediterranean.

The

distribution of these operations demonstrates the particular focus of

EU foreign and security policy on the neighborhood and Africa. Seventeen

of the thirty-five ongoing or completed operations have taken place in

African states, with most of the rest occurring in the Western Balkans,

Eastern Europe, or the Middle East.

EU SPECIAL REPRESENTATIVES

The

appointment of EU special representatives is another tool of direct

engagement with certain regions or on certain policy priorities. The EU

has appointed sixteen special representatives since 1999 (see table).

Since 2009, they have been nominated by the European Council on a

proposal from the high representative.

There

is an ongoing debate between the EEAS and the member states about

whether EU special representatives should be seen as instruments

primarily of the high representative or of the member states. This

dispute is probably the reason why so few of them have been appointed in

recent years. By contrast, other major international actors, such as

the United States or the UN, have many such senior envoys.

The

distribution once again demonstrates a focus on Africa and the EU’s

neighborhood. Five of the sixteen special representatives have dealt

with Africa-related issues; six with countries in Eastern Europe and the

Western Balkans; and three with the Middle East.

DEVELOPMENT ASSISTANCE

The

EU, with its member states, is the world’s largest donor of development

assistance. Under the union’s 2014–2020 budget, the collective

development assistance spending of the EU institutions amounted to

approximately €14 billion ($15 billion) a year. This figure is projected

to increase in the 2021–2027 budget, which is under negotiation as of

this writing. The European Commission has proposed a 30 percent increase

in funding for EU external action, but many member states take a more restrictive approach.

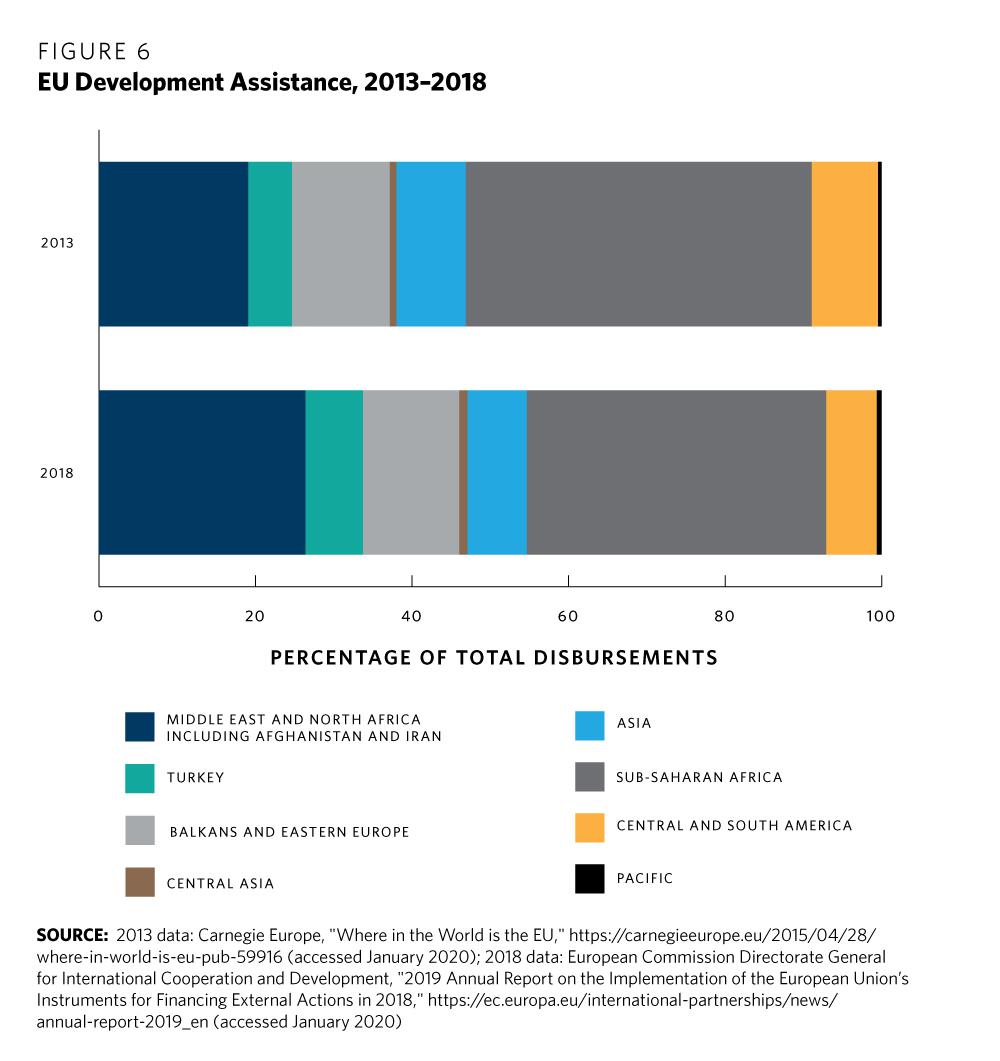

In

2018, the latest year for which data are available, almost 40 percent

of total spending went to sub-Saharan Africa (see figure 6). This was

followed by the Middle East (26 percent) and the Western Balkans and

Eastern Europe (12 percent).

If

per capita spending is considered, and countries with extremely small

populations are ignored to avoid distorted results, the West Bank and

Gaza Strip, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Georgia had the

highest concentrations of EU assistance in 2018. Altogether, the level

of EU aid on a per capita basis is significantly higher for the union’s

neighboring regions than for other parts of the world.

TRADE AGREEMENTS

The EU is the world’s biggest trading power, accounting for approximately 17 percent of global trade in goods and services in 2018. External trade in goods and services represented

about 35 percent of the EU’s gross domestic product in 2018. Trade is

an area in which the EU speaks with one voice because the union’s Common

Commercial Policy empowers the commission to negotiate trade

agreements, monitor their implementation, and respond to unfair trade

practices. On trade, the EU is a genuine global actor: it either has

concluded or is planning to conclude trade agreements with most

countries of the world.

Trade

policy used to be a matter for technocrats but achieved a high

political profile during the years of the Juncker commission. First, the

proposed Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership between the EU

and the United States and the EU-Canada Comprehensive Economic and Trade

Agreement ran into massive public protests. Then, the entry into force of the EU Association Agreement with Ukraine was delayed when the Netherlands voted against it in a referendum in April 2016.

One

might have expected widespread public resistance to further trade

liberalization to dampen the EU’s appetite for new agreements. But

aggressive U.S. trade policies under the Trump administration, together

with a crisis of the multilateral trade system centered on the World

Trade Organization, prompted the EU to maintain its efforts to negotiate

trade agreements with countries and regions across the world. The

Juncker commission concluded six such accords, with Canada, Japan,

Mexico, Singapore, southern African countries, and Vietnam. Twelve new

trade negotiations were initiated during this time, the same number as

in the preceding period.

SIZE OF EU DELEGATIONS

As

of December 2019, the EU had 141 delegations around the world employing

5,799 staffers, including officials of the EEAS and the European

Commission and local agents. Before the Lisbon Treaty reforms, this

network essentially dealt with trade and development assistance. Since

2009, the EU delegations have expanded their role and are now the main

interlocutors between the union and the host states, including on

political matters. More recently, the EU has also sent military attachés

and antiterrorism experts to join the delegations.

The

political importance of the union’s relationship with a country is one

of the main factors behind the size of a delegation. Beijing and

Washington, for example, host large EU missions with close to 100

officials. By contrast, the deterioration of relations with Russia has

resulted in a reduction of the size of the EU delegation in Moscow by

almost a third.

A

second factor is the level of EU assistance to the host country. About

two-thirds of the staff in the delegations are commission officials,

most of whom work on assistance projects. Turkey—where political

importance and a huge assistance program come together—hosted in

December 2019 the largest EU delegation, with 175 staffers. That is a 25

percent increase on the level in December 2013, mainly because of the

massive expansion of assistance after the EU and Turkey reached a deal in March 2016 aimed at discouraging refugees from entering the EU.

Overall,

the geographic distribution of the delegations follows that of

development aid: 25 percent of EU staff abroad are deployed in

delegations in the union’s neighboring regions; 35 percent are in

sub-Saharan Africa.

Notable

changes in 2014–2019 included the doubling in size of the EU

delegations to Jordan and Lebanon in response to crises in the Middle

East and the steady growth of staff in sub-Saharan Africa.

CONCLUSION

Analysis

of the EU’s use of external policy instruments confirms that the union

is a global actor in some respects, such as trade policy, sanctions, and

assistance, but that it focuses its engagement mainly on neighboring

regions. This regional bias also applies to the indicators of the EU’s

attention to international developments: visits, declarations, and

council conclusions. Yet in recent years, the union has shown an

increased interest in sub-Saharan Africa and, to a more limited extent,

other parts of the world.

The

comparison between the second Barroso commission and the Juncker

commission indicates that the EU’s overall level of engagement with the

outside world has remained roughly the same. In general, the union’s

regional and global reach did not grow significantly between 2014 and

2019. At a time when Europe’s weight on the global scales was

diminishing and its neighborhood was troubled by multiple crises, the EU

and its member states were not able or willing to invest significantly

more in their common foreign policy.

The

new EU leadership team that came into office in November 2019

understands that the present state of EU external policy leaves room for

improvement. The leaders started with high ambitions: senior

politicians such as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen

and High Representative Josep Borrell declared that Europe would

finally learn the “language of power,” turn itself into a geopolitical actor,

and take the lead on critical policy issues such as climate, cyber, and

Africa. But as the new top officials were about to begin their work,

Europe was hit by the coronavirus pandemic, which is likely to be a game

changer for EU foreign policy.

Francesco Siccardi is a senior program manager at Carnegie Europe.

The authors are grateful to Emma Murphy, Nicola Paccamiccio, and Malte Peters for their research support.

NOTES

1 Data

for this article come from the European Commission, the European

External Action Service, and the EU Council General Secretariat.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου