A Nazi Gone Rogue

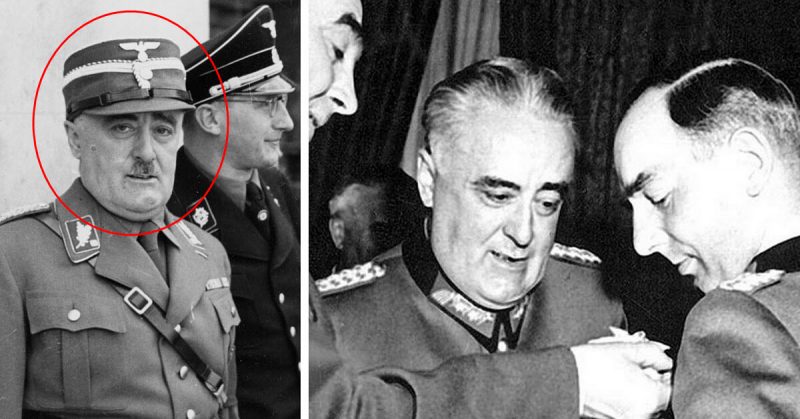

Of course, as an esteemed member of the Nazi Party entrusted with a prominent position, it would seem that Glaise-Horstenau could enact the changes he so desperately needed in Croatia. Yet Glaise-Horstenau was unable to open a single Nazi official’s eyes to the horrors happening in Ustaše-controlled Croatia – and with concentration and death camps scattered throughout Germany’s territories, these atrocities were just a few among many more.The violence was all part of Hitler’s master plan; Glaise-Horstenau was unaware of his party’s true intentions. Once he discovered that the Nazi Party and its leaders weren’t going to end the crimes they were committing in any camp, in any city, he began plotting to fight back against these unforgivable atrocities.

In 1944, Glaise-Horstenau decided to end the crimes occurring in Croatia by joining the effort to overthrow Pavelić and his regime. This secret plan, named the Lorković-Vokić plot, was developed by Croatia’s Minister of Interior Mladen Lorković and Minister of Armed Forces Ante Vokić. Lorković and Vokić hoped to stop aligning Croatia with the Axis powers; they wanted to force Pavelić and his government out and replace it with one that supported the Allies.

Glaise-Horstenau joined the Lorković-Vokić plot efforts, becoming deeply involved. Yet the Lorković-Vokić plot failed, and those associated with the attempted rebellion were executed. Fortunately, Glaise-Horstenau escaped such a fate – but the Croatian government and Nazi Party didn’t overlook his involvement in the plot.

Unsurprisingly, Pavelić wanted him removed from office to ensure no further attacks towards Pavelić’s dictatorship could occur. In September 1944, Pavelić joined forces with Siegfried Kasche, a German ambassador. Together, the two worked within the Nazi Party to get Glaise-Horstenau removed from office – and the plan worked perfectly.

Within two weeks, the Germans announced that Glaise-Horstenau was no longer Plenipotentiary General. This single act of “firing” Glaise-Horstenau allowed the Nazis to fully take control of Croatia, and the Party took total control over the nation’s military forces within the following months.

Suddenly jobless, Glaise-Horstenau didn’t denounce the Nazi Party or Germany’s control over European nations. Instead, he remained closely tied to both the nation and its political party. He was given a job in the Führer-Reserve, a special program designed for high-ranking military officers awaiting new assignments, and worked as the Military Historian of the South East. It was in this uneventful, action-free job that Glaise-Horstenau finished the final days of his military career.

The Allied Forces Arrive

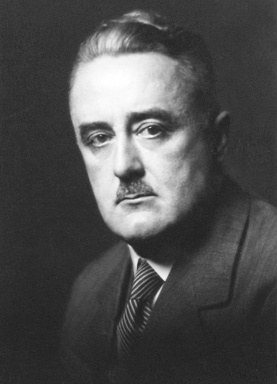

On May 5, 1945, Glaise-Horstenau no longer needed to worry about his temporary job within the Nazi Party. On that day, the U.S. Army arrived and took Glaise-Horstenau captive. An almost lifelong supporter of Nazi Germany, he was terrified that the U.S. Army would send him to Yugoslavia – and even more worried that he would be tortured and killed there.Within two months of his capture by the Allied forces, Glaise-Horstenau took his fate into his own hands and committed suicide on July 20, 1946, while held captive at Langwasser military camp.

Though he was never able to explain what, exactly he’d tried to fight against in Croatia to the Allied forces, the unfinished autobiography Glaise-Horstenau left behind did the speaking for him. Filled with details previously unknown to those beyond Croatian borders and free from its dictator’s rule, the stories and images Edmund Glaise-Horstenau left behind illustrate so clearly his distaste for the cruelty – and paint a picture of his fight against Nazi Germany and the cruelty it enacted in its reign of terror.

It’s thanks to the words and descriptions of Glaise-Horstenau that we today know what it was like to suffer at the hands of the Axis powers, and just how cruel those in charge became. From the detailed reports he sent the OKW in the first years of his role as Plenipotentiary General to the reflections and images he shared in the pages of his unpublished autobiography, Edmund Glaise-Horstenau allowed the world beyond Nazi Germany and its territories to experience what he did.

Though he supported the Party for much of his life, Glaise-Horstenau was willing to risk his safety and face the same fate as many others persecuted by Nazi Germany if he could end the reign of terror in Croatia – and although he didn’t succeed during his lifetime, his words and reports still make a difference in history.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου