1. Frederick the Great

Prussian ruler Frederick the Great is rightly remembered as a daring, ambitious commander and a smart innovator. But he was also a leader who showed little regard for the lives of his men. Over the course of the Seven Years War, Prussia suffered 180,000 deaths in its armed forces, a staggering amount for any army in the 18th century, and especially for the smallest population participating in the war.

2. Napoleon

The only 18th-century general more famous than Frederick, Napoleon Bonaparte began his career with careful manoeuvring and cunning tactics, using his intelligence to defeat numerically superior foes. But over time, the war-weary emperor seemed to lose his edge, and his later battles were often marred by a tendency to throw men into the meat grinder in hopes of winning through sheer brute force.

The turning point came in around 1807. At Heilsberg that year, he attacked the Russians with wave after wave of men, not adapting to the challenge of the situation. Two years later at Wagram, he turned General MacDonald’s corps into a human battering ram 8,000 strong that suffered terrible casualties failing to break through the Austrian lines.

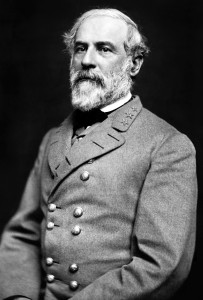

3 Robert E. Lee

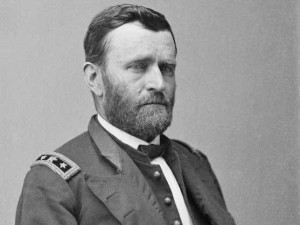

4 Ulysses S. Grant

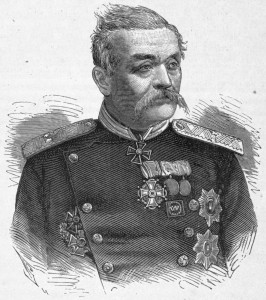

5 Generals Krüdener and Shakofsky

35,000 men were flung into a frontal attack against the defences skilfully assembled by Turkish General Osman Pasha. The Russian generals might have known what sort of trouble they were heading into if they had taken the time to do reconnaissance on the Turkish positions. Instead, they hurled their soldiers into endless assaults, losing 7,300 men in just one day, and a further 20,000 over the following three weeks.

6 General Nogi

Launching an assault on the 19th of August 1904, Nogi began throwing thousands of men against Port Arthur’s defences. But what he thought were glass windowed houses on the edge of the city turned out to be concrete and steel fortifications. Nogi had been told that 10,000 lives would be a small price to pay for Port Arthur, a chilling figure in itself. This single failed assault led to 16,000 casualties for no gain.

7 A. G. Hunter-Weston

This comment by First World War British General Hunter-Weston exemplifies his attitude towards the men serving under him. A charming and rotund man, he must have seemed at first glance like jolly company. But in the theatre of war, he was willing to endorse senseless butchery.

Hunter-Weston became the most infamous British commander of the 1915 Gallipoli campaign, an expedition notorious for slaughter and incompetence. Obsessed with full frontal daylight attacks, he got thousands of men slaughtered. When confronted with the commander of a brigade which had just lost 1,300 men, he expressed pleasure at the fact that they had “blooded the pups”.

8 Douglas Haig

General Douglas Haig was not alone in being responsible, but his name is rightly associated with some of the most disastrous practices. Haig repeatedly tried to use tactics that had been shown not to work – particularly trying to destroy barbed wire with shelling and then sending waves of men in direct frontal assaults on enemy trenches.

Having failed spectacularly with these tactics at the Somme in 1916, Haig, replicated them at Passchendaele in 1917, where he made things worse with a preliminary bombardment of carefully drained ground that turned it into a muddy quagmire in which 90 men a month drowned while thousands more were gunned down as they struggled to advance.

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου