That same saga came to a sudden end in 1307, two centuries later. As the sun rose over Paris on Friday the 13th of November, the doom of the Knights Templar was sealed.

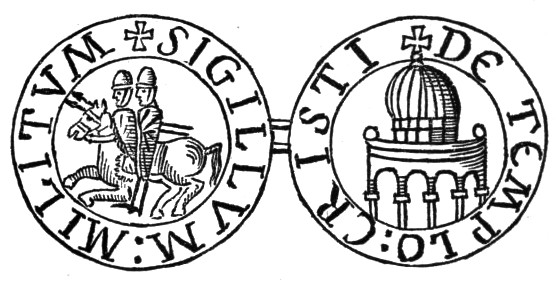

The new order was given a headquarters on the Temple Mount, within the royal palace itself. From this location, they derived their name – The Poor Knights of Christ and the Temple of Solomon.

Just as their name soon morphed to become the simpler “Knights Templar”, so too did the order itself develop and evolve. With enthusiastic backing from the Church, their ranks grew almost as quickly as their finances improved, and they were soon one of the most favoured charities in Christendom.

Being regularly gifted with money and soldiers was a huge advantage, but the order also began receiving the ownership of many businesses, giving them a more permanent source of income. In the years that followed, their business ventures grew in size and prosperity, while their many chapter houses formed the foundation of early European banking.

On top of the considerable wealth, the support of the Church was especially useful in 1139, when the Pope actually raised the knights above the law entirely. Although they were still subordinate to the Papacy, the Knights Templar could now move unhindered across borders, a law unto themselves.

SHARES

| FacebookTwitter |

Of course, their rise to power shocked and unsettled many of the longstanding nobility in Europe. Even as their military power in the Middle East began to fade in the late 13th Century, their influence in Europe only grew. As many of the royal families in Europe were now in debt to the Templar Order, their power was truly unrivalled.

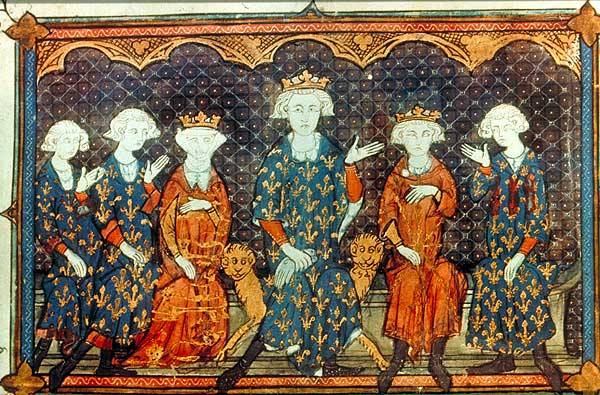

One monarch who had been loaned particularly large sums of money by the Knights Templar was King Philip IV of France. Not only had his war with England forced him into serious debt but his attempts to depose the previous Pope had been thwarted by the very Order which had loaned him his money. The Knights Templar had humiliated him, and even after that he still owed them huge sums of capital.

So it was that, at dawn on Friday the 13th of November 1307, warrants of arrest were issued for all principle members of the Knights Templar. The key figures of the order were in Paris to discuss the possibility of merging with another Crusader faction – the Hospitallers – and it was the perfect time for Philip to strike.

Philip had nothing but lies to offer as evidence against the knights.

Not that it mattered, of course.

Many of the knights were held in captivity for years, often in solitary confinement. Under torture, most of the Templars – including the Grand Master himself – admitted to the charges. However, they did so expecting that the Pope would eventually proclaim them innocent, and exonerate the order. Instead, they were sentenced to spend the rest of their lives in prison.

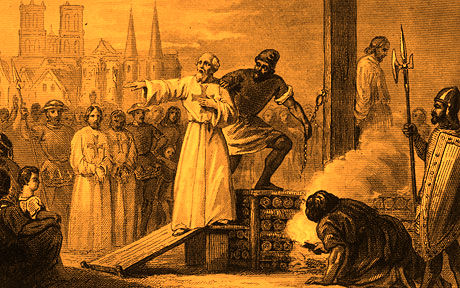

That night, on the 18th of March 1314, the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar burned at the stake.

Once they had proclaimed themselves The Poor Knights and numbered less than a dozen men. At their peak, they rose above the law and moved freely through Europe, a state within each state, an empire without borders. In their downfall, the same economic might that propelled them to power led to their end.

In the history of medieval Europe, there are few stories as intriguing and, ultimately, as tragic as the rise and fall of the Knights Templar.

Main image by Daniel VILLAFRUELA, CC BY-SA 4.0 & Les Still, mysticrealms.org.uk CC BY-SA 3.0 / Wikipedia

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου