On October 28th, 1940, fascist Italy launched an unprovoked and ultimately disastrous attack on Greece which signaled it’s entry in World War Two.

On April 6th, 1941, Nazi Germany started their offensive against Greece.

Its strongest part extended over a distance of 200 kilometers (125 miles) from the mouth of the Nestos River to the point where the Yugoslav, Bulgarian, and Greek borders meet.

The German plan of attack was based on the premise that, because of the diversion created by the campaign in Albania, the Greeks would lack sufficient manpower to defend their borders with Yugoslavia and Bulgaria.

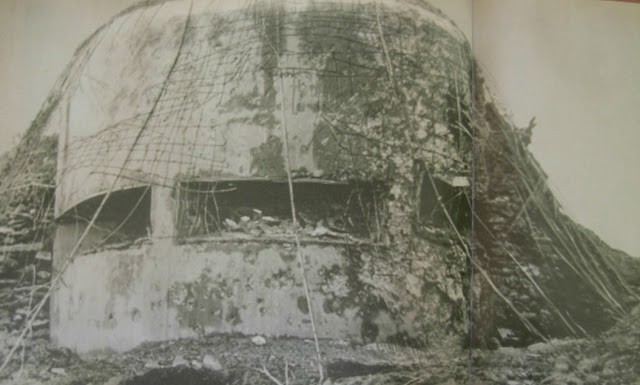

After a three-day struggle, during which the Germans massed artillery and dive bombers, the Metaxas Line was finally penetrated.

Some of the fortresses of the line held out for days after the German attack divisions had bypassed them and could not be reduced until heavy guns were brought up.

The main credit for this achievement must be given to the 6th Mountain Division, which crossed a 7,000-foot snow-covered mountain range and broke through at a point that had been considered inaccessible by the Greeks.

By driving armored wedges through the weakest links in the defense chain, the freedom of maneuver necessary for thrusting deep into enemy territory could be gained more easily than by moving up the armor only after the infantry had forced its way through the mountain valleys and defiles.

Once the weak defense system of southern Yugoslavia had been overrun by German armor, the relatively strong Metaxas Line, whicl1 obstructed a rapid invasion of Greece from Bulgaria, could be outflanked by highly mobile forces thrusting southward from Yugoslavia. Possession of Monastir and the Vardar Valley leading to Salonika was essential to such an outflanking maneuver.

German troops invaded through Bulgaria, creating a second front. Greece had already received a small though inadequate reinforcement from British Empire Forces, in anticipation of the German attack but no more help was sent after the invasion began.

The Greek army found itself outnumbered in its effort to defend against both Italian and German troops.

When German troops officially entered Bulgaria during the first four days of March, the British reacted promptly by embarking an expeditionary force in Alexandria.

Several squadrons of the Royal Air Force as well as antiaircraft units had been operating in Greece during the previous months.

On the contrary, Greek leaders had repeatedly expressed their intention to defend themselves against any German invasion, no matter whether they would be assisted by their ally or not.

In a report Mr. Eden and his military advisers sent to London at the beginning of March, they summed up the situation by stating that there was a “reasonable fighting chance” and, with a certain amount of luck, a good opportunity “of perhaps seriously upsetting the German plans.”

When this hope finally and somewhat unexpectedly materialized at the end of March, the three countries failed to establish a unified command. No such initiative was taken, and there was only one meeting of British, Yugoslav, and Greek military representatives on 3 April.

By 12 April, the Yugoslavs were to concentrate four divisions along the northern border of Albania and provide additional forces in support of a Greek offensive in southern Albania.

The course of events demonstrated only too clearly how unrealistic these offensive plans were at a time when both countries should have attempted to coordinate their defense efforts against the German threat.

To enter northern Greece, the attacker had to cross the Rhodope Mountains, where only a few passes and river valleys permitted the passage of major military units.

Two invasion routes led across the passes west of Kyustendil along the Yugoslav-Bulgarian border and another one through the Strimon Valley in the south.

The very steep mountain roads with their numerous turns could not be negotiated by heavy vehicles until German engineer troops had widened them by blasting the rocks. Off the roads only infantry and pack animals could pass through the terrain.

Along the Yugoslav-Greek border, there is another mountain range with only two major defiles, one leading from Monastir to Florina, the other along the Vardar River.

Aside from these mountain ranges bordering Greece in the north, an aggressor must surmount a number of other alpine and subalpine mountain ranges barring access to the interior of the country.

Finally, the inaccessible Peloponnesus Mountains hamper military operations in the southern provinces of Greece.

Troops are subjected to extreme physical hardships by a campaign across Greece because habitations are few, water is in short supply, and the weather is inclement with sudden drops in temperature.

Following the entry of German forces into Bulgaria, most of the Greek troops were evacuated from western Thrace, which was defended by the Evros Brigade, a unit consisting of three border guard battalions, when the Germans launched their attack.

The 19th Motorized Infantry Division was in reserve south of Lake Doirani. Including the fortress garrisons in the Metaxas Line and some border guard companies, the total strength of the Greek forces defending the Bulgarian border was roughly 70,000 men. They were under the command of the Greek Second Army with headquarters in the vicinity of Salonika.

The Greek forces in central Macedonia consisted of the 12th Infantry Division, which held the southern part of the Vermion position, and the 20th Infantry Division in the northern sector up to the Yugoslav border. On 28 March, both divisions were brought under the command of General Wilson.

As a result, it was planned that the mobile elements of the XL Panzer Corps would thrust across the Yugoslav border and capture Skoplje, thereby cutting the rail and highway communications between Yugoslavia and Greece. Possession of this strategic point would be decisive for the course of the entire campaign.

From Skoplje the bulk of the Panzer Corps was to pivot southward to Monastir and launch an immediate attack across the Greek border against the enemy positions established on both sides of Florina. Other armored elements were to drive westward and make contact with the Italians along the Albanian border.

The XVIII Mountain Corps was to concentrate its two mountain divisions on the west wing, make a surprise thrust across the Greek border, and force the Rupel Gorge. The 2d Panzer Division was to cross Yugoslav territory, follow the course of the Strimon upstream, turn southward, and drive toward Salonika.

The XXX Infantry Corps was to reach the Aegean coast by the shortest route and attack from the east those fortifications of the Metaxas Line that were situated behind the Nestos.

All three corps were to converge on Salonika. After the capture of that main city, three panzer and two mountain divisions were to be made available for the follow-up thrusts toward Athens and the Peloponnesus.

Twelfth Army headquarters was to coordinate the initially divergent thrusts across southern Yugoslavia and through Bulgaria into Greece and, during the second phase of the campaign, drive toward Athens regardless of what happened on the Italian front in Albania.

This plan of operations with far-reaching objectives was obviously influenced by the German experience during the French campaign.

It was based on the assumption that Yugoslav resistance in front of the XL Panzer Corps would crumble within a short time under the impact of the German assault.

The motorized elements would then continue their drive and, taking advantage of their high degree of mobility, would thrust across the wide gap between the Greek First and Second Armies long before the Greek command had time to regroup its forces.

The other XVIII Mountain Corps units advanced step by step under great hardship. Each individual group of fortifications had to be reduced by a combination of frontal and enveloping attacks with strong tactical air support.

To be continued…

Many thanks to Pierre Kosmidis / pierrekosmidis.blogspot.gr

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου