SHARES

| FacebookTwitter |

On 15 October 1962, President Kennedy went ballistic at the discovery that the Soviets were trying to balance out NATO by building a nuclear missile site in Cuba. The Cuban Missile Crisis began the next day, ending 13 days later to a collective sigh of relief. Everyone believed that nuclear annihilation had been averted through diplomatic means.

But it’s actually Deputy Commander Vasili Alexandrovich Arkhipov we have to thank.

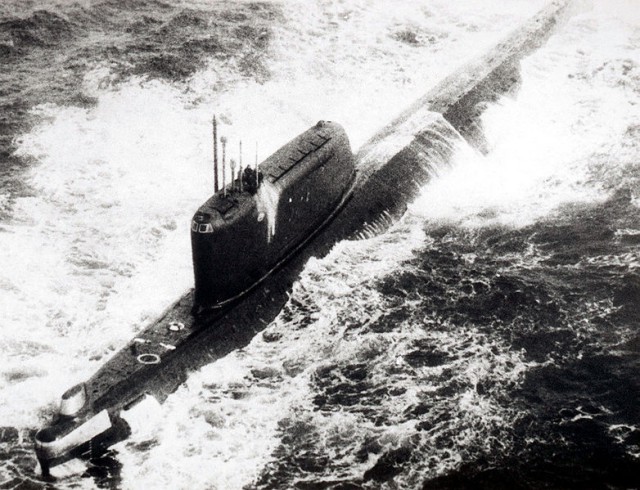

Fast forward to 1 October 1962. Four Foxtrot submarines armed with nuclear missiles are ordered to leave their Arctic base and head to Cuba. Each has its own captain, but all submit to the authority of their flotilla commander, Arkhipov.

He’s on the flagship B-59 acting as its second-in-command to Captain Valentin Grigorievitch Savitsky. Trailing him are a B-4, a B-36, and a B-130. All are diesel-powered because of the K-19 disaster. While fine in the Arctic, they become saunas in the tropical waters of the Caribbean which they reach on October 14, the day Tropical Storm Ella hits.

The next day, Moscow orders them to leave Cuban waters and head east to the Sargasso Sea. That same day, Kennedy announces the quarantine of Cuba and raises the country’s defense readiness condition (DEFCON) from 4 to 3 (in readiness for war), a first in its history.

Since no more messages arrive from Moscow, the submarine fleet relies on American radio broadcasts for information. They hear about an US invasion of Cuba, the launch of US warships and planes, and the possibility of Soviet submarines in the area.

Not able to stock up in Cuba, the men are on water rations limited to one glass per man a day. The coolest part of their submarine is in the front and rear, so each man is allotted some time in those sections to keep from fainting.

Between 4 and 5 PM, the USS Cony finds them. More US planes and ships make their way to the area, but are under strict orders not to attack.

To ease tensions, Kennedy calls Kruschev and tells him about the discovery. He assures the Soviet Premier that the US military will only force the fleet to the surface and will not engage them. He falsely assumes that Moscow has been in regular contact with them.

And still no word from Moscow.

Getting impatient, the US Navy begins dumping depth charges into the water, hoping that this more persuasive approach will work. They’re expecting a flare being fired from the Soviet submarine, because that’s what American subs do to signal an enemy of their desire to surface.

According to Soviet protocol, however, they must drop three charges and wait for a response to prove they’re willing to accept a peaceful surrender. And since the US Navy is dropping far more than that and without pause, Savitsky believes that outright war has begun.

By now, temperatures in the sub exceed 120° and the batteries are about to go out. If they don’t act soon, they’ll suffocate.

But Moscow remains silent.

Arkhipov and Savitsky get into an argument. Arkhipov considers the possibility that the Americans only want them to surface. Savitsky is convinced that war has begun and that Russia’s honor depends on him firing back.

But Arkhipov is still haunted by the deaths aboard the K-19. He saw first-hand the horrors that nuclear radiation can unleash. And he has a family back in Russia.

He stands his ground, Savitsky eventually backs off, and they contact the Americans who give them permission to surface.

In the 13 October 2002 edition of the Boston Globe, Thomas Blanton, director of the National Security Archive, was quoted as saying that some “guy called Vasili Arkhipov saved the world.”

And that’s why you’re able to read this.

www.warhistoryonline.com

Δεν υπάρχουν σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου